‘Does it not?’ cried Lady Whicher.

‘Not a bit. Its value comes from its unaltered chemical makeup.’

‘Ambergris or Mr Savage’s poetry?’ demanded Blakeney.

‘Precisely!’ I interposed, and just like that I was again on top. I attempted to thank my fair saviour, but the words transmuted by some reverse alchemy into an attack on Pendergast and his countess.

I will not bore you with the continuation of our match, as it proceeded through the duration of the second and most of the third course. I won in the end, but the victory was hollow to me — the entire episode was nothing but a cover to hide the fact that I could not speak to the woman beside me.

It was Vivien who at last broke the silence between us, and so I may say without hesitation that the fault for my current predicament lies squarely upon her shoulders. Had she not said anything I would not have been able to, and would have returned home to Pocklington Place that evening with a feeling of cowardice and self-reproach which would have lasted for a day or a week and then given way to my accustomed cheer.*

Instead, I left that evening with a wife.

I do not mean literally, of course — our courtship, while brief, was not that brief. But later when Simmons asked how the dinner had gone, I believe my words to him were, ‘I have found a wife, and I haven’t the least intention of letting her go.’

Bitterest of ironies! If I could return to that night in March and relive it, I should have eaten my foie gras with relish, taunted Pendergast with pleasure, and never spared a second glance at that awful creature on my left. Could I even return as a spirit and whisper in my own corporeal ear, I should whisper with such urgency, ‘Ignore her, sir! She will be your death!’

Well, but I cannot and I did not. Instead, when over the oysters she enquired, ‘What are your thoughts on the matter, Mr Savage?’ I turned and lost myself in those damned eyes and knew I was finished and did not mind a jot.

I will not here recount my wooing. It was, looking back, strangely joyous and brings me pain to recollect. There was throughout it a bizarre sense of burning happiness — a prickly feeling on the back of my neck, a pleasant tightness of the chest: something more than contentment, greater than the satisfaction of a match well made.

I thought it was the sensation of being in love. I have learned that it was not, it was the joy of the chase. I wonder now if I oughtn’t have been a hunter. Perhaps I still could be one. I am certain that Simmons keeps an ancient musket somewhere, and I could steal a horse from my coachman and sally forth to murder foxes — or stow aboard an Arctic vessel and try my hand at clubbing seals, which cannot be difficult. But that is neither here nor there. I am a poet, I am a married man, and I am resolved upon my own immediate suicide — for I married for money instead of love, and when I did I discovered that I could no longer write.

Two In Which My Sister Returns from School for Reasons Best Omitted, & I Am Forced to Deliver to Her a Previously Unmentioned Piece of Intelligence

I sit trying to write. I cannot. I have written no poetry in my six months of marriage. I have written drivel, doggerel, detritus, but nothing worthy of Calliope’s mantle.*

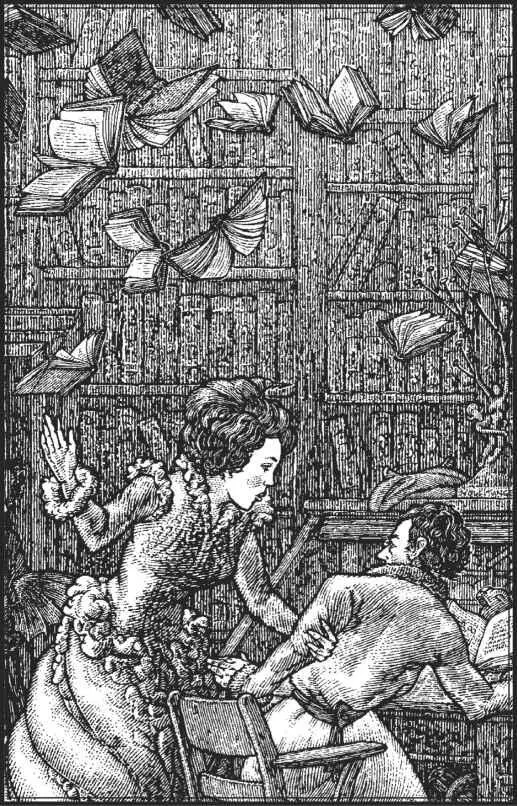

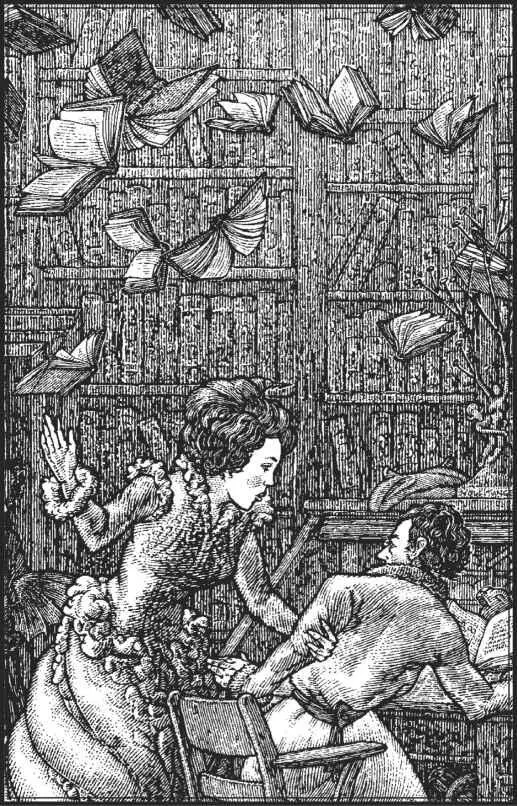

I sit at my desk in my study in my house which is called Pocklington Place which is in a nice part of London with which you are almost certainly familiar and so I shall not name for I do not like callers. My desk is mahogany and very large. It once belonged to an earl, but he was a wretched poet and so he died and now it is mine.* That is called justice, and I would there were more of it in this world. My study is large, as it is also my library. My library used to be upstairs, but it became apparent that I should spend my life walking up and down the stairs between my library and my study unless drastic action were taken. So I called in an architect who called in several workmen who charged me a prodigious amount of money, and I bid them remove the floor of my library — though I might equally have said the ceiling of my study, for they were one and the same (the one being directly below the other). They did this, with much banging and sawing and hammering, and they put in several very tall sliding ladders so that I could reach my books, and a very grand spiral staircase made of wrought iron which leads to a sort of balcony ringing the room on what used to be the floor of the library and the ceiling of the study, and where there are a few armchairs. When the workmen left, I had the grand, two-storey study in which is the mahogany desk at which I now sit trying vainly to write.

If you have ever written, you will know that it is either an arduous business or a simple one, but rarely in between. For me it used to be the one but is now the other. (I trust that you know which I mean when.)

I rise. I tear my hair and gnash my teeth. I chew the sleeves of my smoking jacket, which is red velvet and threadbare and which once I believed to be lucky but do not any longer. The words will not come.

‘Simmons!’ I call.

I am pacing, which is a habit of mine when I am agitated.

‘Simmons!’ I yell again. ‘Simmons, where are you? I am agitated!’

I pace my way to the door and wrench it open to call down the hallway, but he is standing there already. Which is a habit of his.

‘I’ve decided to kill myself, Simmons.’ I have been considering it for some months, but I have been putting it off because the weather has been fair. It is now foul, and still I cannot write, and it is time to do what must be done.

‘Very good, sir,’ says he. He is a good butler. ‘Might one ask how?’

I am moderately taken aback. In all my months of contemplation the question has never occurred to me. It is a good one, I reflect. ‘Don’t know,’ I say. ‘Hadn’t thought. I suppose I’ll just shoot myself.’

Those who are not well acquainted with Simmons say that he has no expression in either his face or voice, but I have known him these very many years and know better — and right now he looks pained.

‘Oh sir ,’ he says. ‘Begging your pardon, but who do you imagine would have to clean up the brains or the heart fluid or what have you?’

‘Who?’ I ask, wondering if there is a special branch of the public works committee one calls in such instances.*

‘Me,’ he says. Apparently not.*

‘I see. I’m sorry, Simmons. That was inconsiderate of me. I apologise.’ Firearms, clearly, will not do.

‘Think nothing of it, sir,’ he rejoins handsomely. He truly is a paragon.

I am now confronted with the reality of my situation. Somehow it had never seemed so real before; but when faced with the notion of poor Simmons scrubbing my brains off the bookshelves, my mind protests. But I am no coward. I plunge forward. I ask him if he has any recommendations.

‘Sir?’

‘For the manner in which one might best take one’s own life.’ Simmons is at times amazingly quick to apprehend, and at others needs clarification. I wonder where his brain goes during the latter periods. I do not think of him as having an imagination, but I am perhaps wrong. It occurs to me that I have not in my life considered what happens inside other people’s heads. I must write a poem about it someday.*

‘I see.’ He is pensive for a moment, then says, ‘I understand that drowning is, all things considered, not a bad way to go.’

I am disappointed in him, and tell him so. ‘I’d have thought better of you, Simmons. If I drown myself, my corpse is likely to float downriver and wash up on a foreign shore and frighten to death some poor Froggy* child building castles in the sand — and all because you had a frankly quite selfish aversion to a few minutes of brains clean-up. You ought to be ashamed of yourself.’

Читать дальше