A report on security from Grisha Isarov. Grisha's delivery is gruff, but his news is good: the grim prophecies have been proved wrong. Things are quiet. No worries. Still, no one can tell what will happen tomorrow. Or even tonight. I'm no prophet. Especially when the word comes through about the Camel's Field. Meanwhile, as I said, things are quiet. Still, things were calm in '36, just before the troubles. I remember once, that winter, I was in Beer-Tuvia at the time… Yes, well. There's one other thing I have to say, comrades: this place is a hive of rumors. And that's bad. Very bad, indeed. Like the story about the shepherd who always cried wolf, wolf, and when the wolf came — you all know the end of the story, comrades. I think the moral is clear to us all. So a bit less talk. That's it.

On Thursday evenings the various committees meet. Their atmosphere is not favorable to grandiose theories; practical details are the order of the day. In the financial committee, Mundek Zohar bargains with Yitzhak Friedrich for the erection of a special building for the regional council, which is housed at present in a tumble-down shack. Mundek thinks it is high time to put up a small building. Isaac Friedrich thinks that the time is not right yet or, rather, that there are not sufficient funds available, the current year being a lean one.

In the cultural committee, the news of Dr. Nehemiah Berger's impending visit is considered. This would be a splendid occasion to organize a series of lectures on the history of socialism. The matter will be discussed.

In the educational committee, the pressing problem of delinquency is aired. The subject is Fiercely debated, and a far-reaching decision is taken: to send Oren Geva to a consultant psychologist in Tel Aviv who is employed by the kibbutz movement. This decision is to be kept a close secret.

On Thursday night, an hour before midnight, Einav Geva felt the severe labor pains that frequently accompany the birth of a first child. Tomer, perturbed and somewhat irritated, drove his wife to the hospital. He made every effort to drive the dusty truck as smoothly as possible and to avoid the potholes in the road, so as not to cause his wife unnecessary pain.

Einav entered the maternity ward at close to one o'clock. Tomer stayed for a few hours, time enough to smoke eight or nine cigarettes and joke a little with a tall, dark-skinned nurse. At four o'clock in the morning he asked the night nurses to tell his wife that he was going home now, but that he would come back that afternoon. He had to go and supervise the work of getting in the cattle fodder. He had already turned to go when the night nurse's voice stopped him.

"Congratulations it's a boy."

Tomer gaped at her in amazement.

"What, she's…. she's had it already?"

The nurse barely looked up from the papers on her desk.

"Congratulations it's a boy."

Tomer blanched and leaped toward the desk. Seizing the nurse's elbow, he asked shyly:

"Excuse me, is it a boy or a girl? Which is it?"

"Congratulations it's a boy I've told you five times already." Tomer groped in his pocket, drew out a cigarette, put it to his lips and forgot to light it.

"When am I allowed to see it?"

When she answered that he had best come back in the afternoon, he clasped his large hands and said:

"Tell her congratulations. Tell her I'll come back this afternoon. Tell her I'm not allowed to see her before then, and anyway I can't because we're getting in the cattle fodder, and I've got to be there because otherwise they'll cut the wrong field, the one by the bananas, and… never mind. Tell her I'll be back in a few hours' time. Yes. So it's a boy you say. That's very good."

Something else happened that same Thursday night.

Turquoise went out, as usual, to wait for her older friend. Titan, the bull, watched her through the bars. He breathed heavily. His breath was warm and moist. The girl saw the bull and pulled a face. Titan's eyes were bloodshot.

Behind the cattle shed were the outlines of the tractor shed. It was cold, and she shivered slightly. From the cold and from boredom she jumped lightly up and down on the balls of her feet. And then it happened.

At twenty-five past eleven that Thursday night, in the middle of a light jump, Noga Harish felt a pain. A terrible pain. A pain in her abdomen.

She stopped jumping and put a shaking hand on the spot. The blood drained from her cheeks. Her mouth fell open. Her heart froze. In a moment of sudden, fierce comprehension other, earlier signs fell into place. No. Yes.

Mo-ther, she murmured, her eyes bulging. The cold turned to a raging fever. The blood that had drained from her face flushed back into her skin. Mother.

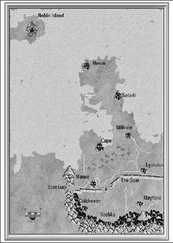

Then suddenly a strange thing happened. The beam of the searchlight on top of the water tower collided with another light. The yellow ray of the enemy searchlight.

The two powerful lamps pointed their jets of light straight at each other's eye, as if trying to dazzle the other to death.

Opposite loomed the disjointed forms of the mountains, lit by a garish reddish-purple glow.

The two beams of light remained locked in a furious embrace, piercing each other's eyes, bitter and stubborn, like knives poised for murder or like drunken lovers.

She looks up at the starry sky. Old queen Stella. The princess. The clapper of the bell. Gypsies. Him.

"Drive to Tiberias. To your fishermen. With me. Now."

"Are you out of your mind, Turquoise? Get out. Why did you get in? It's almost morning."

"I wish you dead, Ezra. I wish you'd drop dead. Right now."

Ezra tugs at his cap. His face is twisted in an expression of stupefaction. His mouth is set firmly. He does not know yet. His grandson is struggling to be born. He does not know. Noga does not know what she is saying.

"Get moving, I said. I said drive to Tiberias. Right now."

And after a moment's pause:

"I wish I were dead. You don't understand anything anything anything. You're so thick, great bear. What you've done to me. You don't care you don't care about anything great rough sweaty bear what you've done to me."

He looks at her. Tired. Reaches out to touch her cheek. Changes his mind. Starts the engine. Turns round to face back along the dead road. His face is blank. Numbly he squints at her and asks:

"You mean…?"

Noga does not answer. Ezra shakes his head a few times. In a furious undertone he says:

"No."

And again, after a silence, after a grinding of gears:

"What have I done to you?"

Turquoise suddenly gives an ugly laugh, fraught with something that is not laughter.

"Well? Shall we get married? It's usual to get married in such cases, isn't it?"

The man does not answer. His lower jaw drops, though, in what looks like a yawn, but isn't. His face in the dark wears a hangdog air. Noga looks. Sees. Still in the same tone that sounds like coarse laughter:

"Fool. Silly fool. You're a bad man. My father will kill you. My Rami will kill you."

Suddenly he brakes, steers to the edge of the road, lets go of the wheel, grabs her shoulders and plasters her face with rough kisses. Lets her go. Lights a cigarette. He starts driving again, slowly, as if the truck were heavily loaded. His head hunched into his shoulders.

Close to two o'clock, at the approach to the sleeping town, Noga was overcome by nausea. She put her head out of the window and vomited.

The air inside the restaurant smelled of smoke and grilled fish. The fishermen nodded to Ezra and his girl. They showed no sign of surprise. They did not exchange smiles. Abushdid himself in his stained apron approached their table and inquired how they would like their coffee. Ezra said that the girl would have the same kind of coffee as he drank. With cardamom.

Читать дальше