Olga Slavnikova

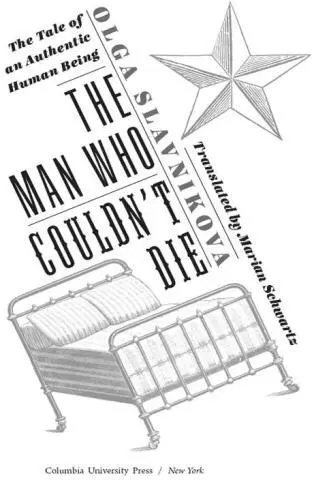

THE MAN WHO COULDN’T DIE

THE TALE OF AN AUTHENTIC HUMAN BEING

INTRODUCTION

Ressentiment Monsters

MARK LIPOVETSKY

Imet Olga Slavnikova in 1987 or 1988. Back then we both lived in Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg); she worked as an editor at Ural , the local “thick” and respectable literary magazine, and I was publishing my first articles in it. She had just finished a journalism degree at Ural State University (my alma mater too) and was launching her literary career, both as a prose writer (her first novella, A Freshman Girl , was published in 1988) and as a literary critic. We had many common interests—primarily the culture wars that were roaring around us—and quickly recognized each other as like-minded. The circle of young literati to which we belonged was mesmerized by the newly discovered continent of Russian underground and émigré modernist and postmodernist literature—from Vladimir Nabokov to Sasha Sokolov and Venedikt Erofeev—which started to appear in print after decades of censorship and about which we talked all the time.

This was the peak of perestroika, and Olga was an active participant in the literary innovations of the time. One such innovation was a “special” issue of Ural (1988, no. 1), which published a few pieces of nonconformist prose and avant-gardist poetry along with a radical (for the time) political-economic article. Although it was the latter that brought national recognition to this issue (according to rumors, it was resold on the black market at a vastly inflated price), Ural continued to publish less conventional literature in a “magazine within a magazine” entitled Text , with a belatedly Structuralist chic. Although not entirely independent from Ural ’s management, Text published exciting prose and poetry by young and not-so-young writers who would otherwise never have appeared on the pages of any Soviet journal. The novelty of this literature was not political, it was aesthetic—most of the works published in Text not only deviated from Socialist Realism (which nobody took seriously anyway) but also disregarded social realism and the classical realist canon—which in the eyes of readers and the literary establishment was a much greater sin than being anticommunist.

At that time, however, nobody yet saw Slavnikova as a leader of the new literature from the Urals (or from Ural ). This changed drastically after her first major novel, A Dragonfly Enlarged to the Size of a Dog (1997). Published in Ural , it was included on the short list for the Russian Booker Prize. Furthermore, A Dragonfly became the year’s greatest literary sensation—critics and readers alike noticed the novel and praised it as one of the brightest debuts of our generation. This was the work where Slavnikova found her original style. Valentin Lukianin, a critic and editor-in-chief of Ural in the 1980s and 1990s, aptly writes:

Everybody knows that a photo of the head belonging to a fly, mosquito, or dragonfly, when taken through a microscope, reveals a horrible and even fantastic monster. But this monster really exists, although we don’t recognize it in a small insect. In the same manner, Slavnikova placed normal and ordinary relations between intimates under a microscopic lens, and through this device, she discovered everyday Russian reality from such an angle that nobody has ever experienced. [1] Valentin Lukianin, “Ural”: zhurnal i sud’by (Ekaterinburg: Kabinetntyi uchenyi, 2018), 530.

Slavnikova’s newfound style paradoxically fused the lessons of traditional realism and radical modernism. On the one hand, Slavnikova is attentive to the everyday life of poor and socially marginalized people, especially women. On the other, she enlarges the details of their ordinary existence with such a powerful “microscope” that they turn into surreal symbols, and through this metamorphosis her prose exposes life’s frequently morbid undercurrent. This approach, however, excludes a necessary component of the Russian literary tradition, the writer’s compassion for her characters. Slavnikova is truly mesmerized by her monstrous “everyday people,” but with the fascination of a scientist, she keeps her narrative distance, never allowing readers to identify with any of her characters. Her “coldness” stands for an unblinking analytical position, for an acidic skepticism hostile to any sweet illusions. Such a distancing is critical for all her works, but especially for The Man Who Couldn’t Die .

Almost all of Slavnikova’s subsequent novels would gain recognition and win literary prizes—the new style discovered in A Dragonfly proved flexible enough to absorb diverse themes and stories, all invariably associated with contemporary Russia. Her subsequent novel, Alone in the Mirror (1999), written while she still lived in Ekaterinburg, appeared in the prestigious Moscow journal Novyi Mir and won its award for the best publication of the year; her slightly dystopian 2017 (2006, translated into English by Marian Schwartz in 2012), which Slavnikova wrote after her move from Ekaterinburg to Moscow, received the Russian Booker Prize. Two of her latest novels— Light-Headed (2010, translated into English by Andrew Bromfield in 2015) and Long Jump (2018)—were both short-listed for the largest Russian literary prize, The Big Book, and the latter still has a chance to win it. The only exception is the novel that you are holding in your hands, The Man Who Couldn’t Die (or The Deathless in Russian), which first appeared in 2001, in the Moscow magazine October . Although it didn’t win any major literary awards, many critics consider it Slavnikova’s best and most accomplished work of literature—her true masterpiece.

Furthermore, The Man Who Couldn’t Die has a cloud of a scandal around it—and what could be better? Slavnikova claimed that the authors of the famous German film Good Bye, Lenin! (2003) plagiarized her plot. Both works juxtapose dramatic scenes of early postsocialist transition with the figure of an immobile elderly person—the paralyzed grandfather, a former wartime scout, in Slavnikova’s novel, and the comatose mother, a former Party activist, in Wolfgang Becker‘s film. In both works, relatives try to protect their weak-hearted elders from the shock of the revolution and its consequences by maintaining the illusion that things are the same as before in the USSR and GDR, respectively. To support this illusion, both Slavnikova’s and Becker’s characters produce fake newsreels for home TV.

Frankly, I don’t share Slavnikova’s concerns: I believe that the metaphor juxtaposing physical immobility and being stuck in the past and/or awakening in a different country was too obvious to anybody living through the postsocialist transition not to become a common trope. Furthermore, the radical differences between The Man Who Couldn’t Die and Good Bye, Lenin! are much more significant than their similarities. The latter is full of optimism and excitement around the long-awaited revolution, which is why the film became so popular worldwide, while Slavnikova’s novel tangibly delivers a sense of bitter disappointment—of what Nietzsche called ressentiment —in the fruits of the same revolution.

The concept of ressentiment—inferiority and weakness compensated for through hostility toward others, be it the authorities, immigrants, liberals, or Americans—has been frequently used to describe the situation in post-Soviet Russia. In the words of the philosopher and cultural historian Mikhail Iampolsky,

Читать дальше