“Ask her yourself. Her shift starts at ten.”

We stood in a far corner of the parking lot, near the dumpsters and the back door to the hotel kitchen, propped open to let in the mild night air. I could hear the clatter of pots and pans, the rat-a-tat of a knife chopping, the tinny radio and shouted Spanish. The night manager crossed her arms, waiting for us to begin.

“You might remember a group of guests who stayed here a while ago,” Jamie said. “Five rooms, reserved by Danner Pharmaceuticals. They had dinner in the restaurant.”

“We’ve got 206 beds in this hotel,” she said. “Average length of stay is one night. And you’re talking about how long ago, so you do the math.”

“Maybe it’s unlikely,” I said, “but if you recall anything—”

She waved a hand. “Relax. I remember. Jesus, how could I forget?”

There had been noise issues, she said. A guest had called the front desk to complain about shouting and raised voices. The first time the night manager knocked on the door, it settled down for a while. Then it started back up, and it was worse. The guest next door said she could hear loud thumps, something shattering. Sobbing and screaming.

The manager went back upstairs, this time with a security guard in tow. She passed a man in the hallway. He was sweaty and out of breath, his shirt unbuttoned and flapping open, but she had no cause to stop him in that moment—he was a guest, after all.

When she reached the room, the girl was alone. She had two black eyes, a broken arm. Bruises around her throat, blood dripping from her nose. The doctor had already gotten a taxi and was long gone. The night manager wanted to call the police, but the girl insisted that George could just drive her to the emergency room. She was okay, she said. She’d drunk too much and tripped over the furniture. She was clumsy like that.

“He tried to pay me off,” she said. “That kid, George. His hands were shaking like crazy. Here was five hundred dollars for the cleaning fee, he said. The cleaning fee! Give me a break. I did have to replace the carpeting in that room, by the way. Her blood was everywhere. No way to get the stains out.”

“So you didn’t take the money,” Jamie said.

“Take a bribe from a jackass like that? No way. He let this girl get beat to a pulp and then pretended like all she had was a bump on her forehead. The Danner guys don’t stay here anymore.” She grimaced. “Too ashamed to show their faces.”

AFTER THE BREAKTHROUGH, Eliza assigned two more producers and a handful of assistants to the story. But even with added resources, so much of our reporting hinged on serendipity. An assistant had a friend at Bayer who had heard about unfair tactics at their rival. Another producer knew a guy who had once dated a girl who worked at Danner, a very pretty girl who carried Gucci handbags and leased a BMW and didn’t know a thing about pharmaceuticals.

For my part, I was working on the woman from the hotel. George had finally gotten hold of her new number. She called herself Willow, and now lived in Florida. She was skittish and unpredictable, responding to texts but not phone calls, Facebook messages but not e-mails, vanishing for long stretches of time. Jamie offered to try speaking with her, but I felt protective. If she wanted to live far away, with a new name and a new identity, starting over—who could blame her?

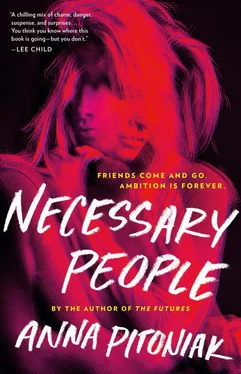

A story like this, Eliza explained, was delicate. It took a long time to convince sources to go on the record. If our competitors heard what KCN was working on, they might try to scoop us. For that reason, Eliza insisted we keep the circle small. “I don’t want some intern spilling the beans at happy hour,” she said. “Only tell the necessary people.”

Stella still didn’t know what the story was, but she no longer seemed to care. In August, she anchored the Saturday morning news program while the regular host was on vacation. A year into her work as a reporter, it was becoming obvious that the KCN executives had bigger plans for her. Her assignments got better, and she was no longer on the morning shift. She appeared on shows across the network, often in prime time. Our lobby was lined with larger-than-life posters of Rebecca Carter and her ilk: the chief White House correspondent, the morning show anchors, the Peabody-winning investigative reporter. The bona fide stars of the network. A few weeks after Stella’s first turn in the anchor chair, her poster went up in the lobby. Stella, with a royal purple sheath dress and shiny blond hair, arms crossed and gaze serious, with the KCN tagline, The News You Need.

In the past, at least Stella had the grace to behave with self-awareness. When she vacationed in Gstaad and St. Barts, she downplayed the glamour. When men competed to buy her drinks, she dismissed them as shallow and dumb. Even just last year, when she and Jamie started dating, she broke the news conscientiously. Stella always made an effort to bridge the socioeconomic and aesthetic gulf that separated us.

And why did she do this? Because she needed me. Because I was loyal. Because I was the only person who gave her the steadfast attention she craved. Because she was most alive when she had an audience, and I made her feel alive. Who else could see past her vanity, her temper tantrums, her mood swings, and give her what she needed in order to feel like herself? She had to make those efforts, because if she were to alienate me completely, who would she have left?

Well, I’ll tell you who. The most loyal audience there is: viewers of cable news.

“A toast,” Thomas said, lifting his glass. The six of us—the Bradley family plus Jamie and me—were seated around their dining table on a Sunday evening in October. Thomas glowed with the pride of a parent whose once-problematic child has, by succeeding unexpectedly, erased every painful memory of the past. “To our Stella.”

“We’re so proud of you, sweetheart,” Anne said.

Stella smiled. “Don’t forget the best part, Daddy. We won the demo last week.”

“Like winning a beauty pageant judged by a blind man,” Jamie said quietly.

“Oh?” I whispered. “You mean eighteen- to forty-nine-year-olds aren’t flocking to cable news in droves at 9 a.m. on Saturdays?”

“What are you two talking about?” Stella said. “You know it’s rude to whisper, Violet.”

“Nothing.” I lifted my glass. “Just toasting to you.”

It was chilly for October, and there was a blazing fire in the dining room fireplace. So many meals like this had peppered my years of friendship with Stella: the finely embroidered napkins, the heirloom silver, the distinctive taste of oregano in the roasted Cornish game hen. The world could change, years could pass, but there would always be these constants. Thomas often boasted of how his Bradley ancestors fought in the Revolutionary War. And, really, how different was this life from that of his ancestors? Strip away the changing technologies and fashions, and what remained was the comfort and the power of wealth. And especially the endurance of wealth: the system we lived in produced certain victors, and pointed to those victors as proof of its own efficacy. Just look at Stella.

“You must hear all sorts of buzz about Stella,” Anne said, looking at me as she cut her food into small pieces. “Ginny tells me she’s really putting her mark on the place.”

“Of course,” I said. “Although I’ve been a bit distracted lately. It’s been busy.”

“Violet’s being modest,” Jamie said. “She’s working on a big story.”

My cheeks grew hot. A year into their relationship and he still hadn’t learned how to avoid pissing Stella off. “We’ll see if it turns into anything,” I said.

Читать дальше