I have no idea what he is talking about. ‘Naturally,’ I say.

‘You didn’t read about them, did you?’

‘No.’

‘Well never mind, old boy. Don’t have to lie about it. No shame in a little ignorance now and again.’ I consider objecting, but he is already describing his trips and I cannot get a word in edgewise. ‘They were your standard expeditions: sunburn, frostbite, sleeping on rocks, maggots in your flesh, near starvation. You know.’

I do not know. How would I know? Why on earth would I have any notion? ‘Delightful,’ I say.

‘Oh, but it is!’ he exclaims. ‘You have no idea. Most wonderful thing in the world, travelling. What was I saying?’

I am not interested in his stories, but I am making mental notes on his person. He strikes me as a perfect specimen upon which to someday base a character. He is poetical in the extreme, and the creative part of my mind, which is most of it, considers ways I could utilise him. The trouble is, no reader would ever believe the almost godlike beauty of the man. It is as though light radiates from his skin. ‘The Geographical Society,’ I say.

‘Oh yes! Well, things were going along nicely until I found El Dorado.’

‘El Dorado doesn’t exist,’ I say. Though I suppose maybe it does after all. My wife was just abducted by the Devil. Surely El Dorado isn’t as fantastical as that.

‘That’s what they said, the faithless beggars!’ cries Lancaster. ‘I told them I’d found it and they laughed in my face and told me to prove it.’

‘That sounds reasonable,’ I point out.

‘Well maybe so, old boy,’ he says, frowning, ‘but it’s not strictly speaking polite. Anyway, I went back with a bevy of ’em, but couldn’t find the damn place again, and that was the beginning of the end. The trouble with the Geographical Society is, they’ve no imagination. Well, I’d had quite enough of the whole thing, and it wasn’t as though I needed their money, so I left the Society and ever since I have independently been finding remarkable things which the scientific community blithely assures me don’t exist.’*

I do not voice my scepticism, and he goes on.

‘Now, I tell you all this not to toot my own horn, as the saying goes, but because I want you to understand that I’m with you, by Christ, and we’ll see this thing through to the bitter end. I’ve been to El Dorado and I’ve stumbled across Shangri-La and I’m damn near to finding Atlantis, so if you’re looking for a chap with whom to storm the gates of Hell then don’t worry, old boy, you’ve found your man!’

He is breathing rather heavily — if his words have not roused me, I believe they have at least stirred his own blood a little. I am glad, for it was a pretty speech — and if not for the fact that I do not like going out of doors if it can be avoided, I would doubtless have been inspired to seek the sunset. ‘Well that’s very kind of you,’ I say, ‘but I’m afraid it’s more complicated than that.’ I still do not know how to tell him exactly what I mean.

‘I don’t see why it should be,’ he replies. ‘She loves you, and you love her, and she’s my little sister, and she’s been stolen. God knows we’d go after them if it were the Frenchies who’d taken her,* so why not the Devil?’

I do not know why he keeps talking of love. There is no love in this household. I do not love my wife, and she does not love me. It is a loveless marriage, which is why I cannot write and why she confines herself to her room except when she’s throwing parties. The man is delusional. Where has he gotten these notions? ‘Well of course,’ I say, ‘but—’

‘But what? She dotes on you. You know damn well she’d never leave you to rot if it were the other way round.’

I know no such thing. I believe were it the other way round she would dance a jig. It’s finally too much for me. ‘Yes, so you keep saying. You’ll excuse me for pointing it out, but you haven’t even seen her for two years. For all you know we hate each other.’

‘Now there’s a thought!’ laughs Lancaster, dismissing it out of hand. ‘I told you, Savage, I read her letters, and it’s not every couple that’s got what you’ve got.’ There’s something about him which tells me that, I am almost certain of it, he is not lying. He truly believes that she loves me. How can this be? What is in those letters? I must read them. Immediately. My life may depend upon it.

There are very strange happenings inside me.

‘I’d show them to you, if I could — the letters, I mean, they’d warm you right from the inside — but they were all lost when the ship went down off Spitsbergen.* Damn shame, that. Never met anyone who can use words like my little sister. What was it she said? “The fact is, I’m his, all of me, and he is mine — and whatever the difference in our temperaments, we are souls entwined.” Makes a man glad to read those words, glad to know such a thing’s possible, eh?’

Something is wrong with my chest. I cannot breathe. I do not know what is happening. My blood is not pumping properly, my eyes are not focusing, my ears are ringing, I can feel a feverish flush rising to my cheeks.

‘You alright, Savage?’ asks Lancaster, eyeing me with concern. ‘You’re looking poorly.’

‘Indeed,’ I say. ‘I’m feeling… peculiar. Peculiar feelings. I’m going to lie down. Make yourself at home. Lizzie will come find you.’ I raise my voice and call, ‘LIZZIE!’ Then, without a backward glance, I flee.

Six In Which I Visit the Grandest Shop in the World, Where I Meet a Very Poetical Person, After Which I Have an Earth-Shattering Epiphany

I hurry up the stairs and into my room. I lie down on my bed. It is a great four-postered monstrosity that used to belong to my parents. I hate it. I have never spent a night in it with Vivien. I have never spent a night anywhere with Vivien. The week of our wedding I was in a fit of composition, and I dared not waste any time consummating our marriage. I wonder if things would have been different if I had.

It is a silly thought. Vivien is now in Hell, and I am lying on this wretched bed thinking of her. I do not understand Lancaster’s words. His talk of letters. Could there truly have been letters?* I do not know. I was not aware that my wife writes — wrote — letters, but I was also not aware that she wrote poetry. One learns the most alarming things.

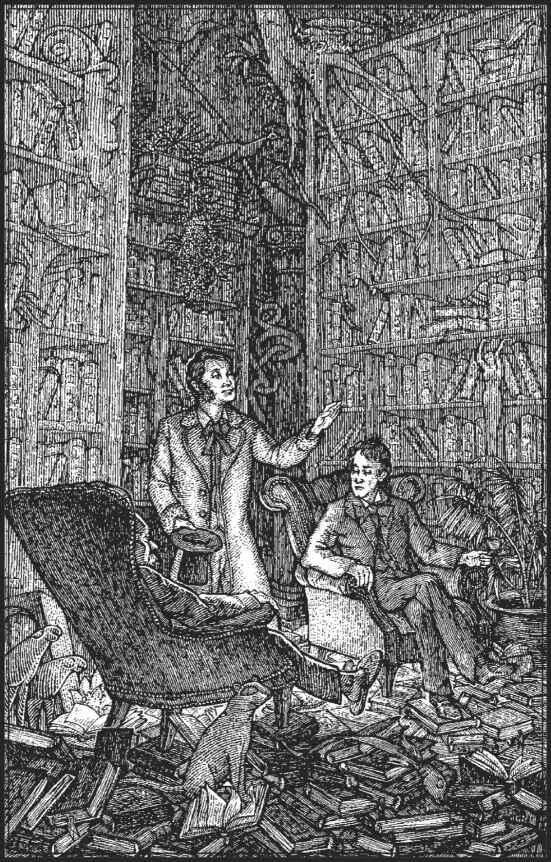

I hate my room. I hate my house. I hate being indoors. I need to get out of doors. I still cannot breathe. I need to be outside. I tiptoe to the door, open it a crack, peer through. No one is on the landing. I can hear faint voices from the study and a shout of laughter. Lizzie must be entertaining Lancaster. I wish them well, and if he touches her I will kill him. I do not know where Simmons may be.

I creep down the stairs. I do not like creeping within my own home, but I cannot bear to see anyone. I do not want to speak. I do not believe I would know what to say. I do not know what to think. Something inside me is broken. I slip into my overcoat, for it is a chilly November day and my smoking jacket will not be warm enough and I hate being cold, and I slip out the front door.

The yellow fog is wrapped round the house waiting for me, and I plunge into it. I love the fog. The sounds of the city are muffled by it, made mysterious and poetical. It is a poetical city. Why have I never noticed that before? Perhaps I have. I do not remember. I do not know. I do not know a great many things, I find. Everything seems somehow different. Perhaps I am dreaming. I wonder if that is the case. It would make explicable many things currently inexplicable. I pinch myself. I do not wake. I am not asleep. I am not dreaming. Unless I am in a waking dream. I may be mad. I may have stumbled into a fairy tale, but I see no dashing princes about, unless Lancaster be one. I imagine him holding a sword leading an army. It is easy to do. If I were a great painter I should paint him as St George. I have never had a care about my body, but watching the way Lancaster moves I was struck for the first time in my life that I am small and weak. If I were otherwise, would Vivien have loved me? I do not know.

Читать дальше