My village was hardly a rustic idyll. It was more of a rustic commuter belt, a strip of suburbia disguised as villages and fields. The village feigned pastoral autonomy; there was a commune, which grew vegetables, and every year an Albion Fayre was set up on the fields around the village—stalls selling rosehip wine and home-baked cakes, to the soundtrack of Steeleye Span. People had boats on trailers parked in their drives through the winter, which they towed away to marinas for the summer. The daily momentum went towards London; each morning people stepped into their cars and commuted away, down the A12, arriving in the evening again. It was a compromise, too subtle for a child to understand. I saw only the winding lanes and the green banks of trees, the yellow ripeness of the corn, the blueness of the sky against the vivid fields. I knew nothing about the commuting files to London, cars moving bumper to bumper, hold-ups and jams, the tailbacks from Kelvedon to Capel St. Mary. I walked with my grandmother around the village as she pointed out the flowers in the hedgerows and made me listen to the different songs of birds.

I can’t remember when I first understood that there were worlds outside my village, places which moved to a pace of their own, irrespective of the seasons. My other set of grandparents lived on the Wirral, which supplied a holiday experience of somewhere else. These grandparents lived on a street opposite a bank of factories, in an interwar house. I remember staring through my grandparents’ kitchen window at a line of railings separating their road from the factory grounds. A broken umbrella had been hung on the railings, like a black rook, fluttering in the wind and the rain. The wind had blown piles of litter against the railings: cigarette packets with their shiny foil papers, crisp packets softened by rain, and lines of cans and bottles. My grandmother and I would sometimes take the bus into Birkenhead, sitting on the top floor staring at the traffic. There were days when we took the ferry to Liverpool, watching the churning wake and the gulls behind the boat. Liverpool would appear ahead, and I remember my grandparents telling me about the Liver Birds looking across the city, turned green by the weather.

I associated the Wirral with my grandparents specifically, as if it was their land, a land run under their rules, as distinct from those of my parents. This was why the houses were grey, and the umbrella rook hung from the railings, and why the factory had a gas container, shaped like an immense golf ball, which my grandfather said would take the whole of Merseyside with it should it ever explode. When I saw the golf ball, and the corrugated iron of the factory buildings, I knew I was near my grandparents’ house, and these decaying pieces of industrialism became a part of their world, serving only as signposts to their home, the final stage of a long journey. Everything in their house was novel: the shape and feel of the beds, the creak of the stairs, the smell of dust on the bars of the electric fire, the cupboard under the stairs, where my grandfather kept a World War Two flying suit. The cigarette lighter hidden under a model of Dick Turpin. The tins of barley sugars and mint imperials. The miniature forklift truck on a stand, which had been presented to my grandfather when he retired. The garage with the trapdoor, which opened onto steps going down to a shelter they had built during the war, tunnelled out under the garden. The urban environment was the exotic landscape of my grandparents’ lives, and of my mother’s past.

When I was ten, my parents moved to the Midlands, to a market town near Nottingham. It was the first time I remember disliking the view around me, noticing its plainness. The lines of interwar housing seemed limitless—buildings with ugly brick archways, hedges pruned into shapes, ornamental jugs and stools. The houses were crushed together, separated by brutal little walls, overgrown fir trees which looked like the fringes of graveyards. The surrounding countryside was undulating and forested, but I was too young to know what lay beyond the grey streets of our part of town. There was something tacky and bland about our house; the ceiling of my bedroom was covered with polystyrene, occasionally chunks would fall onto my bed, and I would cut them into shapes, the roof of the living room was flat, and fell to pieces one day. The garden was organized in neat rows, a fifties’ patio, rows of rhubarb plants, apple trees. I survived the transition, writing it out in a diary, quietly defiant: It is A.W.F.U.L., I wrote, a dozen times, across an entire day. The woods were too far away and I was never allowed to walk there. The only area worth spending time in, I had decided, was a field behind our house, a patch of grass which my brother and I shared with football teams on Saturdays, burly blokes shouting as they churned into the mud, sparse crowds cheering from the sidelines. One night, after staying for dinner at a friend’s house, I took a shortcut across the field, back to my parents’ house. The field was dark, muddy and uneven underfoot, and the stars were vivid in the sky. I stood for a while in the centre, furthest from the patches of light, looking at the shadows of the darkened grass, the ditches appearing as chasms in the darkness, the trees rustling gently. I was intrigued by the unfamiliar look of the field, the empty darkness, the quietness of the evening.

Because I never lived in the countryside again, I retained an image of the small Suffolk village, decked in the rich remembered colours of childhood, with the endlessly running soundtrack of the birdsong at dawn, the whirring of farmyard machinery. These memories were inevitably mingled with nostalgia, for the vivid sensations of early childhood, the blueness of the sky, bright yellow cornfields, the dim twilight of the winter evenings, when the streetlights became pale red at three in the afternoon. I idealized my childhood in the countryside, imagining it like a secret garden, remaining beautifully tended, should I ever return. In childhood, in the countryside, I had been free. At midnight when the house was quiet, I often thought of the village as I remembered it, the languid pace of the evenings, the slow rising of the sun across the fields.

AND WHEN THE MORN SHALL SPREAD WITH DAWNING DAY

HER PURPLE LOOM, AND SHOOT HER EARLY RAY,

YOU’LL THULE AND TH’ORCADIAN ISLES DESCRY

WHICH SCATTER’D O’ER THE OCEAN’S BOSOM LIE.

“KING ARTHUR,” SIR RICHARD BLACKMORE (1650-1729)

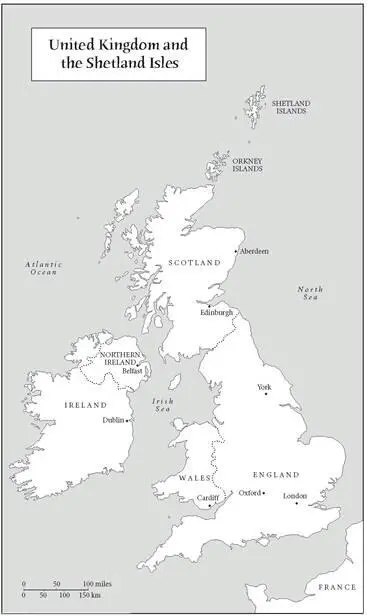

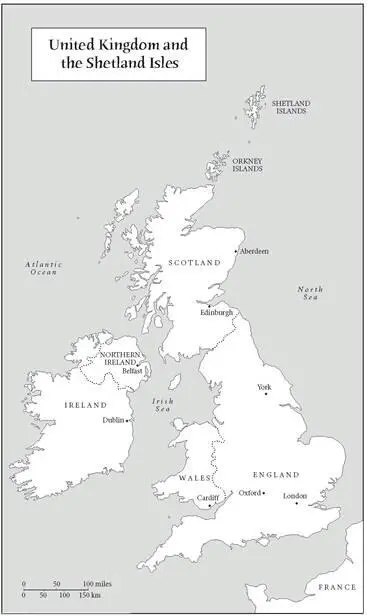

I flew back to London, and the next morning I was on the way to Scotland. Even at the time Nansen sailed north, even in Arne’s Golden Age, there was a holiday industry in remote and empty Thules. The British travellers of the nineteenth century worked their way along the British coast, heading first for Shetland, a former Thule, and then onwards to Iceland, another former Thule. There were fleets of tourist ships ploughing through the seas towards the north, taking their occupants away from their more cluttered countries. London lay under a thick coating of coal pollution, but the northern lands were pristine retreats for the city-sore. Richard Burton, British explorer, translator of the Arabian Nights , sailed along the British coast in 1872, carrying the idea of Thule like hand luggage. In the 1870s, William Morris—Socialist reformer and designer of tasteful patterns, who loved the Sagas—took the same route to the north. Anthony Trollope, author of baroque yarns, had sailed in a society horde, keeping to the main sights.

They were serious men, their beards spilling over their smart jackets, who all left England between 1870 and 1900, sounding the Thulian mantra, beguiled by the early stories of the far north. For them, even then, Thule was a metaphor for a receding world—an innocent world, where nature was unadulterated by human inventions, by the cranking pistons of industrialism. Everything was being dragged into the light, as technology moved relentlessly towards a world of rules and visible processes. But Thule remained—a place where the brute forces of the natural world were so unbridled that they threw up wild entertainments, inexplicable and extraordinary.

Читать дальше