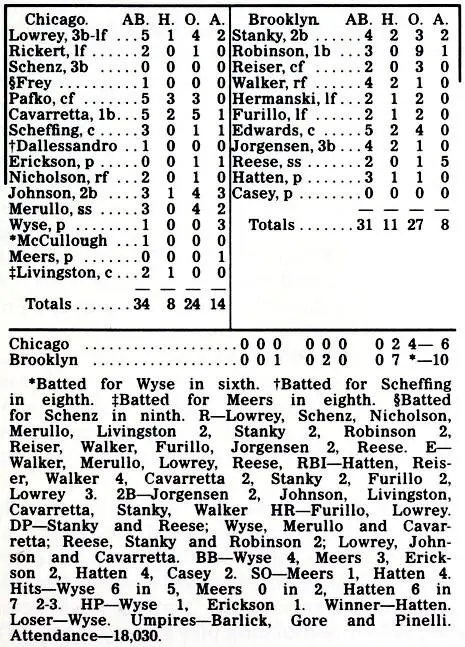

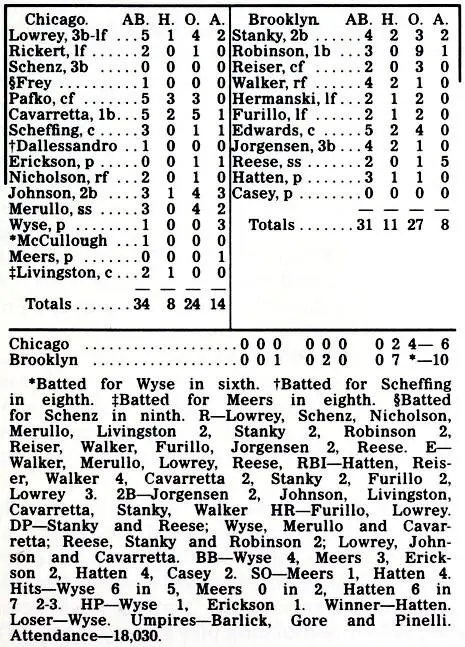

Box Score 2

I played first base on the junior high school team and hit .303 that year, though the averages were sometimes suspect because the fifth-grade teacher was our scorekeeper and she gave everyone a hit who reached base. No one ever reached on an error. The school supplied the uniforms, grayish woolens with blue numbers. They had to be worn by a new player after you left, so they were of a generic size, and tended to bag. The school also issued the catcher’s mitt and the first baseman’s mitt. It was a claw, a three-fingered glove with the fingers laced together.

While I listened to the Dodgers games, I usually kept a scorecard, and, when my father came home from work, I would share it with him. It never occurred to me that he would be less interested than I, and, in fact, if he was, he never said.

If I missed a game, I could listen, usually with my father on the screened front porch, at seven in the evening, to a fifteen-minute recreation of the game, complete with sound effects and an announcer, it might have been Ward Wilson, simulating play by play. If I hadn’t listened to the real game I tried not to know the score when I listened to the re-creation. If the Dodgers had lost, and I knew it, I didn’t listen. The knowledge was painful enough without having it dramatized.

Other things were taking place in the world. I knew that there was a civil war in China, something with the Communists. I knew there was something going on in Greece. I knew Truman was president and George Marshall was secretary of state. I now knew the facts of life. I knew that it was thought dangerous to swim in the summer because you might get infantile paralysis. I knew a lot. But I didn’t care. What I cared about was sex and the Brooklyn Dodgers.

There was no other white person in sight when Robinson and Burke got out of the cab in St. Louis. The Royal Crest Hotel was a narrow three-story building with dingy red asphalt shingle siding and dirty windows. There was no doorman. The door was narrow and had a dirty glass panel. It opened into a pinched lobby, lit by a hanging bulb, with just room for a small reception desk behind a wire mesh partition. The place smelled bad. The desk man was a thick-bodied Negro with yellowish skin and a fat neck. He looked at them without speaking.

“I called earlier,” Burke said. “About a room, for me and Mr. Robinson.”

The desk man’s eyes shifted.

“Didn’t tell me you was white,” the desk man said.

“Forgot,” Burke said. “We need a double room.”

“Colored only,” the desk man said.

“I’m with him,” Burke said. “Pretend I’m a mulatto.”

The desk man stared past them at the front door.

“Colored only,” he said.

Robinson took a five-dollar bill from his pocket and laid it on the counter in front of the little opening in the wire mesh.

“We need the room,” he said.

The desk man stared at it.

“Ain’t even sure that it ain’t against the law to domicile colored and white together,” he said.

A set of narrow stairs wound behind the reception desk. A colored man and woman came down the steps and saw Burke and stopped abruptly and stared at him. Then they quickly looked away, skirted him as widely as the small space permitted, and slipped out the front door.

Burke took the .45 from under his coat and aimed it carefully at the desk man’s nose.

“What’s the law on me shooting you in the fucking nose?” Burke said.

The desk man shrank back a little before he froze still. Robinson put his hand on Burke’s arm and pushed the gun down.

“Step outside a minute,” he said. “Let me talk to this man.”

Burke put the gun away and went and stood outside the front door and looked at the street. It was hot, the way Guadalcanal had been, steaming and dense. The buildings came right to the sidewalk. Around their foundations weeds grew. Where there was paint it was faded and peeling. Four or five small black children in shabby clothes stood across the street from the hotel and stared at Burke. A window went up in the paintless gray building behind them and a woman’s voice shouted something Burke couldn’t hear. The kids turned and straggled away down the littered alley between the houses. A blue 1939 Plymouth sedan went by. It slowed as it drove past Burke. Dark faces stared out of its windows at him. An empty pint bottle was tossed out the window. The bottle broke and the car picked up speed and drove away. The door behind Burke opened.

“Desk clerk decided to let us in,” Robinson said.

They went in. The desk clerk wouldn’t look at Burke. They walked up the stairs behind the desk, two flights, to a room that looked out at the sagging porch on the back of a tenement. The stairs smelled as if someone had vomited. When Robinson opened the door, the heat came out like a physical thing. Robinson walked to the one window and pushed up. The window was stuck. He put a hand on each corner and spread his legs and bent his knees and heaved. The window didn’t budge. He looked at Burke.

“Take one side,” he said.

Burke stood on the left side and Robinson on the right.

“On three,” Robinson said.

He counted. At three they heaved, and the window went up. They looked at each other for a moment, and Robinson nodded very slightly. Each of them almost smiled. The air outside wasn’t much better.

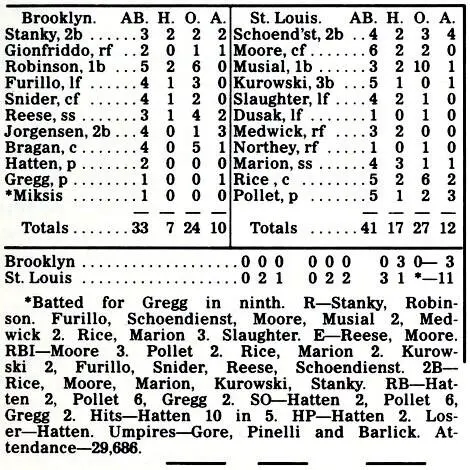

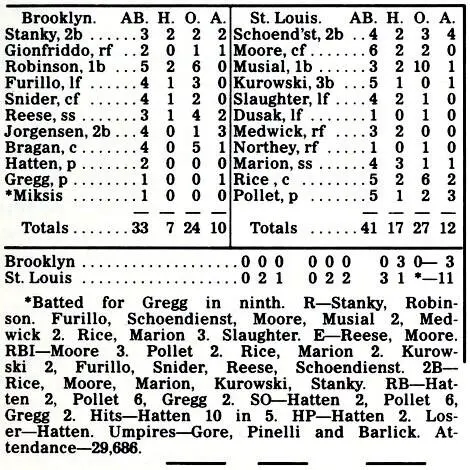

Box Score 3

After a night game at Crosley Field it took them a long time to find a cab. The white cabbies wouldn’t pick up a Negro, and the black cabbies were afraid to pick up a white man. Finally Burke went and stood in the doorway and Robinson flagged a cab driven by an aging gray-haired black man. Robinson got in.

“Looking for a place to eat, open late,” Robinson said.

“Sho’,” the cabbie said. “Take you over to Gaiter’s. Nice southern cookin’.”

“Good,” Robinson said.

He gestured at Burke.

“Wait till my friend gets in,” Robinson said as Burke stepped out of the doorway and walked across the sidewalk.

“Jesus Christ,” the cabbie said.

“It’s okay,” Robinson said. “You know who I am.”

“I do,” the cabbie said. “But I can’t take no white man.”

“He can slouch way down,” Robinson said.

“I get lynched carrying some ofay,” the cabbie said. “You want me gettin’ lynched.”

Burke got into the car and sat beside Robinson in the back seat.

“We can’t eat together anywhere that’s open now, less we go to the right part of town,” Robinson said. “We need to eat.”

Burke took out a twenty-dollar bill, folded it in half the long way, and held it toward the cabbie. The cabbie eyed it. He ran the tip of his tongue over his lower lip. Then he took the bill, folded it again and tucked it into his shirt pocket.

“White gennelman has to sit way down and back,” the cabbie said to Robinson.

He didn’t look at Burke.

Robinson said, “Thank you,” and the cab pulled away from the curb. The cabbie drove with both hands on the wheel, careful at cross streets, slowing at intersections. He let them off on a near empty street in front of a glass-fronted restaurant with a large Schlitz beer sign glowing in the window. The door was canopied in purple canvas and on the canvas in gold letters was GAITER’S FINE DINING.

Читать дальше