You can’t hurry love, as the song goes. You can’t hurry grief, either.

I have this idea that he did what others before him have been known to do: convinced himself that those he left behind would be all right. We’d be in shock for a while, and then we’d grieve for a while, and then we’d get over it, as people do. The world doesn’t end, life always moves on, and we too would move on, doing whatever we had to do.

And if that’s what he had to do in order not to suffer, on top of everything else, the pain of guilt, that’s all right with me. That’s all right with me.

Sure I worried that writing about it might be a mistake. You write a thing down because you’re hoping to get a hold on it. You write about experiences partly to understand what they mean, partly not to lose them to time. To oblivion. But there’s always the danger of the opposite happening. Losing the memory of the experience itself to the memory of writing about it. Like people whose memories of places they’ve traveled to are in fact only memories of the pictures they took there. In the end, writing and photography probably destroy more of the past than they ever preserve of it. So it could happen: by writing about someone lost—or even just talking too much about them—you might be burying them for good.

The thing is, even now, I still can’t say for certain whether or not I was in love with him. I’ve been in love no few times, and never any doubt about it. But him— Well, what does it matter now. Who can say. What is love? It’s like a mystic’s attempt to define faith that I remember reading somewhere: It’s not this, it’s not that. It’s like this, but it’s not this. It’s like that, but it’s not that.

But it’s not true that nothing’s changed. Not that I’d use words like healing or recovery or closure , but I am aware of something different. Something that feels like a preparation, maybe. Not there yet but on the verge of some release. A letting go.

Text message: How are you? Your apt now shipshape!

My hero.

Now I’m thinking about the woman whose house this is. Was. A woman I’ve never met. Except for the bare essentials, the three little rooms have been cleared out. Left behind, probably by mistake: a silver-framed black-and-white photograph hanging on the bedroom wall. A couple, no doubt she and her husband, standing by a car. (Why did people back then always pose for pictures standing by a car?) He in his US Army uniform, she in the style of the day: big shoulders, victory rolls, Minnie Mouse pumps. Handsome/pretty. Young. Just kids. I know that he died more than a decade ago. It seems she’d been managing very well alone until last year, when everything started failing at once. From an energetic swimmer and gardener and crack crossword-puzzle solver she’s become all but helpless. No legs, no eyes, no ears, no teeth, no wind. Almost no memory. Less and less mind.

When did she plant the roses. In full magnificent bloom now, the red and the white. A fragrance to make you go, Aaah . I think how much they must have pleased her, year after year, and made her proud. And it’s not the thought that she must miss them, but that she’s no longer capable of missing them, that makes me sad. What we miss—what we lose and what we mourn—isn’t it this that makes us who, deep down, we truly are. To say nothing of what we wanted in life but never got to have.

Definitely true past a certain age. And that age younger than people might like to think.

I see the sun has knocked you out. But let’s not overdo it, eh. It’s supposed to go up to ninety today.

Maybe I should get you some water. And while I’m at it a nice tall glass of iced tea for myself.

Oh, look at that. Butterflies. A whole swarm of them, floating like a small white cloud across the lawn. I don’t think I’ve ever seen so many flying together like that, though it’s not unusual to see them in pairs. Cabbage whites, I think. Too far to tell if there are black dots on the wings.

They should watch out for you, o eater of insects. One snap of those jaws would take out most of them. But there they go, heading right for you, as if you were no more than a giant rock lying in the grass. They shower you like confetti, and you—not a twitch!

Oh, what a sound. What could that gull have seen to make it cry out like that?

The butterflies are in the air again, moving off, in the direction of the shore.

I want to call your name, but the word dies in my throat.

Oh, my friend, my friend!

Thank you, Joy Harris. Thank you, Sarah McGrath.

I am also grateful to the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, the Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts, and Hedgebrook for their generous support.

An excerpt of this book appeared in The Paris Review . Thank you, Lorin Stein.

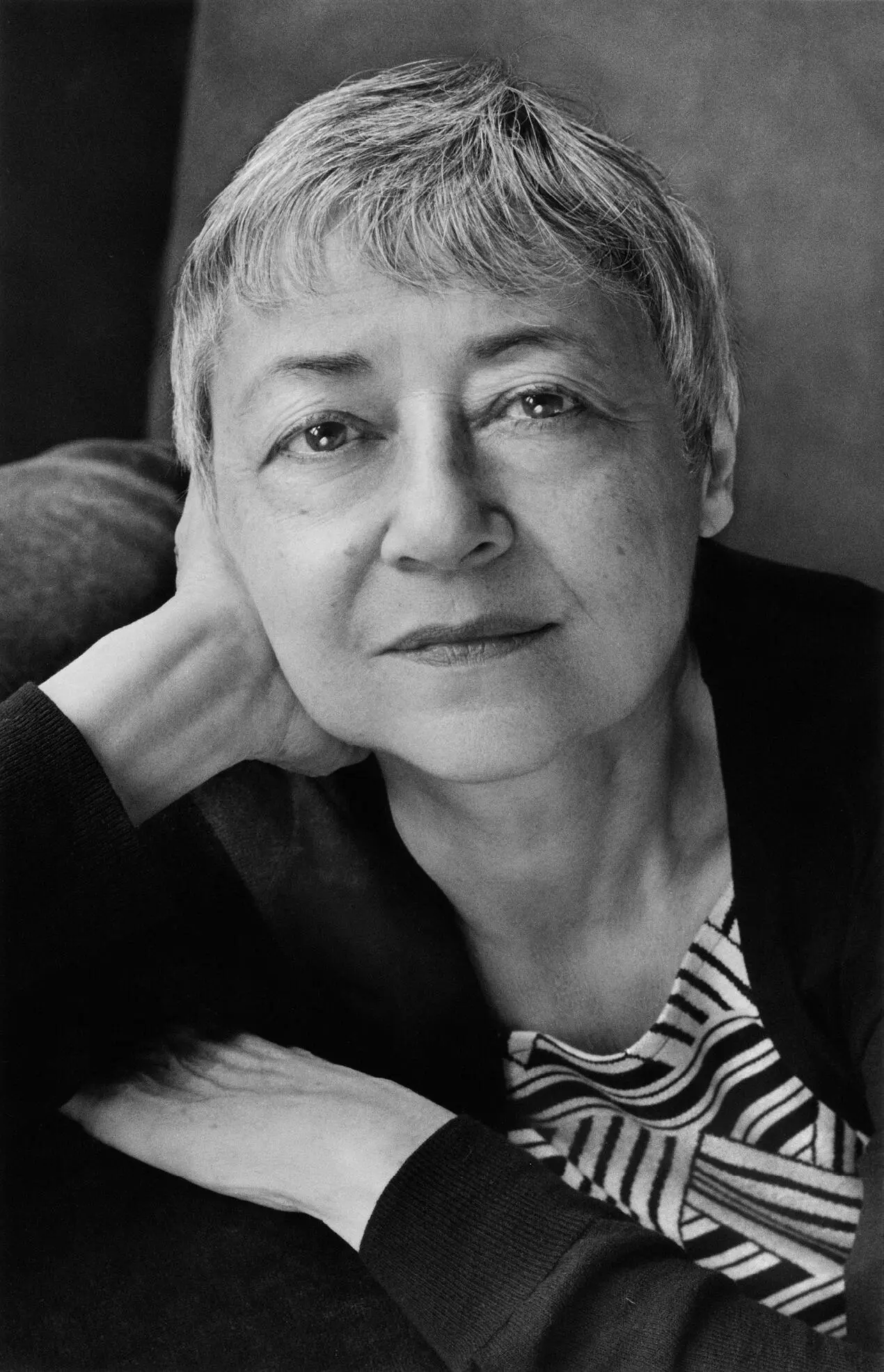

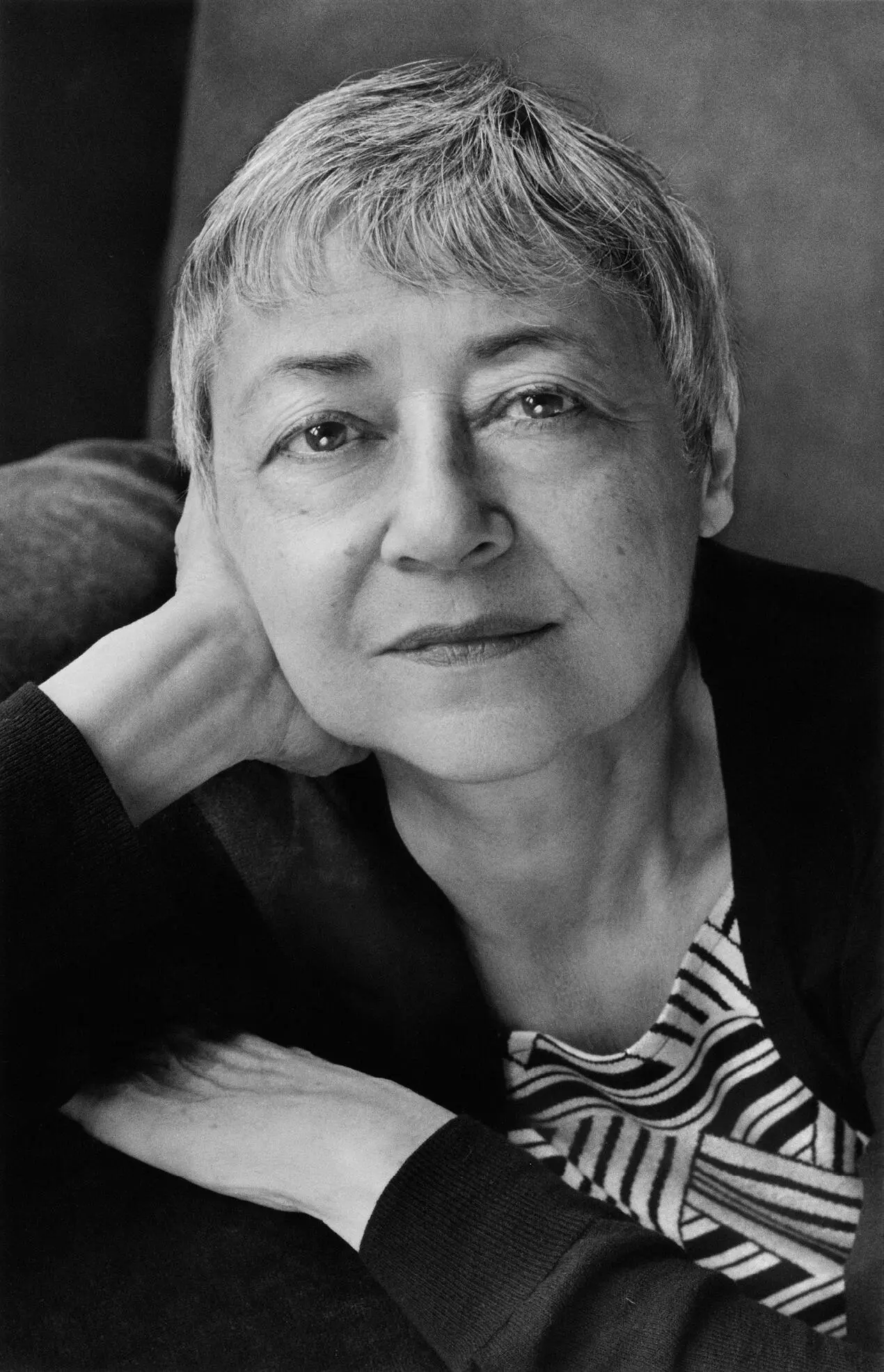

© Marion Ettlinger

Sigrid Nunezis the author of the novels Salvation City , The Last of Her Kind , A Feather on the Breath of God , and For Rouenna , among others. She is also the author of Sempre Susan: A Memoir of Susan Sontag . She has been the recipient of several awards, including a Whiting Award, the Rome Prize in Literature, and a Berlin Prize Fellowship. Nunez lives in New York City.

sigridnunez.com

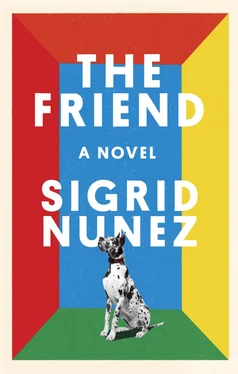

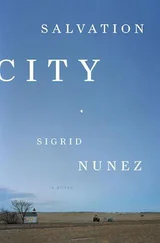

Also by Sigrid Nunez

A Feather on the Breath of God

Naked Sleeper

Mitz: The Marmoset of Bloomsbury

For Rouenna

The Last of Her Kind

Salvation City

Sempre Susan: A Memoir of Susan Sontag