“Dr. Foster’s office.”

“Hello, Gordon?”

“Hello.”

“Is there anybody there? Can you talk?”

“There’s no one here.”

“Why haven’t I seen you? Is there anything the matter, Gordon?”

“I couldn’t get away,” Gordon said wearily. “Ever since the business about the fifty-dollar check, the assumption is that I’m an insane gambler and not to be trusted even to go for a walk alone.”

“You sound so bitter.”

“I don’t mean to. Are you all right, Ruby?”

“Naturally.”

“Did you find a place to move to?”

“Not yet. When will I see you, Gordon?”

“God knows. When I can think up a new lie, I guess.”

“I’ll be waiting tonight after I get through work.”

“No, don’t. I can’t — I can’t stand the thought of you just sitting there in that place waiting for me. You don’t understand — I feel as if I’ve got to be there and yet I can’t get there. It tears me apart, I can’t tell you — I—”

“I won’t wait if you don’t want me to,” Ruby said quickly.

“Do you understand? Just for one night I want to feel that I don’t have to be two places at once, that no one’s expecting anything of me. I know, I guess this sounds childish, but just for this one night I’ve got to be a free agent. Don’t you ever feel like that, Ruby?”

“No. I don’t want to be a free agent. I like to wait for you, even if you don’t come. What else would I do if I didn’t wait for you?”

She hung up, and for a minute she sat staring listlessly into the round black mouth of the telephone. What else would. I do if I didn’t wait for Gordon?

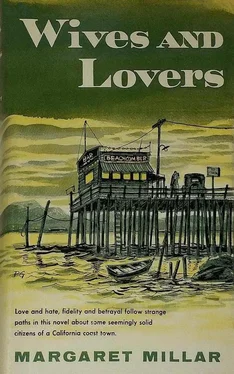

That night after work she walked to the edge of the wharf and stood with her forearms resting on the rail, watching the lights of the town. The lights flickered halfway up the mountain so that the town seemed to be pinned to the side of the mountain with stars. On the wharf the lights were going out one by one. Everyone was leaving, except the customers in the bar. The kitchen was closed, and the waitresses and the kitchen help were departing, in twos and threes. They walked quickly, on the balls of their feet so their heels wouldn’t catch in the gaps between the planks. They were all anxious to get back on the dry land since it was common talk that the wharf was heading for disintegration and no one was doing anything to stop it. Occasionally some haphazard repair work was done and a few of the rotting piles were replaced, but this did not mitigate the sense of imminent doom among the people who worked at the Beachcomber. This feeling was nurtured by the cashier, a woman called Virginia, who had escaped certain death for five years now, six nights a week. To newcomers like Ruby, Virginia was careful to point out that the wharf was nearly eighty years old, and aside from the natural deterioration of the years there was also the strong possibility of a bad storm or a tidal wave.

“Mark my words,” Virginia said. “One of these days we’ll all find ourselves in the ocean hanging onto anything that floats. And you know what I’m going to do then? I’m going to sue them! I’m going to sue the whole damn bunch of them, the owners of the wharf and the city that grants the franchise and Anderson and his outfit, and when I collect I’m going to retire, build a house in the middle of the desert and live the life of Riley. Maybe we could all sue them and all of us retire.”

The hired help of the Beachcomber were drawn together, by Virginia’s enthusiasm, into a common dread and a common dream. The life of Riley appealed to them, and those among them who couldn’t swim found themselves eyeing the furnishings of the Beachcomber with the quality of buoyancy in mind.

When Virginia saw Ruby leaning against the railing she paused a moment to proffer advice. She reminded Ruby that the railing was nearly eighty years old, that it was quite a drop into the sea, and the water was cold and deep. Moreover if Ruby drowned she couldn’t even sue anybody, being dead.

Having survived one more day, Virginia sped back to land.

Ruby leaned her full weight on the railing. I wouldn’t care, she thought. I wouldn’t care about drowning except I wouldn’t like the water to be very cold. Gordon might be sorry for a while but he’d be glad too. He wouldn’t have to think or worry about me any more, he wouldn’t have to feel obliged to me all the time. It would be a relief to him if I died.

She began walking slowly toward shore. She wondered which of the lights of the town belonged to Gordon and what he was doing. Reading? Or perhaps he was already asleep? Poor Gordon. She hadn’t meant to cause him so much trouble. Everything had seemed very harmless and right to her in the beginning. All she wanted was to be in the same town as Gordon and to see him now and then. It wasn’t a great deal to ask for, but she hadn’t foreseen how even this much might affect Gordon’s life. Instead of making him happy she had only made him despise himself, and her too. There was no way that she could give back to Gordon his dignity and self-respect. Nothing could dissolve the feeling of degradation that Gordon had had the night he dampened his hair under the tap in the public lavatory. He had told her about it, and Ruby understood his rage and humiliation and guilt. He had said, “I can’t stand it,” and she believed now that this was true. Gordon was destroying himself and she was the instrument of destruction.

She groped blindly toward the lights of the town, wishing the wharf would rot away under her feet. She seemed to feel it actually moving, not rolling gently with the swell of the water, but throbbing with quick shivers like an old man with palsy. The headlights of a car beamed suddenly behind her. She stepped aside, and as the car passed her, the planks of the wharf rattled and shuddered. She began to run, as fast as she could, toward the shore.

When she reached the boulevard the car was parked along the curb waiting for her. She recognized Mr. Anderson at the wheel but she pretended she didn’t see him.

He called after her, “Hop in and I’ll give you a lift home.”

She stopped, shaking her head. “No, no thanks.”

“Might as well.”

“It’s such a nice night, I don’t mind walking.”

“You look tired.” He opened the front door of the car. “Come on, get in.”

She got in, holding the fox fur tight around her throat.

“You don’t have to act so scared,” George said. “I assure you I’m pretty tired myself.” He was smiling, but there was a note of irritation in his voice. “I’m going to have a beer and a steak sandwich. If you want to come with me, fine. If you don’t, I’ll take you home first.”

“I’ll — just get out any place and walk home.”

“That suits me.” He started the car and headed up Main Street. “You’re a funny girl. I can’t make you out.”

She said nothing. She was not interested in Mr. Anderson’s opinion of her. She hardly considered him a human being, he was so remote from her thoughts.

“I’m sorry I had to speak a little rough to you about that bar check,” George said. “But I’m in business, and if I want to stay in business I have to shoot off my mouth once in a while.”

“I didn’t mind.”

“Good.”

“I’ll get off at the next corner, if that’s all right with you.”

“Well, it isn’t, but there’s not much I can do about it, is there?”

At the next corner he stopped the car. He leaned across her to open the door. She shrank back against the seat to avoid his touch.

George said dryly, “Is there something the matter with me or is there something the matter with you? You’re not married or anything, are you?”

Читать дальше