She gently swept the silky hair off of his high forehead, and the gesture of tenderness made her feel tender. Now she knew where that auburn hair came from. Redheadedness ran rampant in New Walden.

She shouldn’t wake him. She herself would have snarled like a trodden cat if she was woken in the middle of the night because somebody with something to tell her couldn’t control himself until the morning. But she couldn’t control herself.

“Wake up, you crazy Valdener Hasid,” she whispered in his ear. “Let me tell you about your next Rebbe.”

XIV The Argument from Inconsolable Solitude

Something jolts Cass into wakefulness at 2 a.m., and he can’t get himself back to sleep. He had conked out early, falling into a deep and dreamless sleep, but now he’s fully awake, groping around for provocations for feeling guilty, because that’s the normal behavior when you wake up in the middle of the night. You wake, you feel guilty, you search for reasons to justify your guilt. Anyway, that’s normal behavior for Cass.

It could be Shimmy Baumzer. Shimmy had served the salmon over guilt. The president had exacted a promise from him to think about “what sort of goodies you might like to see in a retention package.

“For example, I notice that you don’t own your own house but rent a place in Cambridge. I could call up the Comptroller’s Office right now, my friend,” and he gestured with his elegant hand toward the phone, “and have them cut you a check that would cover the down payment for a house in Weedham. Maybe even in Cambridge. Another idea for you to kick over is whether you’d like to have your own Center for the Psychology of Religion, with a discretionary fund at your disposal. I can be creative, Cass. Just promise me you’ll give it some thought.”

Could it be around Lucinda that his unease is congealing? Yes, definitely. He’s been holding back on her, not sharing the news about his offer from Harvard, and that’s a troubling thought in the middle of the night.

His conversation with her tonight had been brief. She had been anxious to go through her PowerPoint one more time before getting her seven and a half hours of sleep. Rishi Chandrakar, the unworthy keynote speaker, had been mentioned again.

This isn’t easy for her. She’s such a proud person, in the best sense of the word. She had lifted up her transformed face to Cass in the twilight as he held the door of Katzenbaum open for her, and she had laid bare her vulnerability. She had been so terribly betrayed, both by the despicable David Prentiss Cuthbert, chairman of Princeton’s Psychology Department, and by the system, and she’s still bruised and uncertain, though nobody but he knows. Mona, for example, for whom his affection has cooled, hasn’t a clue. Mona is very hard on Lucinda. Lucinda is right that she provokes irrational responses from envious people. It’s obviously ludicrous to complain of being both brilliant and beautiful, and of course Lucinda isn’t complaining, even when she sounds as if she is, but, still, she’s been hurt by the people she calls griefers. His darling girl! He wishes he could be more helpful, but she’s so beyond him. What can he say that will give her what she needs? He keeps trying.

“The first time I gave a talk at one of Pappa’s conferences, he told me that if it had been any better he would have had to shoot me,” she had told him tonight on the phone, sounding both proud and sad at the same time.

“Well, then, please don’t make it any better this time,” he’d responded, which at least had made her laugh.

The textbooks for his self-tutorial in game theory are piled up on his night table, and he decides to use his sleeplessness to make some more progress toward understanding the Mandelbaum Equilibrium. The farther he gets in the textbooks, the more he’s been enjoying his foray into her science, finding himself increasingly resorting to its form of reasoning in order to clarify things for himself. The first thing to figure out always is whether a situation is a zero-sum game or not. Sum games are the ones where what’s up for grabs-say, some pot of money-stays constant, and zero-sum games are the kind in which one person’s gain is another person’s loss: the addition of all the players’ winnings add up to zero. You win, I lose; I win, you lose.

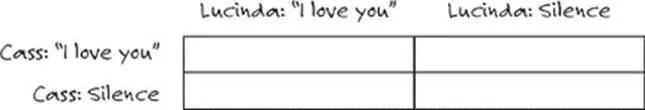

All sorts of situations can be analyzed as games, whether zero-sum or not. Take love, for example. Let’s say you’ve got two people in a romantic relationship and neither has said “I love you.”

Let’s call them X and Y.

No, let’s call them Cass and Lucinda.

What are the risks and what are the possible benefits of one of them saying “I love you” first?

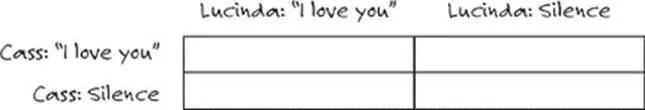

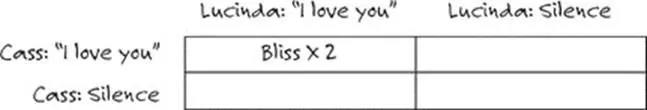

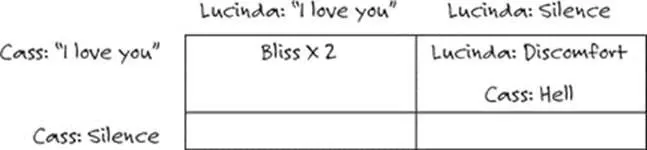

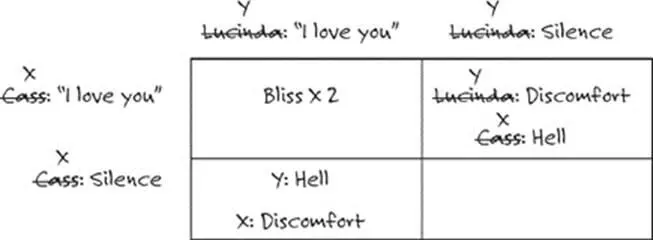

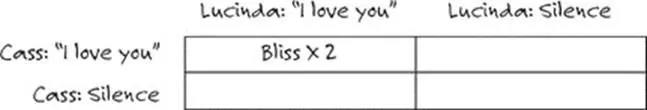

Cass grabs a pen from Lucinda’s night table, and, using the inside of the cover of one of the texts as his sketch pad, he draws himself some boxes:

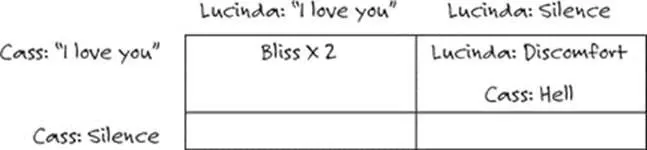

If Cass were to say “I love you” and Lucinda responded “I love you,” which is what the top box on the left represents, then there would be a huge payoff. For Cass there would be bliss, and, presumably, for Lucinda there would be bliss as well, so the result would be bliss times two.

But what if Cass said “I love you” and Lucinda didn’t reciprocate? That would probably result in some degree of discomfort for Lucinda, and a huge loss for Cass, especially if Lucinda was discomfited enough to decide to move out: they had both agreed that the arrangement was experimental.

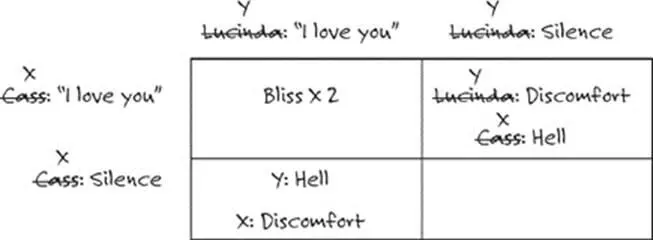

Cass supposes he has, for the sake of thoroughness, to fill in the box in which the situation is reversed, the lower box on the left, with Lucinda confessing her love and Cass keeping silent, even though he knows that this square exists only in the realm of the purely theoretical. Still, they call it game theory , don’t they? Better call them X and Y.

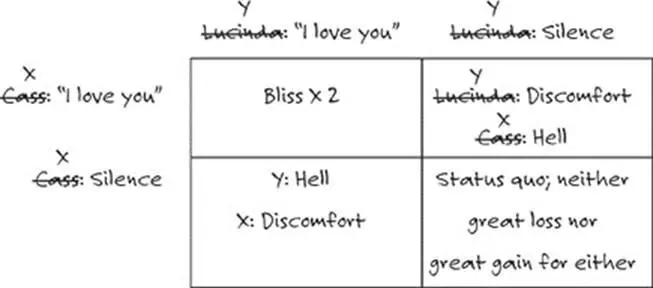

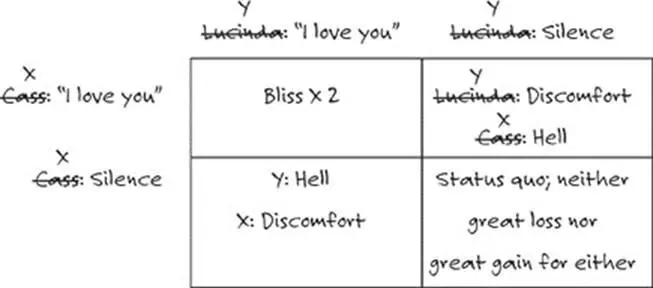

The last box is the one in which neither of them said “I love you.” That is the status quo.

So now how is Cass supposed to figure out from these boxes the rational thing to do?

If he says, “I love you,” then, considering the situation only from his own point of view, there is possible bliss but also possible hell, which, he supposes, cancel each other out. If he doesn’t say “I love you,” there is neither bliss nor hell to be gained. He will maintain the present situation, which is certainly a positive one for him-not as positive as bliss, of course, but definitely positive. It seems as if it is rational to keep silent- so rational, in fact, that he wonders why anyone would ever risk saying “I love you” first, which is a bit of a paradox.

Perhaps the lesson to be learned is that it isn’t always sensible to be rational.

Or perhaps the Bliss × 2 that can possibly result if a lover speaks out his love is so hugely positive that it blows all the other boxes out of the water. Could that explain why anyone dares to say “I love you” first?

And here’s another thought: If he shows Lucinda his little grid, it would be a way of indirectly saying “I love you” without taking the risk of saying the actual words. If Lucinda wants to accept his reasoning as a way of saying “I love you” and reciprocate, then they will keep the huge payoff of the first box on the left: Bliss × 2. But if she doesn’t want to reciprocate, then he won’t have blurted out an indiscretion that can’t be taken back. They can keep up their present relationship, maintaining the imperfect-but-preferable-to-nothing status quo. So, by indirectly saying “I love you,” Cass, or X, can possibly get the biggest payoff without risking the biggest payout.

Читать дальше