Not that the neighbors were too upset about old Um Elias, who had made a living selling miserly amounts of watered-down alcohol to them, but nevertheless they came as a body and spat at the young man in question, barely twenty years old, as he was forced into a police car. The police took him to the apartment in Rukneddine where he’d hidden the stolen goods in a well next to the graveyard. His two accomplices lived in the same building, and they didn’t try to flee but surrendered and confessed in full. The following morning the three criminals were quietly brought before an examining magistrate. He was frustrated, as the crime of murder no longer called for such caution and care, and the criminals’ easy confession increased his irritation. They would all find a way to avoid prison anyhow, the easiest route being to accept a position among the murderers of the regime militias, though there was always the chance that the resistance might storm the prison, knock down the walls, and destroy their files regardless.

In recent months, when people died, no one bothered asking after the hows and the whys. They already knew the answers all too well: bombings, torture during detention, kidnappings, a sniper’s bullet, a battle. As for dying of grief, for example, or being let down by your body, deaths like that were rare—and no one lamented a death that didn’t have any outrage attached to it.

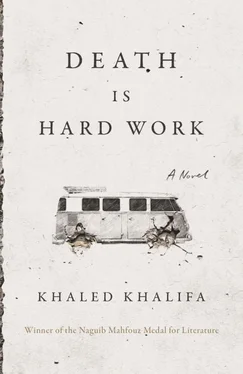

Before Bolbol and his siblings left Damascus, he had called his office and requested a leave of absence. He received the indifferent condolences of his colleagues over the phone and asked that no one take the trouble of condoling with him in person, or indeed trouble themselves with helping him arrange the burial. He was still feeling the same deeply rooted fury as when the young doctor on duty told him his father’s heart had stopped. If his father had died three months earlier, when he was still in the village of S, then everything would have been easy. The cemeteries there were large and plentiful, and any one of the people still living in the town could have buried him with all the consideration due to the great and illustrious ustadh , their comrade in revolution from its first day to his last. They would have considered him a martyr. Bolbol’s only responsibility would have been to hear about it—and then pass along word to Hussein and Fatima and spread the news by calling their few relatives still in Anabiya, some of whom would certainly have supported Bolbol to carry out his duty of looking mournful and organizing a small ʿaza for a few close friends. But that body lying on its hospital bed, and the glances of the on-call doctor—they only made Bolbol feel trapped. Death had become hard work. Just as hard as living, in Bolbol’s view.

The doctor had instructed the orderlies to cover Abdel Latif’s face and carry him to the morgue, and then asked Bolbol to sign for the body and get it off the premises before the following afternoon. If not, they would be forced to deal with it themselves. Priority in the overcrowded hospital morgue was given to the bodies of soldiers.

When he used to think about it, Bolbol hadn’t reckoned on his father’s death being such a disaster for him. He had half hoped that if Abdel Latif needed to die nearby, it would be somewhere closed off by a siege or while Bolbol was traveling far away. In such a case, he would have been absolved from the duty of arranging everything, and responsibility for his father’s last wish would have had to be shouldered by Hussein, who wouldn’t have hesitated to ignore it.

One night, three days before Abdel Latif died, Bolbol took his father to the hospital after his pains grew worse. It was lucky they stumbled across a taxi by the all-night fuul restaurant. Finding a driver willing to cross the city from east to west, not to mention finding a vacant bed in the public hospital, was such a stroke of luck that God should have received their utmost thanks—and Bolbol really did do his best to feel grateful. He gave the taxi driver the fare he had requested plus a tip for helping his father onto a stretcher; he insisted on staying with Bolbol until he was assured that Abdel Latif wouldn’t get abandoned by the hospital staff in some corridor. Then again, the driver, too, probably preferred to be in the hospital than on the dangerous streets at night. Bolbol didn’t ask him why he didn’t go home; he was afraid of the answer. On an earlier occasion, trying to make small talk in a taxi, he had been unwise enough to ask the driver when his shift was over and he could go home, but the driver had sneered and described his house in Zamalka in detail, including the fact that it had been bombed and his wife lay dead beneath the rubble. In the end he had asked Bolbol, “So what home do you mean, sir?”

For months, Bolbol had avoided talking to anyone he didn’t know or even leaving the house. Going outside was hard work. He was content to travel back and forth from work and read state newspapers ostentatiously on the bus. On his days off, he watched black-and-white Egyptian films on cable and grieved for this golden bygone era. He didn’t know why he put himself through this, but at least this was a pastime that no one could possibly find suspicious; everyone was mourning for the beautiful days that they’d lost. Longer holidays such as Eid he spent making different types of pickles. He liked the new strategies he’d developed in order to keep himself sane, even though they were all strictly short-term arrangements. He didn’t dare acknowledge that his life was a collection of trivial acts that would sooner or later have to come to an end.

One day, his isolation was punctured. One of his father’s neighbors’ sons—an engineering student turned combatant in the Free Syrian Army—called Bolbol and informed him that his father’s health made it very difficult for him to remain in the besieged village. Bolbol couldn’t bring himself to say anything in reply—not out of shock from hearing about his father’s deterioration, but from fear of being arrested for speaking to a person who lived in S. The caller didn’t have a lot of time and said that they had been fortunate enough to manage to smuggle the ustadh out to the abandoned gas station at the edge of the village. He asked Bolbol to arrive at six o’clock that evening to take him away.

The call had come at three in the afternoon. Bolbol couldn’t chance saying a word to this person calling from an unknown number. What if the line was tapped? He was absolutely certain that the regime monitored every word coming out of the village. He had to think of a way out of this terrible mistake. Suddenly one of his rare bursts of self-assurance led him to decide to resolve the matter. He thought he would call Hussein. His brother should help in a situation like this. He dialed Hussein’s number and was overcome with frustration when he heard that phone service had been temporarily interrupted. There was still time, though. Hussein would probably get back to him when he saw the missed call. Bolbol sat in a neighborhood restaurant in Saruja and asked for beans and rice. He contemplated what he was about to do to himself: his father was going to come and live with him in his small house. Well, maybe his father wouldn’t be able to endure being in a district loyal to the regime.

Bolbol had worked hard to gain the trust of his neighborhood. The details on his identity card marked him out for suspicion; for four years now, similar details had spelled catastrophe for many others. Thousands of people disappeared without a trace, simply for being born in areas controlled by the opposition, just as many regime supporters had disappeared in those same areas. Kidnappings, ransoms, and random arrests were widespread and tit-for-tat responses meant they only escalated in frequency. People’s movements were tightly controlled. Any error could be very costly.

Читать дальше