Ever restless, anxious and melancholy, subject to gout, Conrad relocated from his jerrybuilt rabbit hutch’ to Ivy Walls Farm on the edge of Mucking Marshes.

The glamour’s off .

‘The glamour’s off,’ Marlow says in Heart of Darkness . Maps have lost their attraction (since they found their way, as a metaphor, into the mouth of George W. Bush). But Conrad appreciated them, their fictional possibilities. A shop-window in Fleet Street. Author peering over his character’s shoulder, nudging him aside to get a better look at ‘the biggest, the most blank’ space on the map of Africa. A space now filled by busybodies and exploiters, the riffraff of Europe. Filled with rivers.

I visited, every time I walked towards Tower Bridge, a window of my own in the Minories: nautical charts, oceans of numbers. The conjunction, mathematical symbols and river, was provocative. Voyages I would never make, voyages I remembered (without having experienced them): Arthur Norton sailing from Tilbury on The Albemarle , 1858, bound for Colombo. The map he drew, in blood-brown ink, each week concluded with an X: ‘Total distance 1,400 miles.’

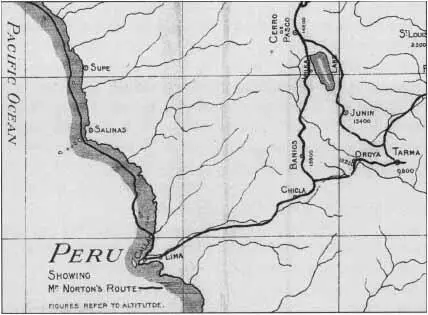

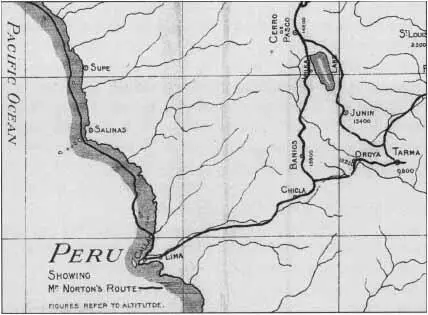

The white of the map, that’s what seduces us. Arthur’s speculative, foldout version of Peru, the Pampa Hermosa, white as meat in a bottle. Red lines representing Arthur’s route, Chicla, Banios, Cerro de Pasco, Huarica, Ambo, Huanuco. River-threads like skull cracks, brain fissures. The hours I spent poring over Arthur Norton’s unreliable chart. The days on the road, heading for Beckton Alp, Creekmouth, the Eastbury Levels, London’s empty quarter. Or so it appeared. At a distance. The map-makers found nothing to colour between the Royal Albert Dock in North Woolwich and Ferry Road in Tilbury. The last of England. The empty Custom House, railway terminal, disembarkation sheds. Deserted platforms and overgrown railway tracks.

It’s not that there’s nothing of consequence in the white bits, geographers are too lazy to see it: rifle ranges, landfill mountains, wild nature enveloping concrete, oil-spill on the shoreline, rock pools in threadbare tyres.

Conrad saw it, loved it. Going out on the river, in the yawl Nellie with G.F.W. Hope, kept him sane. (Fountain knew about this. That’s why she picked Grays. For the marina , the squadrons of sailing craft, riding at anchor, in the lee of that distant monster, the Tilbury Power Station. And Hope himself, she knew about him. His name: George Fountaine Weare Hope. Fountaine Hope! Weary Hope! Marina was writing me a letter in code. And I was beginning to crack it. As soon as possible, I would make for Fenchurch Street, repeat her fictional journey.)

Hope and his friends, the accountant W.B. Keen and the lawyer T.L. Mears, we are told, become models for the frame-narrative of Heart of Darkness . Waiting on the tide at Gravesend, mother river, in the abeyance of twilight, spinning yarns. In parts of the map that are not overwritten, worked out, everything bleeds into everything, sea and sky, truth and legend; defences are down, faces merge into protective beards. We confess, we lie. We make up stories.

The essay I abandoned, as an act of homage, Conradian lethargy, elective malaria, opened in Hackney. Voice-over by Michael Caine at his most soporific. (Try for Caine, get Bob Hoskins.) Not a lot of people know that Joseph Conrad, taking London as the base for his life in the British Merchant Service, found lodgings in Stoke Newington. May 1880. Dynevor Road. Dynevor Road, a tributary running to the west of Stoke Newington High Street, is a near neighbour of Evering Road (running to the east). Hackney’s own heart of darkness: the basement flat of hostess ‘Blonde Carol’, where Reggie Kray butchered Jack ‘the Hat’ McVitie. (Jack’s trilby as mythical as Conrad’s cannonball bowler.)

The Lambrianous started scrubbing the carpet with hot water from the kitchen. When the worst of the mess in the living-room had been dealt with, McVitie’s body was wrapped in an eiderdown, dragged up the stairs and placed in Bender’s car. Ronnie told him to drive away. Then somebody remembered McVitie’s hat. It was his trademark and could easily identify him. When he dived at the window it fell outside. It was retrieved.

When I dived at the window, Polish darkness imported to Lea Valley Congo, the theoretical structure of my Conrad-in-Hackney essay fell apart. Free-associating connections hissed like a badly wired tenement in a thunderstorm. Gravesend. The port of Boma. Conrad’s meeting with Roger Casement, the only sympathetic personality in a swamp of African madness and corruption. Dysentery. Fever. Soul sickness. Skeletons nailed to trees. Carpets of skulls. Broken in body and mind, branded with the mark of what he had witnessed, the future, Joseph Conrad returned to London.

This is what I discovered, this is what amazed me, a mad, undigested narrative of colonialism and fiscal voodoo, earthed in Dalston. Heart of Darkness brought to ground. Joseph Conrad taken to the German Hospital, Dalston Lane, London N16, suffering from malaria, rheumatism, neuralgia. And worse. The Congo diaries, as fantastic as the black forgeries presented at the trial of Casement, were kept at his bedside.

Saw another dead body lying by the path in an attitude of repose … At night when the moon rose heard shouts and drumming in distant villages. Passed a bad night.

With many more to follow. It’s not the same moon. I don’t care what they say. From my window, writing the Conrad piece (raiding other men’s books), I watched a cigarette-end moon, glowing ash, floating over the wet roofs of the German Hospital: one ward brilliantly lit. No Germans left. No hospital. An improvised film set. A Freudian drama. A naked patient being given the water treatment.

But that is not why I gave up, why I started walking, making reports from a real landscape. It was the discovery of the arbitrary connection — no accident, no remission — of Joseph Conrad, first officer, and my great-grandfather, Arthur Stanley Norton. (Names that shift, migrate. H.M. Stanley’s painstaking travel journals dressing the piracy of the Société Anonyme Belge pour le Commerce du Haut-Congo. David Livingstone, febrile and driven: a Xerox of Robert Louis Stevenson. A divided Scotsman looking for the right place in which to die.)

Arthur Norton’s fatal expedition to Peru resulted from the loss of funds amassed over years of labour in the Ceylon tea plantations. Conrad was also the victim of well-meant but devastating advice (if you have to pay someone to tell you what to do with your money, it’s gone). South African gold mines. Two men, who find themselves, passenger and officer, on a voyage from Amsterdam to Java, The Highland Forest , 1887. Norton, amateur essayist, limping around the deck, talks literature. Conrad talks weather and money. Norton, who has a way of teasing out secrets, encourages the new Englishman, the cultural migrant, to read aloud from his first composition, The Black Mate .

Conrad talks of South America, ‘the land of the ancient Inca’, which extends ‘along the coast for 3,000 miles, including what is now Colombia, Ecuador, Chili, and Bolivia’.

My great-grandfather remembered the conversation, made a note of it in his privately published pamphlet, Arthur Norton: The Story of His Life & Times as Told by Himself . He took Conrad for a Frenchman. From the south, Marseilles? The merchant mariner had the disconcerting habit of saying nothing, polishing his monocle, staring at you: butterfly on a pin. Chin up, beard primed, fists thrust deep in the pockets of his nautical jacket. Like Cutcliffe Hyne’s Captain Kettle.

Читать дальше