Lancaster’s mouth still moves soundlessly. ‘I’ve shocked you,’ says Lizzie with pert accusation.

‘A bit,’ mutters Lancaster.

‘I see,’ she says. ‘I’m sorry.’ She doesn’t sound sorry. Or at any rate, she sounds sorry only that he is not more liberal in his thinking.

She is being deliberately cruel, and he has not yet noticed. I am passing proud. I have said that Simmons raised us, which is true — but I like to think that, being so much older than she, in a large part it was I who raised Lizzie.

‘I didn’t mean to make you angry,’ flails Lancaster.

‘I’m not angry,’ she replies with a dying fall. ‘Just disappointed.’

Lancaster looks as though he’s going to cry.

‘Oh come now!’ says Lizzie, breaking out in a charming little smile. ‘Laugh! If I’d dreamed at thirteen you’d be this stodgy my heart would have broken.’

Lancaster is adrift. Lizzie at last wearies of her game and takes pity on him. ‘Tell me about the north,’ she says again.

He clutches at the question like a life preserver. ‘What would you like to know?’

‘Everything,’ she says. ‘But you could start by telling me where you went.’

‘You read about Greenland?’

‘Yes! Did you really ski all the way across it?’

Lancaster leans in conspiratorially and says, ‘Truthfully, no. My binding broke with a hundred miles to go, so I walked the rest of the way. Then by balloon from the east coast of Greenland to the west of Iceland, where I rendezvoused with Dr Nansen. We went together on his ship, I forget her name—’

‘The Fram ,’ says Lizzie promptly.

‘How d’you know that?’ demands Lancaster, looking at her even more intently.

Lizzie shrugs. ‘I know things.’

Lancaster cocks an eyebrow. ‘Well, then you know he built the Fram especially for Arctic waters.’ She nods. I have no idea what they’re talking about.* ‘I’d have preferred to take my own Daydream, but the poor girl wouldn’t have made it through the ice. When the pack got too thick I took my leave of the good doctor and skijored to Svalbard. Skijoring is—’

‘When dogs pull you on skis, I know. You were saying?’

He beams at her precocity. ‘From Svalbard I tried several times to punch north, but each time was turned back by weather. Damned good sport, but I’d finally had enough, and was completely out of supplies — I’d been living on walrus meat for the better part of a year, and between the two of us I was beginning to put on some blubber myself.’

Lancaster laughs at his own joke. It is clear that his muscled frame has never carried an ounce of blubber in his life. ‘Even so,’ he continues, ‘I’d likely have stayed longer, but there was a blizzard and reports of a troll* and it seemed time to leave. I tramped down the spine of Norway, bought a schooner in Bergen, and set sail for home. Nothing much happened on the way — a few detours and a shipwreck, but nothing of note.’

‘That sounds so marvellous,’ says Lizzie dreamily. ‘I’d so like to do that someday.’ Which is worrisome. When Lizzie gets an idea into her head it can be a dangerous thing. I only hope that Lancaster will discourage her.

‘You should,’ says Lancaster. Damn him.

Listening to them makes me a little sad. They have achieved within an afternoon’s acquaintance a conversational ease which Vivien and I never had. At first I think it is because of Lancaster’s natural effortlessness in all things; but the more I watch, the less I think that is so — after all, he could barely say a word to her five minutes ago. Nor is it Lizzie’s quickness of speech and wit; she is hardly quicker than I, and if anything her speed throws Lancaster off. No, it is something that I cannot put my finger on. Something ineffable. It is to be found in neither one of them separately, but seems to be some sort of chemical reaction set off by the meeting of their minds. Perhaps had Vivien and I experienced that, things would have been different.

Lancaster is still talking, and they appear to have completely forgotten I am in the room. ‘Someone, I can’t recall who, wrote that exploration is nothing more than the physical manifestation of the lust for knowledge—’

‘Appleblossom.’

‘What?’

‘Apsley Appleblossom wrote that.’

‘So he did, by Christ! You amaze me. He also made a salient point, though, which is that only rarely do explorers actually enjoy themselves during expeditions. He notes that tramps like mine are often enjoyable only in retrospect; while you’re actually on them you’re generally hungry, lonely, and bloody freezing.’*

‘Is that always the case, though?’ asks Lizzie. ‘I feel like there must be moments even as you’re cold and hungry and sleeping on the ground when it’s really wonderful.’

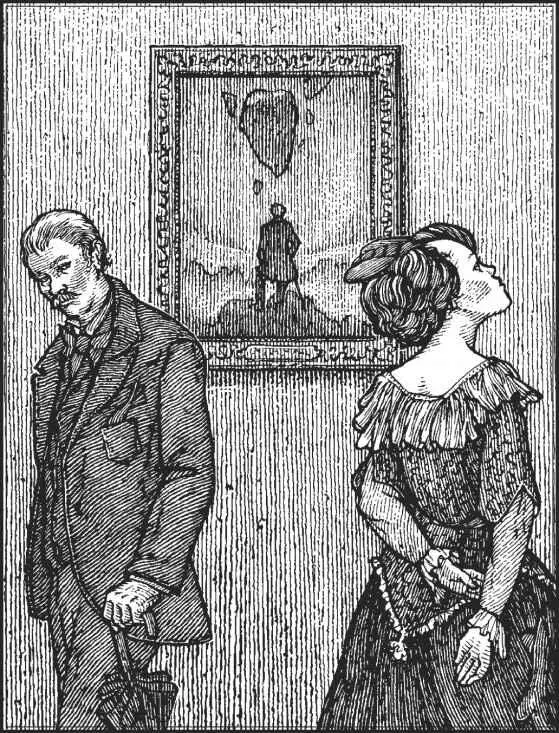

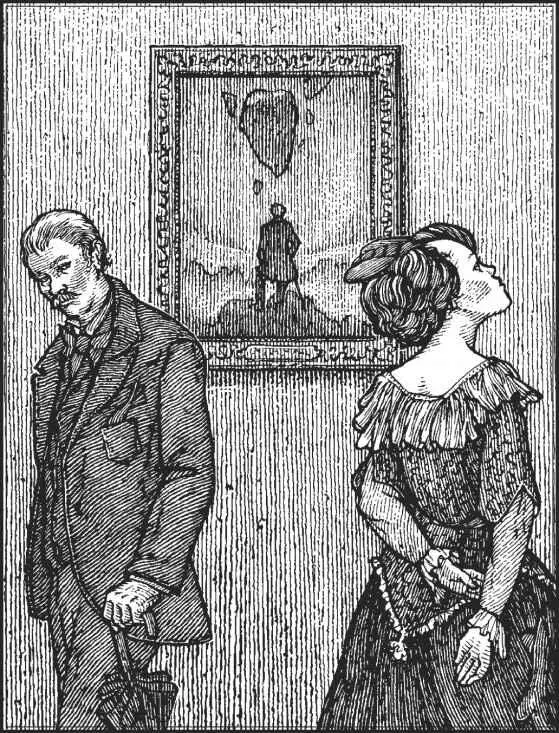

‘Oh, absolutely! Don’t get me wrong, you’ve absolutely got your Friedrich moments.’

‘Your what?’

‘Your Friedrich moments,’ he repeats. ‘Looking out at a sea of fog.’

‘Who is Friedrich?’ says Lizzie.

‘Caspar David Friedrich,’ says Lancaster. ‘He painted Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog .’

‘I’m not familiar with it.’ There is a hitch in her voice.

‘No, no, surely you’ve seen it. It shows from behind a man standing alone on a promontory, looking out at a vast expanse of clouds and mountains.’ I brace myself. Lancaster is on dangerous ground. He is about to discover something about Elizabeth Savage which she does not want discovered. It occurs to me that I should warn him somehow, but I do not. I am intrigued. It is like watching a person walk into a patch of quicksand — you know that you really ought to call out, but you cannot; you can but watch in morbid fascination.

‘That sounds lovely,’ she says with gritted teeth, ‘but I’ve never seen it.’

‘Oh, I’m sure you have,’ says he. ‘Everyone has!’ (‘Oh sir!’ I cry in my head. ‘Oh sir, speak no more!’)

‘Well, clearly everyone hasn’t ,’ snaps Lizzie.

Lancaster cannot let it lie. ‘I mean, every educated person!’ he says. ‘Every art lover. I can tell just by looking at you that you spend huge amounts of time at the National Gallery. It’s written all over you. I’m not wrong, am I?’

‘No, actually, you are.’ I have never seen her this annoyed.

‘Indeed? Well my God!’ he cries. ‘Have I found a breach in your defences at last? This is fantastic!’ I begin to wonder whether it isn’t stupidity but in fact bravery in the big adventurer. He must know what treacherous ground he treads. My respect for him continues to grow.

‘It’s not a breach ,’ says Lizzie, hugely indignant. ‘I just haven’t gotten around to art yet. I know books . Art can wait. I’m sure it’s lovely, and I’ll get there. It’s not a breach.’

Lancaster is gleeful, and does not bother to contain himself. I again imagine him with sword in hand, leading a small brotherhood in a desperate battle. It would be a sight to see. ‘It is!’ he cries. ‘I can’t believe it! You know everything in the world but you don’t know a damn thing about art.’

‘Of course I do!’

‘Bosch and Bruegel,’ says Lancaster. ‘Who copied whom?’

‘What?’ Lizzie is becoming flustered. Lancaster charges on.

‘Who’s Gustave Courbet?’

‘A painter.’

‘What did he paint?’

‘PAINTINGS.’

‘Who sculpted Michelangelo’s David? ’

‘I DON’T KNOW!’

‘ Michelangelo’s David ,’ he says, and even I have an inkling.

Читать дальше