However that may be, Reuven's poems are not comical amusements for children. His children's verses, like all his poetry, present a poetic commentary on the world in simple language and appealing imagery.

Now we shall reveal a little secret. Indirect contacts have strangely been maintained between Reuven Harish and his divorced wife, between Eva Hamburger and her abandoned children. Isaac Hamburger's business partner is in correspondence with one of the members of our kibbutz, the truck driver Ezra Berger. Occasionally, Eva Hamburger adds a few lines in her sloping handwriting in the margins of his letters, such as:

It is four o'clock in the morning, and we have just got in from a very long journey through forests. The scenery here is very different from yours. The smells are different, too. Is it terribly hot there? Here it is cool and slightly damp, because of the northeast wind that blows at dawn. Could you send me, say, a napkin embroidered by my daughter? Please. Eva.

The gossip maintains that behind these snatched lines there lurks a warm affection. Our opinion is that they can be read in different ways, ranging from warm affection to cool indifference. There are those who firmly maintain that one or these aays Eva will return to the bosom of her family and her kibbutz, and that the signs are already apparent. Fruma Rominov, on the other hand, has been heard to remark that it would be better if Eva never came back. We used to think that Fruma said this out of malice. Now, on second thought, we are not so sure.

Reuven Harish, as we have said, has redoubled his love for his children. He is a father and also a mother to them. Sometimes, if you go into his room, you find him busy with wood and nails making a toy tractor for Gai or drawing pretty patterns on pieces of material for Noga to embroider.

He has also redoubled his ideological zeal. His serious poems, those that are not intended for children, emphasize the contrast between the mountains and the settled land. It is true that they are unpretentious, but they do display a faith in man's power to rule his destiny, and they are not mere versified slogans. If we approach them without preconceptions, we can find in them sadness, hope, and love of mankind. Anyone who scoffs at them betrays his own inadequacy.

The turbid torrent rushes into gloom:

Can man, so stunted, pitiful and weak,

Reach up to snatch a firebrand from the sun

And smile to see his fingers black and scorched?

Has he the strength to build a mighty dam

To stem the torrent and to tame the flood,

To leave behind him grim subservience

And paint his life a peaceful shade of green?

Reuven Harish throws himself wholeheartedly into his teaching, which endears him to his pupils. Even his dedication to the task of receiving the tourists is, when all is said and done — and leaving aside the malicious insinuations of the gossips — a sure sign of his devotion to the ideal.

The restrained poetry of his language, his intimate way of talking, the gentle pathos without a hint of insincerity, all these things endear Reuven Harish to us. A man of learning and at the same time a peasant, a man whose life has been enriched by suffering, Reuven Harish is one of our most remarkable men. And yet he has a certain simplicity. Not the simplicity of fools, but a clearly defined simplicity that is virtually a conscious principle. Let idle men of little faith mock him; we will mock them in return. Let them mock him to their petty, futile hearts' content. Mockery of him condemns itself and betrays the tediousness of the mocker, who will end up alone, bogged down in his own captiousness. Even death, about which for some reason Reuven has been thinking deeply today, ever since he saw the tourists off, even death will be more bitter for them than for him. They will face death empty and bare, whereas he will have left his slight mark on the world.

If only it was not for the loneliness.

The loneliness is agonizing. Every evening, after coming back from Bronka Berger's room, Reuven stands alone in. the middle of his own room, tall and thin as a youth, and stares in front of him with a surprised, insulted look on his face. His room is empty and silent. A bed, a wardrobe, a green table, a pile of exercise books, a yellow lamp, Gai's box of toys, some pale-blue pictures left behind by Eva, congealed bleakness. Slowly he undresses. Makes some tea. Eats a few biscuits. They taste dry. If his tiredness does not get the better of him, he peels some fruit and chews it without noticing its taste. He washes his face and dries himself on a rough towel, which he has forgotten to send to the laundry again. Gets into bed. Hollow silence. A wall light which is not fixed properly and will fall down on his head some night from force of gravity. The newspaper. The back page. A supplement devoted to problems of communication. Dear fellow citizens. The sounds of the night steal into the room. What day is it tomorrow? He turns the light out. A mosquito. He turns the light on. Mosquito vanishes. Turns the light off. Tuesday tomorrow. Mosquito. Finally, damp, uneasy sleep. He is tormented by nightmares. Even a pure man of sound principles cannot control his dreams.

We have dwelt so far on Reuven Harish's virtues. It is only right that we should also say something about his faults. Not to do so would be to neglect the right to judge, indeed, the obligation to judge, which, as we have said, is the secret of this place. But propriety and our sympathy for Reuven Harish combine to make us limit ourselves to mentioning one specific matter as briefly as possible, and indirectly.

A man in the prime of his life cannot go for long without a woman. Reuven Harish, who is exceptional in many other ways, is no exception to this rule.

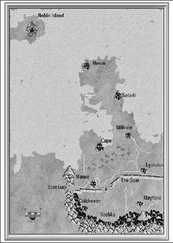

A platonic friendship had existed for some time between Reuven Harish and a colleague in the kibbutz school, Bronka Berger. Bronka, too, is one of the veterans of the kibbutz and was born in a town called Kovel on the Russian-Polish border. She is about forty-five, and so a few years younger than Reuven. If we were not aware of her good qualities we would say that she is plain. To her credit it must be said that she is a sensitive woman with strong intellectual leanings. What a pity that the friendship of the two teachers should not have remained pure. Some ten months after the flood — that is to say, after the upheaval of Eva's departure — gossip informed us that Bronka Berger had found her way into Reuven Harish's bed. We must stress our disapproval of this immoral affair, because Bronka Berger has a husband, Ezra Berger, the kibbutz truck driver. Ezra Berger is the brother of the celebrated Dr. Nehemiah Berger of Jerusalem. Furthermore, the object of Reuven Harish's affections is also the mother of two sons, the elder married and about to become a father, and the younger son is the same age as Noga Harish. So much for the negative side of Reuven's record.

***

We seem to have mentioned the names of the three Berger brothers already in passing. This was not how we ought to have introduced them. Since it has come about accidentally, let us take the introductions as made. Siegfried Zechariah Berger, the youngest of the three brothers, is the partner of the Hamburgers in the cabaret in Munich. Ezra Berger, a man of fifty or so, is the father of Tomer and Oren Geva, the deceived husband of an unfaithful wife. Dr. Nehemiah Berger, the eldest and most distinguished, is a scholar of modest reputation and lives in Jerusalem. If our memory does not deceive us, he researches into the history of Jewish socialism. He has already published a number of articles on the subject, and one day he will collect his scattered studies into a book that will contain all the sources of Jewish socialism from the time of those great reformers, the prophets, up to the establishment of the kibbutzim in the revived Israel.

Читать дальше