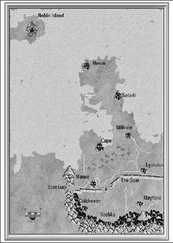

Kibbutz Metsudat Ram nestles in a long, narrow valley, near the bed of the River Jordan. The valley is a tiny stretch of the greatest rift on the surface of the earth. It starts in the north of Syria, and runs down through desert gorges and across broad plains, divides the Lebanon mountains from the Anti-Lebanon, until it becomes the valley of Ayyun on the border of Lebanon and Syria, near the little town of Banias. Here these gentle streams come together to give birth to the lovely River Jordan, which cascades softly into the northeastern corner of the land of Israel, a region of unparalleled beauty, dotted with white buildings of kibbutzim, villages, and little towns. The Jordan then flows on southward, with the hills of Galilee rising gently from its west bank and the bleak ranges of Hauran, Golan, and Bashan to the east. The water collects gracefully in the Sea of Galilee, Lake Tiberias or Kinneret, a sapphire in the setting of the land. It was in this region that we settled and founded our kibbutz home.

From Lake Tiberias the Jordan flows on to lap against the base of the dark Mountains of Moab, to fall finally, exhausted, into the arms of the Dead Sea, from which it never escapes, except in the form of a scalding vapor. But the gigantic rift stretches on southward, riverless now, along the valley of the Arava, from which rise the mountains of Edom, slain in a blood-red magic that at sunset takes on a purple hue. By the new town of Elat on the shores of the Red Sea the primeval fissure adopts the form of a lonely tongue of sea, bounded on both sides by the desert, with no strip of verdure to intervene between the water and its thirsty foe. This gulf is a slanting arm of the Red Sea, itself the extension of the monstrous rift, as its long thin shape testifies. Beyond the Red Sea the fault flows on through the tropical forests of East Africa, and farther still, beyond the equator. As if some dark power had tried to cleave the earth asunder with a mighty ax blow, but changed its mind before the deed was completed. A convulsed power seized by deep gloom in mid-action left this scar with its wild beauty.

In the course of its travels the gigantic rift encounters a variety of climates and landscapes, but for the greater part of its length it is bounded by mountainous deserts, which is why it is all hot and humid. We live at one of its deepest and warmest points. Its geological structure almost entitles our valley to call itself a canyon. For a thousand years the place was a total wilderness, until our first settlers set up their tents and made the desert bloom by the latest agricultural methods. True, a few Arab fellahin dwelt or wandered here before our arrival, but they were poor and primitive, in their dark robes, and easy prey for the hazards of the climate and natural disasters, floods, drought, and malaria. No trace remains of them except some scattered ruins, whose remains are gradually fading away and merging, winter by winter, with the dust from which they came. Their inhabitants have fled to the mountains, from where they hurl their baseless, senseless hatred down at us. We did nothing to them. We came with plowshares, and they greeted us with swords. But their swords rebounded against them.

In the span of a single generation we brought about a forceful and spectacular revolution, but we paid dearly for our land in blood, as is testified by the memorial to Aaron Ramigolski, our first victim, who left his family and his home in Kovel, on the Polish-Russian border, to be killed here by plotting enemies. There is an allusion to his name in that of our kibbutz. But the secret of success is not to be sought in the heroism of our founders. Far from it. The secret is, in the phrase of our comrade Reuven Harish, purification. That is why we invite you now to stand with us at the entrance to the pleasant dining hall and examine the faces of the men and women assembling there.

They have washed away the traces of dust and sweat in a cold shower, and now they are gathering in little groups, dressed in simple, clean clothes, for the communal evening meal. Most of the old men are not good-looking. Their sunburned faces are battered and furrowed, but their general appearance is one of strength and physical well-being. They are tanned, their features are open and forceful. Some are bulky, like Ezra Berger, others, like Reuven Harish, are tall and lean. Some, like Mendel Morag, the carpenter, and Israel Tsitron, the banana man, have a distinguished head of gray hair. Others, like Mundek Zohar, head of the regional council, or Podolski, the mechanic, who also draws up the work rota, are more or less bald. All of them, however, radiate a feeling of security and contentment. You will hardly find among them the typical peasant face, with that dense, closed look which comes from grinding toil. On the contrary. In their faces, and in their gait, as well, you see the signs of a lively intellect. They are lively men. As they come close, we can hear their confident voices raised in friendly argument, reinforced by animated gestures.

Let us turn now to their companions, the older women: Esther Isarov, who is still commonly called by her maiden name, Esther Klieger, despite her seven children; Hasia Ramigolski, wife of the kibbutz secretary Zvi Ramigolski (the brother of the late Aaron Ramigolski); Bronka Berger, Gerda Zohar, Nina Goldring, the cook, and the rest of them. Their appearance is saddening, if only for an instant. For ideological reasons the kibbutz does not allow its women members to preserve their looks by means of cosmetics, and this policy has left its mark on the older women. You will detect no sign of dyed hair, rouge, mascara, or lipstick. But in the absence of artificial aids to beauty, their faces have a simple, natural appearance. At first sight, though, these women have a rather coarse look. All things considered, they look very much like the men, with their wrinkled faces filled with controlled strength, the stern network of furrows round their mouths, their dark, undelicate skin, their gray or white or even thinning hair. Some of them are bulky, others thin and angular. Their gait, however, like that of the older men, expresses a strong inner sense of security and confidence. Do not make the mistake of thinking that some of them have a cruel look, like that rather bored woman over there. The expression which you interpret as one of cruelty is really one of asceticism. The one you pointed out is a widow called Fruma Rominov, who is in charge of the infant school. Her son, Yoash Rimon, was a young officer who was killed in the Suez campaign, and his name is inscribed on Ramigolski's memorial. In future, stranger, you will be advised to refrain from hasty judgments that mistake suffering and asceticism for cruelty. Fruma's surviving son, Rami Rimon, is due to be called up for his military service in a few weeks' time. Let us pray that he will return safe and sound, because apart from him his poor mother has nothing left to live for.

And now the younger people are coming. Look at them. Aren't they a credit to us? Look how tall they are, the girls as well as the boys. They are all good-looking. Any exceptions there may be simply prove the rule. They are endowed with all the positive qualities we noticed in their parents, without the hardness. Their walk is agile, their movements are graceful and lithe. They have been brought up from early childhood to physical labor, saturated with sunshine and fresh air, toughened by long, arduous expeditions, exercised with sport and games. All of them are sun-tanned, most of them are fair-haired. Their hands are strong and well formed. The hubbub of voices radiates cheerfulness. Though some of them may suffer from an excess of poetic aspirations, they know how to keep them well under control. Let us follow them into the dining hall, not to let them out of our sight. In any case, we are beginning to attract attention by standing here all this time by the swing door, scrutinizing everyone who comes past on his way to supper. If we linger here any longer, our intentions will supply welcome grist for the mill of gossip.

Читать дальше