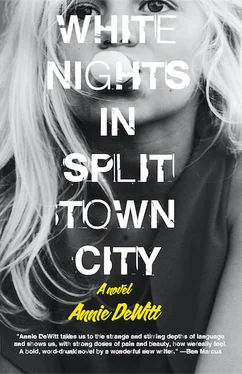

Annie DeWitt - White Nights in Split Town City

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Annie DeWitt - White Nights in Split Town City» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Tyrant Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:White Nights in Split Town City

- Автор:

- Издательство:Tyrant Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

White Nights in Split Town City: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «White Nights in Split Town City»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Annie DeWitt

Granta

Believer, Tin House, Guernica, Esquire, NOON

BOMB, Electric Literature

American Reader

Short: An International Anthology

Gigantic

Believer

White Nights in Split Town City — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «White Nights in Split Town City», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Mother was the first out of the Volvo. I recognized the tan of the windbreaker laying in the gutter to the side of the road. It was Wilson. “Don’t move, baby,” Mother said crouching down next to him. She patted the old man’s hair where it folded over his forehead. Mother’d had an accident once in a barn as a youngster. Her spine had ruptured on the concrete where she’d fallen out of the loft. “Don’t move her,” the man who owned the barn had said to her parents. For a few weeks she’d been in a body cast. Afterwards she’d walked off.

We waited silently by Wilson’s body until the ambulance came.

That night Margaret stayed with us. “He’ll be alright,” Mother said. “He’s a good boy.” Every few hours the phone rang. Callie called from the hospital with updates. “Observation,” she said. “There’s nothing we can do now but wait.”

Margaret sat in the club chair in our living room while Father smoked his cigars. Every now and again she got up and paced the room. She had the same blank face I’d seen on Father the morning I’d found him sitting there after Mother had left for the city. “Don’t stare,” Mother said to me, adjusting the afghan on Margaret’s shoulders.

For Margaret’s sake we went through the motions. “Blind drive,” Mother repeated, taking Margaret’s hand as she led her up the stairs to bed later that evening. “It could’ve happened to any one of us.”

Margaret passed the night with my parents. Mother made her a bed on the chaise that lined the far end of their room under the window.

I woke in the night to the phone ringing. Granny Olga answered it. After she hung up, she padded up the stairs in her slow heavy gait. She paused outside my parents’ room before she entered to collect her breath. I reached down between my legs to feel around for something to make me feel better. Something to make me land. All I felt was the sweat from the day and the nervousness.

Sometime later I needed to pee. As I crossed the hall, I stopped in front of my parents’ room. Their light was on. The door was open a crack. Margaret was standing on the deck where Father went out to do his screaming when he couldn’t sleep nights. He was standing there now beside her with his back turned. Margaret was in Mother’s arms. They had closed the slider so as not to wake us. Through the glass I could make out the outline of Margaret’s face as she covered it with a pillow and unleashed whatever it was she was needing to say.

In that moment, I felt Wilson’s presence rise up over the road. I imagined him as he had been in the barn that evening. “I’m gonna rake a girl,” he’d said, dancing in the dimly lit barn. Here was the moment, I thought, when all the knowledge the world had kept from him came rushing back into his body like the third eye I’d often heard Margaret speak to Mother about.

“What’s the difference between vision and a vision ?” Margaret had said, placing her fingers on her forehead and exhaling the breath in her body until she was empty, so empty she said she felt weightless until her chest rose up again and sucked the world back in.

I had seen Wilson’s face that night. His breath had steamed up the window despite the summer heat, Skeeter Davis’s “The End of the World” playing on the hi-fi in the background. “Just lie back,” I’d said. Or maybe Otto’d said, “Just look out the window.” When Wilson had knocked, I’d looked up at him. He’d waved. “Let him watch,” Otto had said.

Perhaps, I thought, this is what is meant by witness. The act of stealing something private from someone, something they otherwise would never have released into the world. As Margaret released her long, low scream, I thought I was free. I knew Wilson was no longer with us.

20

The roads that circled the town were hilly and lush. Occasionally on the bus when school resumed, we passed one of the old farmhouses with their acres of clear land traversed by long runs of post and fence. Windmills of painted pewter spun over the barns. Animals were once again let outdoors. If you closed your eyes to a slit and looked out the window you could follow the gradations of green as the landscape shifted. A short jaunt down the road was a single story prefab, the likes of which I’d seen the tractor trailer trucks deliver down the highway. The bikers who lived there had plowed a circular drive in front of the house to park their chrome. A line of roadsters littered the drive and the grove under the pine trees in front of the house. They’d hung an American flag out a window. Next was the junkyard where people brought the automobiles they’d driven to the ground.

Stacks of compacted cars towered around a two-door garage constructed of plywood and strips of corrugated metal. The sign out front advertised tires and parts. A pit bull ran the length of the barbwire that lined the yard each morning as we passed.

Granny Olga had seen me off the first morning. “Here,” she’d said pushing a small bag of wax paper into my hand before I’d boarded the bus. “One for each of your little friends.” She was standing on the porch, her hair still wet on the curlers. Around the thin ply of her nightgown she’d wrapped the old mink Mother kept in the closet in the hall, the one she’d bought in the city.

Halfway through our route, the bus came to a halt at the end of the hill which bottomed out into K’s drive. It had been some time since K had sat us. Since Mother’s return, she’d become just another of that summer’s passing apparitions. K descended from the steps of the salty Cape that morning just as I’d remembered her, leathered and floating. The small red door swung shut behind her. She paused mid-step in the middle of her parents’ plot. A look crossed her face. She pointed toward the wooden bridge that lined the brook where the water rose when the road washed out. A large tan form lumbered across it. In the beam of the bus’s headlights — the driver had been cautious in the mist — I could make out the faint glean of the animal’s coat. The body resembled a bobcat in grace and build. The thin grain of its fur pulled away from the muscle. There was something noble in its stagger. Its head hung, barely able to carry it’s own weight, and yet the animal continued forward despite the blood letting from the gash in its chest. From the scars and mud on its body, it looked as though it had traveled a great distance. Its torso was already weaving. Whatever had hit it had run.

As the bus came to a halt in front of K’s house, the animal collapsed in the gutter to the side of the road. The engine stalled. We stared out the windshield. After a moment, the driver swung open the door and descended the stairs. Her hand caught on the stick that started the wipers. The thin plastic blades screeched across the glass. I watched as the driver stooped over the body. The cat’s flanks were still heaving. A good deal of blood was gushing from its skull. She threw her jacket over its head. Before she went inside the house to place a call, the driver reascended the stairs of the bus in her shirtsleeves. Her face had paled. A blotchiness had risen on her neck. She gripped the steering wheel for a moment and peered down the aisle motioning us away from the windows. “Stay put,” she said.

K stood still on the lawn. The driver climbed toward the house at a waddle, the thicks of her thighs descending toward her knees, which seemed hardly to part. A few moments after she disappeared into the house a middle aged man in an old hound’s-tooth flannel came out. He went around back to fetch a shovel and a tarp.

The driver stood outside the bus smoking a cigarette as the man cleared the dog’s body from road. The road was narrow. It was impossible to skirt the remains. It took both of them just to lift the carcass onto the tarp. Afterwards, the driver picked her jacket up from the road with the end of a branch and tossed it into the gully. She said a few words to the man, climbed the stairs, and started the engine. As the bus pulled away, I peered out the emergency exit. The man dragged the carcass up the hill toward K’s house. He’d folded the tarp around the body, pulling it behind him like a sling.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «White Nights in Split Town City»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «White Nights in Split Town City» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «White Nights in Split Town City» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Элизабет Ленхард - Свидание со смертью[Date With Death]](/books/79651/elizabet-lenhard-svidanie-so-smertyu-date-with-dea-thumb.webp)