We looked at each other with resignation, because we already knew from the twins what was coming: lots of radios, turned right up, broadcasting different games from behind the windows, two or three lads in a doorway singing that chant the old man loves, a bunch of kids audibly kicking a ball around somewhere. And us, like a bunch of idiots, humouring him. That’s not music, he said; you think one swallow makes a summer? Well I felt like chucking it all in and leaving then, but the twins were undeterred, insisting that no, the music of Sundays had not disappeared, that in the barrios you could still hear it in any street. And then with apparent spontaneity, they suggested we all go for a stroll to see if they were right. Showtime, Mom whispered to me, and Uncle Antonito snorted angrily.

We filed outside in a kind of procession. The twins went at the head; behind them was Dad, trying to soothe Uncle Antonito; then came Aunt Lucrecia with my grandfather. As we were leaving, Mom grabbed my arm and said: Wait, let’s stay back a bit because this is the most ridiculous charade I’ve ever seen. So we went last of all.

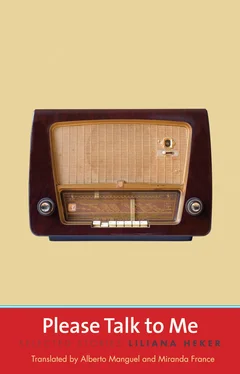

We were walking very slowly, following the twins, and straightaway we began to hear radios. One or two in front of us, another, at full volume behind us, others, still faint, further off. From behind a thick wall, the voices of children could be heard; they were saying pass to me, they were saying come on, ball hog. Three boys sitting in a doorway started singing, just as we passed them, You should see our goalie / What a Star! / He can stop a penalty / Sitting on a chair / If the chair breaks / We give him chocolate / Come on Boca Juniors / Down with River Plate! I stole a sideways glance at the old man; for the first time that afternoon he appeared to be smiling. Cheers came from one house; their echo seemed to expand in the street. On the other side of the wall, the boys’ shouting grew louder and more passionate as though this were no longer a performance but something on which their lives depended. The afternoon quietened, the noise of buses and cars fading away, while the voices on the radio got louder and more numerous, they were saying Negro Palma intercepts, they were saying Francéscoli moves forward, they were saying header from Gorosito, Márcico’s waiting for the pass. I heard, or thought I heard, Rattin’s name, but it couldn’t be — wasn’t he the one the old man said insulted the Queen back in the 1960s? I heard Moreno takes it on the chest, kills it with his left foot, turns and… Goooal! shouted the boys in the doorway, goooal! from the windows on that block, and from a different building too, and another further away. And some element of that shout lingered, as though caught in the air, I saw it in Dad’s face, and in Aunt Lucrecia’s; even Uncle Antonito seemed to sense it, something like a net being woven around us, gathering everyone together in the benevolent Sunday afternoon. Mom squeezed my arm, the twins looked at each other with amazement, the old man shook his head as though to say that it was true after all, the music was there, the music was still there. The doorway boys roared, the people in flats started arguing from one balcony to another. Mamita, mamita, shouted a boy coming towards us, and a startled mother looked up from the kitchen sink, elegant dodges were celebrated on vacant lots and patches of grass, Oléee-olé-olé-olá, they chorused in the stands, Look at us now, look at us now, they shouted in the streets, Come on Argentina / we won’t stop cheering you, they sang in the halls, the roof terraces, the courtyards. And from far away came an unsteady noise, a murmur that kept growing louder, emanating from the very edge of the afternoon, that hour when people start listening to old dance songs and mulling, with contentment or bitterness, over the events of the Sunday that is ending. We saw them approaching, ever clearer in the hazy light of dusk, blowing their horns in time, a surging crowd of people waving blue and white flags, blue and red flags, red and white flags, gold and blue flags. Everybody in the neighbourhood came out to welcome them to the party, and the whole city rang with noise, like one unanimous, jubilant heart.

Afterwards would come the melancholy of Mondays, and there would be stories of fear and death, and later we would close the old man’s eyes for the last time. But we would always know that under the sky of a distant Sunday, there had once been a music that had made us briefly happy and peaceful.

Señora Brun had almost finished getting ready to visit her friend Silvina when she noticed a little water coming from the spout in the bidet. She tried firmly closing the taps, but that didn’t help. Then she opened them fully so as to close them again with more force, but no matter how hard she tightened them, hot water kept jetting out, now with enough pressure almost to reach the rim. She tried opening and closing the hot water tap again, to no avail: the flow was undiminished. Now the floor was wet and the bathroom full of steam and she herself was soaked so that there was no option but to turn off the hot water at the stopcock, change her clothes, and set about finding a plumber.

Not easy. The one who usually came to her house had jobs lined up for the next three days; the one the Neighbours’ Association used couldn’t come until the following afternoon. Finally, a plumber whose number was given her by the doorman in the building next along said he could be there in half an hour.

Señora Brun went downstairs to ask the doorman if the plumber was trustworthy.

‘I don’t know him, Señora,’ said the porter. ‘But these days you can’t even trust your own mother.’

That was hardly reassuring but what choice did she have? She rang her friend Silvina and explained the setback.

‘It’s probably nothing and I can come later on,’ she said.

As a precaution, she locked away her wallet and jewellery; she also rang her husband to tell him about the incident and to let him know that an unknown plumber was about to come to the house. Her husband would know what to do if anything untoward should happen.

The plumber, a wiry man in his fifties, arrived half an hour later, as promised. To Señora Brun’s consternation, he wasn’t alone, but accompanied by a large youth with long curly hair gathered in a pony-tail.

‘Oh I didn’t realise you would need to bring an assistant,’ she said, very pleasantly. ‘It’s such a simple little job…’

‘We haven’t seen it yet, Señora,’ the plumber said curtly.

He seems rather short-fused, Señora Brun thought. She led both the men to the bathroom and explained the problem.

‘Where’s the stopcock?’ asked the plumber.

‘Do you need to open it?’ The plumber’s expression was withering. ‘Of course, of course, bear with me,’ she said quickly, ‘I’ll go and do it.’

She went to the kitchen and opened the stopcock. Water started gushing out again. The assistant was turning something with a kind of spanner while the plumber gave him instructions.

‘Oh dear, the whole bathroom’s getting wet,’ Señora Brun said.

‘It’s water, Señora,’ said the plumber. ‘It will dry.’

She sighed.

‘Do you think that…?’

‘Now we need to turn off the stopcock,’ said the plumber.

She ran to the kitchen, turned it off and came back.

‘I’ll need a cloth,’ said the plumber.

She went to look for a cloth. When she came back with it the plumber was working. ‘Dry this up a bit,’ he said to the assistant. To Señora Brun he said, ‘It’s the washer in the hot water tap, but the transfer valve is broken, too. Did you know that it was broken?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘It’s always worked perfectly.’

Читать дальше