A coffin open on a dais. I peer inside. It’s empty but for an oily stain slowly spreading across the bottom. Blacking the white satin. Quick, close the lid! Black tar bubbles out from the cracks and grooves and drips down into the grass and sinks into the earth.

Jacob where are you say something

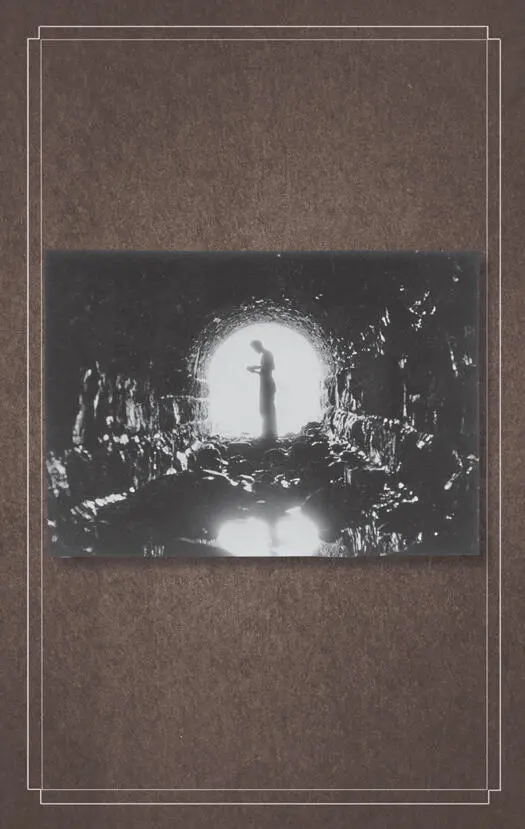

The headstone reads: ABRAHAM EZRA PORTMAN. And I’m tumbling into his open grave, darkness spinning up to swallow me, and I keep falling and it’s bottomless, and then I’m somewhere underground, alone and wandering through a thousand interconnecting tunnels, and I’m wandering and it’s cold, so cold I’m afraid my skin will freeze and my bones will splinter, and everywhere there are yellow eyes watching me from the dark.

I follow his voice. Yakob, come here. Don’t be afraid .

The tunnel angles upward and there’s light at the end, and standing at its mouth, calmly reading a book, is a young man. And he looks just like me, or almost like me, and maybe he is me, I think, but then he speaks, and it’s my grandfather’s voice. I have something to show you .

For a moment I jolted awake in the dark and knew I was dreaming, but I didn’t know where I was, only that I was not in bed anymore, not in the meeting hall with the others. I’d gone elsewhere and the room I was in was all black, with ice beneath me, my stomach writhing …

Jacob come here where are you

A voice from outside, down the hall—a real voice, not something from a dream.

And then I’m in the dream again, just outside the ropes of a boxing ring, and on the canvas, in the haze and lights, my grandfather faces off against a hollowgast.

They circle each other. My grandfather is young and nimble on his feet, stripped to the waist, a knife in one hand. The hollow is bent and twisted, its tongues waving in the air, open jaws dripping black on the mat. It whips out a tongue and my grandfather dodges it.

Don’t fight the pain, that’s the key , my grandfather says. It’s telling you something. Welcome it, let it speak to you. The pain says: Hello, I am not other than you; I am of the hollow, but I am you also .

The hollow whips at him again. My grandfather anticipates it, makes room in advance of the strike. Then the hollow strikes a third time, and my grandfather lashes out with his knife and the tip of the hollow’s black tongue falls to the mat, severed and jolting.

They are stupid creatures. Highly suggestible. Speak to them, Yakob . And my grandfather begins to speak, but not in English, nor Polish, nor any language I’ve heard outside my dreams. It’s like some guttural outgassing, the sounds made with something other than a throat or a mouth.

And the creature stops moving, merely swaying where it stands, seemingly hypnotized. Still speaking his frightening gibberish, my grandfather lowers his knife and creeps toward it. The closer he gets, the more docile the creature becomes, finally sinking down to the mat, on its knees. I think it’s about to close its eyes and go to sleep when suddenly the hollow breaks free of whatever spell my grandfather has cast over it, and it lashes out with all its tongues and impales my grandfather. As he falls, I leap over the ropes and run toward him, and the hollow slips away. My grandfather is on his back on the mat and I am kneeling by his side, my hand on his face, and he is whispering something to me, blood bubbling on his lips, so I bend closer to hear him. You are more than me, Yakob , he says. You are more than I ever was .

I can feel his heart slow. Hear it, somehow, until whole seconds elapse between beats. Then tens of seconds. And then …

Jacob where are you

I jolted awake again. Now there was light in the room. It was morning, just the blue beginning of it. I was kneeling on the ice in the half-filled room, and my hand wasn’t on my grandfather’s face but resting atop the trapped hollow’s skull, its slow, reptilian brain. Its eyes were open and looking at me, and I was looking right back. I see you .

“Jacob! What are you doing? I’ve been looking for you everywhere!”

It was Emma, frantic, out in the hall. “What are you doing?” she said again. She couldn’t see the hollow. Didn’t know it was there.

I took my hand away from its head, slid back from it. “I don’t know,” I said. “I think I was sleepwalking.”

“It doesn’t matter,” she said. “Come quick—Miss Peregrine’s about to change!”

* * *

Crowded into the little room were all the children and all the freaks from the sideshow, pale and nervous, pressed against the walls and crouched on the floor in a wide berth around the two ymbrynes, like gamblers in a backroom cockfight. Emma and I slipped in among them and huddled in a corner, eyes glued to the unfolding spectacle. The room was a mess: the rocking chair where Miss Wren had sat all night with Miss Peregrine was toppled on its side, the table of vials and beakers pushed roughly against the wall. Althea stood on top of it clutching a net on a pole, ready to wield it.

In the middle of the floor were Miss Wren and Miss Peregrine. Miss Wren was on her knees, and she had Miss Peregrine pinned to the floorboards, her hands in thick falconing gloves, sweating and chanting in Old Peculiar, while Miss Peregrine squawked and flailed with her talons. But no matter how hard Miss Peregrine thrashed, Miss Wren wouldn’t let go.

At some point in the night, Miss Wren’s gentle massage had turned into something resembling an interspecies pro-wrestling match crossed with an exorcism. The bird half of Miss Peregrine had so thoroughly dominated her nature that it was refusing to be driven away without a fight. Both ymbrynes had sustained minor injuries: Miss Peregrine’s feathers were everywhere, and Miss Wren had a long, bloody scratch running down one side of her face. It was a disturbing sight, and many of the children looked on with openmouthed shock. Wild-eyed and savage, the bird Miss Wren was grinding into the floor was one we hardly recognized. It seemed incredible that a fully restored Miss Peregrine of old might result from this violent display, but Althea kept smiling at us and giving us encouraging nods as if to say, Almost there, just a little more floor-grinding!

For such a frail old lady, Miss Wren was giving Miss Peregrine a pretty good clobbering. But then the bird jabbed at Miss Wren with her beak and Miss Wren’s grasp slipped, and with a big flap of her wings Miss Peregrine nearly escaped from her hands. The children reacted with shouts and gasps. But Miss Wren was quick, and she leapt up and managed to catch Miss Peregrine by her hind leg and thump her down against the floorboards again, which made the children gasp even louder. We weren’t used to seeing our ymbryne treated like this, and Bronwyn actually had to stop Hugh from rushing into the fight to protect her.

Both ymbrynes seemed profoundly exhausted now, but Miss Peregrine more so; I could see her strength failing. Her human nature seemed to be winning out over her bird nature.

“Come on, Miss Wren!” Bronwyn cried.

“You can do it, Miss Wren!” called Horace. “Bring her back to us!”

“Please!” said Althea. “We require absolute silence.”

After a long time, Miss Peregrine quit struggling and lay on the ground with her wings splayed, gasping for air, feathered chest heaving. Miss Wren took her hands off the bird and sat back on her haunches.

“It’s about to happen,” she said, “and when it does, I don’t want any of you to rush over here grabbing at her. Your ymbryne will likely be very confused, and I want the first face she sees and voice she hears to be mine. I’ll need to explain to her what’s happened.” And then she clasped her hands to her chest and murmured, “Come back to us, Alma. Come on, sister. Come back to us.”

Читать дальше