For Zafar Moradabadi,

and in memory of my grandfather

Dr MD Taseer

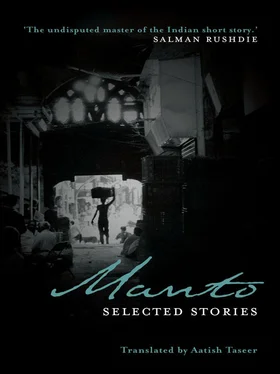

Introduction: Travellers of the Last Night [1] Loosely derived from Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s poem, ‘Sham-e-Firaq’

When at the age of twenty one, I went to Lahore to meet my Pakistani father for the first time in my adult life, I was given, in addition to a new Pakistani family, a copy of my grandfather’s poems. It was a blue book, simply published, with flames dancing on the cover. Those flames stood for aatish, fire in Urdu, because the book’s title — and the origin of my name — was aatish kada, fire temple. This picture of the flames was all I could make sense of at the time — the poems were in the Urdu script, of which I knew too little to read even my name. My grandfather had died in 1950 when my father was only six. This book then, both for being my only patrimony and for being written in a script I couldn’t read, was a mysterious gift.

But deeper than these particular circumstances was another mystery: the mystery of why the script should have been unfamiliar to me at all. My mother’s family were Sikhs from what is today Pakistani Punjab; they would have lived no more than a few hundred kilometres from where my father’s family lived; they would have spoken the same languages, namely Punjabi and some Urdu. They came, in 1947, as refugees to Delhi, which along with Lucknow, was the centre of Urdu. So how was it that I, six decades later, having grown up in Delhi, could not read my paternal grandfather’s poems?

‘They stole it! And we also let it go,’ Zafar Moradabadi said mournfully, speaking of Pakistan and Urdu respectively. He was the man with whom I had sat down, four years after receiving my strange patrimony, to conquer its mysteries.

He came to me through the Ghalib Academy, a crumbling, art deco building with pink walls and smelly carpets. Himself a poet, Zafar’s name twice resonated the names of poets before him: Zafar like the poet-king, Bahadur Shah Zafar; Moradabadi, like Jigar Moradabadi, the other, more famous, product of the brass producing town of Moradabad.

Zafar didn’t like coming to me through the Academy. I felt he was embarrassed at having to teach. Even on the telephone, he seemed to want to establish a reason other than need for teaching me.

‘Aatish? Aatish Taseer?’ he asked in his papery voice, ‘But that’s a poet’s name.’

‘Yes, sir. My grandfather was a poet. I want to learn to read his poetry.’

‘Your grandfather was MD Taseer, the poet, and you don’t know Urdu?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then it appears I have something of a duty to teach you.’

He came to see me a few days later. He had a light, gliding step. He wore a safari suit, a white woollen cap and finely made spectacles. He was of medium height with a slight stoop. His eyes were yellow, his skin dark, he had a pencil thin moustache and sores, black and bleeding, ate away at his scalp.

I saw them when I asked if he would like to take his cap off.

‘I wear it because the wool from my head has come off,’ he said, and laughed throatily. Then, folding away his cap, he revealed his bald head.

‘I can’t take the heat,’ he apologised, when he saw me notice the sores.

He sat there with his hands discreetly by his side. He asked no prying questions, he didn’t look around the flat. I asked him if he would like tea.

‘I don’t normally. My constitution is quite sensitive.’

We started badly. I said I didn’t want to learn to write, only to read.

‘You can’t take a language, break it into pieces, take what you like and leave the rest for the Pakistanis. What if you find you need to write?’

‘But I always write on my computer.’

‘Yes, but what if you’re in a poetry reading and you want to scribble down a couplet.’

‘I can write it in Devanagari.’

His face filled with placid disgust.

‘Then perhaps you should learn Hindi.’

‘My grandfather’s poetry…’

‘I could have it transcribed for you in Devanagari. Problem solved.’

‘Listen, please, I want to read Faiz, Manto, Chughtai…’

‘All available in Devanagari.’

‘I’ll learn to write.’

His face bloomed with affection and concern. ‘You know you have a responsibility. You’re a poet’s grandson; your great-uncle was Faiz; you have a tradition to uphold. I’m not saying that you should write poetry. I would never send you into poetry. It’s finished. Look at how I’ve suffered. I tell my children all the time that poetry is finished. But what’s been done is still there, for you to read and know. You say you want just to read; even that will only come when you can write.’

I offered tea again. He said he didn’t normally drink it, but he would today.

When Sati came in with the tea a few minutes later, Zafar was saying in Urdu that life had forced him to become an intellectual mercenary. Those two words, neither of which I knew, provided us with our first thrill as teacher and student. We stumbled about for a bit, coming up with mental soldier, then I was sure I had it. ‘Think tank!’ We backtracked and gave up. It was only when he explained further that I understood what he had meant.

‘I gave birth,’ he said, ‘to seven PhDs before I was born, and since my own birth, I have given birth to two more. It’s dishonest, I know. I take money to write people’s theses for them, undeserving people. It’s wrong, I know. But I only ever did it from need. I feel that makes it less wrong.’

‘How did you start doing it?’

‘I used to work as an accountant,’ he replied, ‘but that slipped away from me. The accounts were computerised. I needed money badly. I even had a breakdown, you know?’

‘What kind of breakdown?’

‘A nervous breakdown. I was lucky — a south Indian doctor helped me. Only he knew what it was. Without him, I wouldn’t be here today. There was a threat of my brain haemorrhaging.’

‘Can that happen from a nervous breakdown?’

‘Yes, my head used to become so hot, my wife couldn’t touch it.’

I began to think of his sores differently.

‘He used to tell me, “You have to stop thinking.” I said, “Doctor saab, it is my nature. Can you order a flower to stop giving off its scent? It is God given.” ’

He shook lightly with inaudible laughter, finishing in a wheeze.

‘At that point,’ he said, ‘a PhD candidate came to me. He had a famously strict advisor. A man who used to tear up theses if he didn’t like them. He asked me to help him. I said, “Listen, I can’t do this. I haven’t done your research. I don’t know what you wish to say.” But, he went away and came back with all his books, begging me. I said, “Let’s just try it. If he likes it, then we’ll continue.” He agreed and I wrote the thesis.’

‘Did the professor like it?’

‘He said it was the best thing he’d read in twenty years of advising. After that, word spread,’ he added bitterly. ‘Would you like a cigarette?’

‘Yes,’ I replied though I wasn’t really a smoker, ‘but outside.’

We smoked a Win cigarette on the balcony. There, overlooking heavy Delhi trees, he brought up money.

‘I can’t take less than five thousand,’ he said, taking back the blue and white packet.

‘A month?’

‘Yes.’

My face became hot with shame, but I said nothing. Neither his sores nor his haggard face could have expressed his poverty more extremely. He wanted five thousand rupees for two — three hours, five days a week. I had just paid twice that amount at Barbarian gym. I didn’t know how to say I wanted to give him more. I didn’t want to upset his calculations. So we settled at five thousand a month and Zafar began to come every day to teach me Urdu, from three to six.

Читать дальше