Michelle allowed the incomprehensible landscape to fuck with her mind. The round-backed cows became a sort of sea, she then allowed the sea, emerging beneath the cliffs, to become a menagerie, the lumps of trash beneath the pudding waves taking the shapes of animals she’d seen in books and magazines — a thick gorilla, a wide-eared elephant, the spindly neck of a giraffe. The waves drew back and heaved forward, the nauseated contractions of someone poisoned. Michelle saw real buses and airplanes, shopping carts and the roof of a home. An old telephone pole strung with gunk. She unfocused her eyes and they became dinosaurs, sea monsters. Broken boats bobbed, abandoned, looking like ghostly pirate ships. Perhaps some of them were. Across it all a web of oil stretched, like ebony lace or fishnet stockings.

I just can’t open my screenplay with a scene of myself smoking crack in Ziggy’s van, Michelle thought, and deleted twenty pages of text from her desktop. It felt like she’d deleted her stomach, something vanished in her body — well, that was rash. Too bad. The computer glared at her with its vacant cyclops eye, daring her to try again, to tell a universal story.

Michelle wracked her brain for successful books with prominent crack smokers. The A. M. Homes story where the suburban straight couple smokes it after the kids go away. Permanent Midnight , where the guy wrote for ALF but was really a total crackhead the whole time — that one got made into a movie, even.

What made those crack stories work? What made them, um, universal? Michelle suspected class. The suburbanites wanted to shake off the strangling yoke of prosperity and good behavior. Michelle imagined if the characters were black or gay the story wouldn’t work as well. The characters wouldn’t be able to risk it, their foothold on suburbia tenuous as it was. The reader was having a hard enough time trying to relate to a black person or a gay person without then having to relate to a crackhead. It was too much. Though black and gay suburbanites surely deserved a relaxing hit of crack cocaine more than the couple in the Homes story, they would have to settle for a glass of wine with dinner.

What about the television writer? Well, he was successful, that was crucial. People seemed to enjoy stories in which someone who Has It All almost Throws It All Away, but doesn’t. Redemption. For the crack narrative to succeed, the character has to be starting out on top, with a place to fall from. It can begin in suburbia or in the glass-walled office of a television executive. Readers anticipate the rungs descended. Crack wouldn’t work for Michelle’s character. She’s already sort of a loser, really broke, born that way. What the fuck is she doing smoking crack, the reader would want to know. Is she retarded? This is boring. I can read the newspaper for this. For Michelle’s story to be universal, it can only go in one direction, and crack does not further that trajectory.

All the writing had exhausted Michelle. She recalled Andy’s parting words, a curse, really— You better not ever write about me! — is that what she said? Michelle felt bound to it, though she had never agreed, never made such a promise. Still, it would be lousy of her to break Andy’s heart and then tell her secrets. It made Michelle’s stomach lump. She began a screenplay based on Quinn’s relationship with her husband. That was better — a lot of women had husbands. Very relatable. It could be a modern Belle de Jour , where the wife sneaks around with a downwardly spiraling lesbian, snorting heroin. She would have to make Quinn’s hair longer. She’d have to be girly for it to work. Otherwise she just seemed like some closeted lesbian married to a man who is maybe a closeted gay himself for having married such a manly woman. People would just be weirded out by that story. Not universal at all.

Michelle opened the film treatment with a shot of Quinn and her husband on the couch watching The X-Files . The husband idly played with Quinn’s long, luxurious hair. They fed each other popcorn. Michelle tried to imagine what they would say to one another and quickly became bored. Behind her, her knees on the scabby carpet, Quinn glanced at the screen as she packed her duffel bag.

I’d rather you didn’t write that, Quinn said. The story of my marriage. Her hands went up to her head and felt around her mop of messy curls, making sure they hadn’t morphed into ponytails. And why would you give me long hair? I have never had long hair. Not even when I was a kid.

Sorry! Michelle was a little defensive. I Was Trying To Make You More Universal. And Plus It’s Not Really You. She’s Based On You, But She’s Different.

I see she’s different, Quinn said. She has long hair. But that’s it. She has a husband who’s a glass blower, she works at an art museum, she’s having a heroin affair with a lesbian writer. The changed hair doesn’t do anything. It’s like you just wanted to humiliate me or something. If you’re going to write about me at least give me good hair.

Michelle turned back to her computer, feeling like a petulant child. Okay, she said. Fine. I Won’t Write About You. I Won’t Write About My Life Because No One Wants To Be In My Story. I Won’t Write About My Family Because They’re Fucking Over It. I Should Just Give Up And Get A Job At Taco Bell Then ’Cause This Is It, This Is All I Know How To Do, Write These Glorified Diary Entries And Now I Can’t Even Do That Because Everyone Is So Fucking Sensitive.

There was perhaps no way out for Michelle, not at this point. She had taken up documenting her own life with such vengeance, back when it seemed that vengeance was necessary. When she was angry at her moms for not having raised her better, noticed her genius or something, put her in a good school for chrissakes or at least an art program, anything to nurture her creativity, to acknowledge that she was creative at all, that they saw her. What good was having lesbian parents if they didn’t bring you to a goddamn art show?

While she railed against the women who birthed her, she decided, of course, to also rail against everyone who had ever slighted her as she trudged the landmine of childhood, adolescence. So many bullies and squares! So many heartbreakers! The heartbreakers continued into adulthood, and writing was a wonderful place to even the score. Michelle could express herself so wonderfully, her pain, their insensitivity. They would read her words and know that they had had this special, smart person in their arms and they had tossed them away, and they would forever regret it. They would never stop being sad.

There had never been a girl like Michelle in literature, of this she was sure. It tinged her writing with a bit of cosmic justice, which assuaged the icky feeling of self-obsession nicely. Someday she would be dead — as would all the people in her books, their petty problems evaporated — but this book would exist, the most holy object in the world, a book. All their dumb lives were elevated for it. Even a book like Michelle’s, a small book read by few. It didn’t matter. She had rendered them cinematic in their small lives. Really everyone should be grateful.

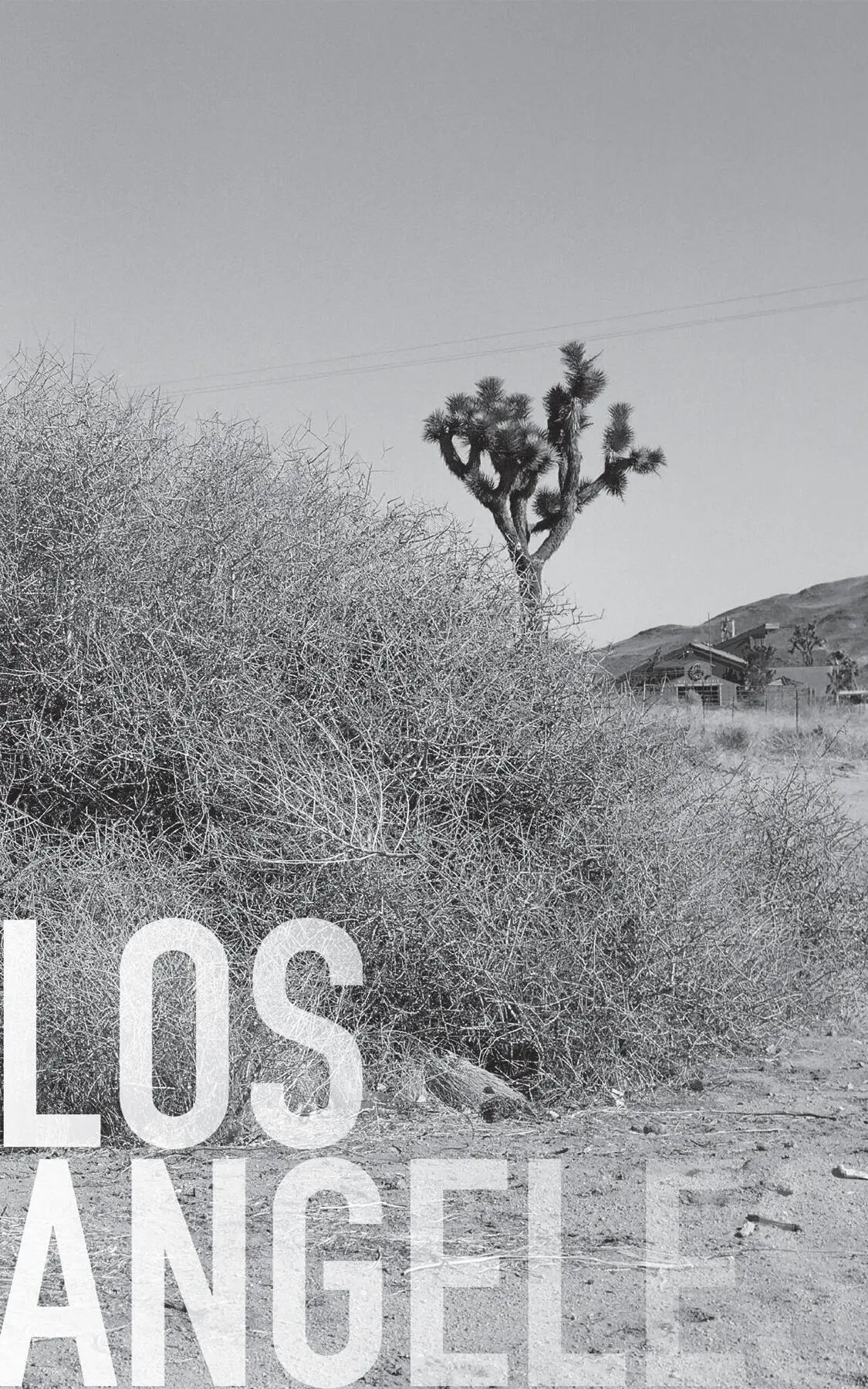

Except they weren’t. Quinn was only the latest to protest her inclusion in Michelle’s story — which, basically, felt like protesting their inclusion in Michelle’s life , which didn’t feel great, honestly, and besides, what were they doing there, then? But even this tantrum was but the last gasp of Michelle’s bravado. She’d grown weary of feeling like her writing hurt the people closest to her. She’d become more attuned to their feelings. She’d grown older and read wider and had begun to question how singular and important her story even was. Was she a war orphan, a refugee? No. She was a skinny, white, marginally attractive female living in the United States, where even poor people have MTV. What did she think was so important about her pain?

Читать дальше