As he listened to his father go on and on about Nevine, his town, and his revolution, Bolbol could only assume that he was making it all up. It wasn’t possible for a man in his seventies and a woman over sixty, the mother of two martyrs, no less, to chase through meadows after butterflies and write each other love letters as if they were separated by a great distance; equally, it was impossible to sit in the sights of a never-ending military bombardment and yet spend hours talking about the moon. But, then again, he could hardly call his father a liar.

In those moments, Abdel Latif had wanted to tell Bolbol that he was no longer a lonely old man in need of care; he hadn’t been toppled; he had regained his former vitality, and all at once. He reflected on his life without anger, he entertained no illusions, nor did he let himself get carried away. In this, father and son were much alike: Bolbol understood the truth of his own life, too, in those days—that he had changed considerably, and that the solitude whose merits he discussed with Abdel Latif wasn’t so terrible. He still remembered how his name had changed from Nabil to Bolbol; Lamia began to call him Bolbol as a pet name, and in the early days of his solitary life he had liked hearing others use the same name that Lamia used. His original name was almost completely forgotten at this point. Whenever Bolbol saw it on official documents, he felt it belonged to someone else. “Bolbol” sounded lighter and more human to him, whereas “Nabil” suggested some well-adjusted man still dreaming of a grand future. Recently, Bolbol had lost even the impulse to dream and make plans; carrying out his father’s last wish was an exercise of what little remained of his will. After all, you have to do something if you aren’t just going to lie down and die—if you don’t want to sink down to the center of the earth.

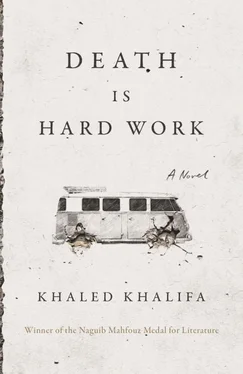

The corpse swaying to and fro in the minibus was the only truth he had left. He still thought of it as a real person, a collection of tangible, worldly sensations: it could do things; it wasn’t just a gelatinous lump. It had a family, and that family still had a long way to go, and on the journey maybe they might even talk like real siblings again.

They traveled fifty kilometers in four hours. Agents at three checkpoints were relatively patient with the family when they saw the bloated body. The third checkpoint allowed them to pass using the lane reserved for military use only, and hope was revived that they might reach Anabiya before evening. Along the road, the signs of battles were clearly visible: damaged tanks, burned-out cars, dried bloodstains. The houses by the road were destroyed and abandoned, and other houses in the distance seemed to have been scorched. Very few people and animals moved through the streets of the small semi-abandoned villages; the only visible morning activities were death and exodus. A double-cab pickup passed them on the road, filled with soldiers armed to the teeth. They flagged down the minibus and the other cars and ordered them to stop and clear the road for a line of tanks. The people in the stopped cars avoided looking at the long convoy. Hussein approached a car driven by a man in his sixties, traveling with his wife and a daughter, who looked around thirteen. A Pullman coach stopped behind them, taking passengers to Aleppo, some of whom got out to smoke. Hussein joined them to chat, waving his hand at Bolbol and Fatima and nodding along with whatever the passengers were saying. It was the very picture of people brought together by tragedy, far from home, trying to dismiss their fear by making small talk.

The tank convoy was still passing when planes swooped overhead. The drivers and their passengers watched the planes bomb some place invisible from this vantage point, and the sound those bombs made gave the strong impression that death was even more imminent than usual. The line of vehicles and their marooned passengers reflected that it was useless to try to resist death. Everyone surrendered to what was to come; no one thought of running away. Where would they go? Hussein came back to the minibus as everyone tried to stick together or else find somewhere to hide; very few were still wandering around bored and smoking. The minutes of horror eventually passed, the airplanes left, and silence descended on the vast wilderness. The final military vehicle accompanying the line of tanks signaled that it was all right for the civilians to continue, so long as none of them overtook the convoy.

It was now almost one o’clock; reaching Anabiya before sunset again seemed a lost cause. Most of the idling cars pulled out all at once; of course, every one of the travelers wanted to reach their destinations before nightfall. After five kilometers, however, they all had to stop again; the cars that had tried to overtake the rest reappeared, and their drivers signaled to everyone that they couldn’t go forward. Volleys of bullets could be heard nearby, behind a hill only a few kilometers away.

Bolbol considered their predicament. Once again, where would they go? There was nowhere but here, out in the open. They stopped the minibus by one of the big passenger coaches, and some other cars stopped close to them. They all stood there for an hour or two. Then the sound of gunfire stopped, and news passed among the vehicles that a battalion of guerrillas had attacked the line of tanks and had now retreated to their original positions. The tanks had been diverted onto the military road leading to the villages south of Aleppo. Six tanks from the convoy were burned out; one of them contained the remnants of a dead man that his comrades had left as food for wild animals.

It was the only corpse visible. Smoke was still rising from the rest of the destroyed tanks. Bolbol thought of this body and dreaded Hussein seeing it, in case it led him to play that same old broken record he’d been spinning since they left home: that bodies weren’t important in war, loved ones could make do with a torn shirt or a severed leg wrapped in a shroud inside a closed coffin… Many families had buried their loved ones without once laying eyes on the horrifying sight of their dismembered corpses.

Bolbol knew that if his father weren’t a cadaver, he would be going on and on about all the features of the area. He would be telling his children the names of the local villages, would be listing the flora and fauna, the produce the region was famed for, even its precise elevation above sea level. It had been his favorite hobby, to explain the geography of each district he passed through, but a corpse couldn’t do any of that.

Evening began to fall. Reaching Anabiya before midnight was out of the question. Bolbol convinced himself that everything would be easy once they reached Aleppo; only forty kilometers separated Aleppo and Anabiya, and they would travel that distance easily, especially as they were from the area and belonged to a well-known family. His father, who had fled his family more than forty-five years earlier, would nonetheless be saved by its name. Bolbol shared his optimism with Hussein and Fatima, but was discomfited by their silence. Hussein was wondering despairingly, But when will we reach Aleppo? Fatima’s frightened face made it plain to the others that their predicament, stuck on a half-impassable road crossing abandoned villages and boundless wilderness, wouldn’t be an easy one to escape. Hussein was now convinced that patience was the only thing that might save them, and he no longer suggested burying the body by the side of the road or in one of the graveyards belonging to these small villages. (He had pointed out that they could always come back after a time to retrieve it—no one would steal a stranger’s body—but, then, bodies won’t wait: they soon rot and melt into the earth.)

Читать дальше