The winds might blast at two hundred miles an hour, the temperatures might drop to minus forty, but Thule Air Base stayed the same in the north, watching the sky, waiting for a threat. There were no desperate messages, crackling out to Washington. Thule Air Base was a piece of hi-tech military hardware, standing in the middle of the ancient ice. At Thule Air Base, they floodlit the winter, living it out in the gym, staving off lunacy with parties and concerts.

There was no Kurtz; the soldiers were the servants of a more elusive power. Thule Air Base took its orders from Washington; it was the northern outpost of a vast military empire. The invisible figures of the Pentagon controlled Thule from a distance, sending orders into the ice, which were obeyed without question. Everything was out of the hands of the majors, out of the hands of the soldiers scurrying through the blasting winds. The instructions were terse—sit in the north, watch the sky for threats to the USA. The ebullience wasn’t feigned; the soldiers liked the place, the glaciers and the rocks, the frozen ocean. But none of them knew what was going on. Far away, in the south, the generals were dictating the script. Sealed instructions, a sense of driving momentum, nothing could abate it.

WITH FAVORING WINDS, O’ER SUNLIT SEAS,

WE SAILED FOR THE HESPERIDES,

THE LAND WHERE GOLDEN APPLES GROW;

BUT THAT, AH! THAT WAS LONG AGO.

HOW FAR, SINCE THEN, THE OCEAN STREAMS

HAVE SWEPT US FROM THAT LAND OF DREAMS,

THAT LAND OF FICTION AND OF TRUTH,

THE LOST ATLANTIS OF OUR YOUTH! . . .

ULTIMA THULE. UTMOST ISLE!

HERE IN THY HARBORS FOR A WHILE

WE LOWER OUR SAILS; A WHILE WE REST

FROM THE UNENDING, ENDLESS QUEST.

“DEDICATION TO G. W . G.,”

HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW (1807-1882)

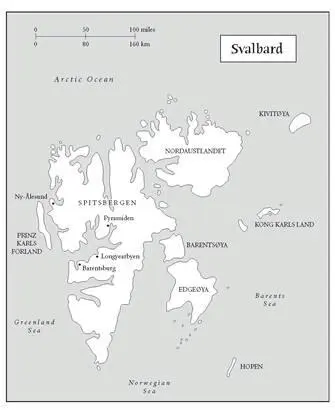

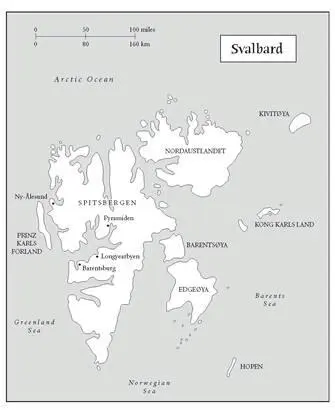

The plane flew into a beautiful northern night. The sun had set into the sea, and the sea was as calm as a mirror, reflecting the evening radiance of the sky. Below were the silent plains of ice, the blank spaces unseen for thousands of years. The darkening ocean, the drifting bergs, the sludge-ice beneath were blanketed in clouds and darkness. The flight had been chartered from southern Greenland to Svalbard; I was once again an interloper, having begged a seat from a tour company. It was a modern jet, comfortable and sterile. The cold sea stretched toward the Pole, as the ice began to close around the northern lands for the winter.

I had travelled in search of silence and a retreat from the city. I had been looking for a quiet and empty land, where everything would be simplified. I thought of it as a walk with Rousseau, disappearing out of the complexity of the city into the virtuous innocence of nature, experiencing a state of childish receptivity to external objects. It was a hunt for an Arcadia away from the seething world below. Yet I found history scattered across the plains and the urge towards rustic simplicity bound up with anti-democratic movements during the twentieth century, with the elitist agendas of the Thule Society. I had been retreating from all the clutter, the litter, until I was confronted with the whiteness at the most northerly edge of the retreat—the vast ice heart of Greenland. A land still magnificent and terrible, though polluted in places by military debris, controversially contaminated by lost nuclear materials. A land as close to absolute wilderness as I had found, still retaining the anarchic force of unbridled nature, even as the US Military sat out the winter on a patch of the coast.

When the remote north was an area of speculation and uncertainty, Thule could be many things. Thule could be pure while it was a fantasy, a place beyond the reach of humans. But now, the human history of the north in the twentieth century was bound up with my sense of Thule. As much as the silent ice and the ancient rocks, the mournful Inuit, the optimistic wilderness-hunters sitting on their slow boats to nowhere, and the US soldiers were a part of the history of the north in the last century. I had seen desperate bleakness, people struggling to survive. I had stared in horror at the silent ice. But amidst it all, I had felt moments of stubborn exhilaration. It was hard to know what to think. Where to stop, with the frozen ocean stretching beneath me?

Every society had some version of the yearning for an Arcadia, for a time when life was simple and everyone lived close to nature. My own entwining of this yearning with nostalgia for the simplicity of childhood was hardly unique. Growing older, growing up, brought all the chaos of adulthood, the pressures of money, the loss of time. Returning to London would bring back the feeling of disorder, loss of control. The state of innocence, the state of simplicity, was a holiday state, transient, impossible to sustain in the real world. As I listened to the low hum of the engines, I thought that knowledge and experience brought ambivalence; things became cloudy and difficult. Things might be better in a myth-world, but the option was not available. As an adult, I had to accept the trade-off—that the fall into experience brought a sense of comparison. It brought the consolations of knowledge, of knowing that others had felt the same way. The state of innocence was static—it lived and breathed and found fascination in small things, but it couldn’t choose. Having no knowledge of the alternatives, it couldn’t really understand.

The dream of Thule—a virginal untouched land—could never breathe and sweat as a crowded hopeless city or a history-strewn landscape could. Knowledge littered the landscape, changing everything, but it added a world of explorers and travellers and writers and poets to the empty rocks, as well as wars and violence and destruction.

It was easy to look nostalgically at the explorers, with their single goal, the emptiness around the North Pole. They had sailed, skied and flown, Nansen had set off in Fram , Amundsen had set off in the Norge , determined to discover, to shade in the blanks on the maps. It had driven them mad, this sense of something out of sight, something they didn’t know. Nansen had written it out in Farthest North —‘Why?’ he had asked. ‘Why did we continually return to the attack, to the land of darkness and cold, the shore of corpses. To what end?’ He answered his own question: ‘It was simply to satisfy humanity’s thirst for knowledge. Nowhere, in truth, has knowledge been purchased at a greater cost of privation and suffering. But the spirit of humanity will never rest till every spot of these regions has been trodden, till every enigma has been solved.’ The explorers would not settle for the fantasy version, the mythical imaginary version, the utopian version of the lands in the far north. Women with beards, unipeds, griffins and Hyperboreans were all very well, the explorers thought, but they wanted to find the real north, whatever it was. They were prepared to lose the old myths in order to discover what was really there. And Thule had changed, as part of this process. Thule had begun as a real place, but Pytheas’s account had been lost, and Thule had become a rich fantasy about the north, a word expressing a dream of remoteness and simplicity. Now the lands of the far north had been mapped, sometimes colonised, sometimes used for resources, sometimes for tourist retreats into the wilderness, Thule was something different. It contained imperfection and degradation within its borders. It expressed compromise and experience. Still, the longing for silent spaces, for the unusually empty, for the thrill of the solitary trail, continued to send people to the farthest reaches of the earth. The story would change and change again.

Читать дальше