He talked pretty good, Burke thought, for a guy who hit .239 lifetime.

In April 1947 I was still fourteen. I would be fifteen in the fall. That month Columbia Records brought out Claude Thornhill’s “Snowfall.” RKO released The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer, with Cary Grant and Shirley Temple. In South Africa, Zulus danced for the British royal family. In China, Communist insurgents withdrew from Yenan in the face of Nationalist advances. Deborah Kerr bought a house in Los Angeles. The Jewish underground burned a Shell oil dump in Haifa. And when the Dodgers played the Braves on Opening Day, Jackie Robinson played first base for Brooklyn.

April 15 was a Tuesday, and my mother let me stay home from school to listen. It was as if I saw the event. Burnished black face. Bright white uniform. Green grass. I remember Red Barber’s familiar southern voice saying, I believe, “Robinson is very definitely brunette.” I remember thinking how marvelously delicate that was. The event couldn’t be ignored. But it needed to be reported neutrally. Barber had his own signature way of speaking. A big rally meant that a team was “tearing up the pea patch.” An outfielder running down a long fly ball was “on his mule.”

An argument was a “rhubarb.” If the Dodgers had three men on, the bases were “F.O.B.” — full of Brooklyns. If a particularly good hitter was coming up in a particularly crucial spot, Barber would give it a proper introduction as in — “Two on, two out, and here comes Musial.” When he was excited, Barber would say, “Oh, doctor!” Such language seemed, at the time, the way one was supposed to describe a baseball game. Any other way would be inadequate.

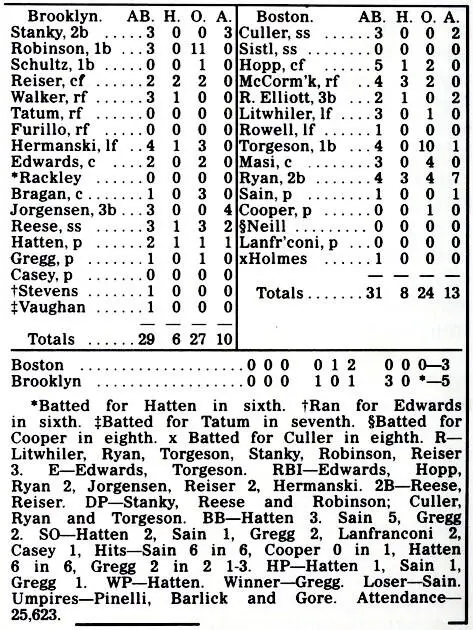

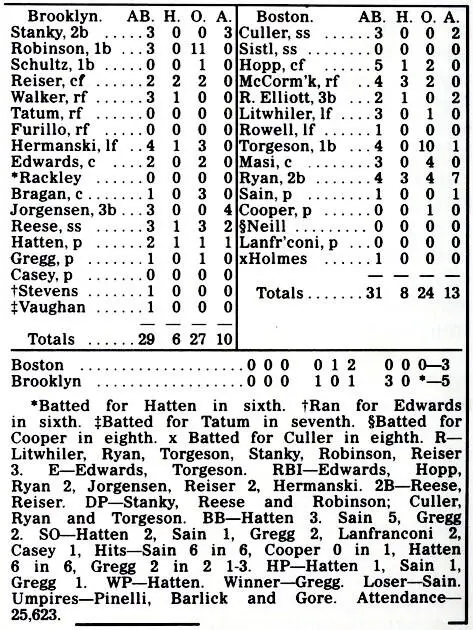

In the newspapers, I read every box score. Not just the Dodgers, but every team. I felt that I ought to keep track of what was going on all over baseball. In Cincinnati, in Washington. I subscribed to The Sporting News and often read the box scores from the high minors. I could name the starting lineup for Montreal, in the International League, and St. Paul in the American Association. You can learn a lot from a box score.

Box Score 1

It didn’t take Burke long to pick up the way it was going to be. Pee Wee Reese was supportive. Dixie Walker was not. Everyone else was on the spectrum somewhere between.

In St. Louis the base runner spiked Robinson at first base.

In Chicago he was tagged in the face sliding into second.

In Philly somebody tossed a black cat onto the field.

In Cincinnati he was knocked down three times in one at bat.

In every city he heard the word nigger out of the opposition’s dugout.

There was nothing Burke could do about it. He sat near the corner of the dugout and did nothing. His work was off the field.

There was hate mail. Death threats were forwarded to the police, but there were too many of them. All Robinson and Burke could do was be ready. After a doubleheader against the Giants, Burke drove Robinson uptown. A gray two-door Ford pulled up beside them at a stoplight and Burke stared at the driver. The light changed and the Ford pulled away.

“I’m starting to look at everybody as if they were dangerous,” Burke said.

Robinson glanced over and smiled. The smile said, Pal, you have no idea.

But all he said was, “Un huh.”

They stopped to eat at a restaurant on 125th Street. When Burke and Robinson entered, everyone stared. At first Burke thought it was Robinson. Then he realized that they were staring at him. He was the only white face in the room.

“Sit in the back,” Burke said to Robinson.

“Have to, with you along,” he said.

As they walked through, the diners recognized Robinson and somebody began to clap. Then everybody clapped. Then they stood and clapped and hooted and whistled.

“Probably wasn’t for me,” Burke said.

“Probably not.”

Robinson had a Coke.

“You ever drink booze?” Burke said.

“Not in public,” Robinson said.

“Good.”

Burke looked around. It surprised him that he was uncomfortable being in a room full of colored people. He would have been more uncomfortable without Robinson.

They ordered steak.

“No fried chicken?” Burke said.

“Not in public,” Robinson said.

The room grew suddenly quiet. The silence was so sharp that it made Burke hunch forward so he could reach the gun on his hip. Through the front door came six white men in suits and overcoats and felt hats. There was nothing uneasy about them as they came into the colored place. They swaggered. One of them swaggered like the boss, a little fat guy with his overcoat open over a dark suit. He had on a blue silk tie with a pink flamingo hand painted on it.

“Mr. Paglia,” Robinson said. “He owns the place.”

Without taking off their hats or overcoats, the six men sat at a large round table near the front.

“When Bumpy Johnson was around,” Burke said, “the Italians stayed downtown.”

“Good for colored people to own the businesses they run,” Robinson said.

A big man sitting next to Paglia stood and walked over to the table. He was big. Bigger than either Robinson or Burke. He was thick-bodied and tall, with very little neck and a lot of chin. His face was clean-shaved and had a moist glisten. His shirt was crisp white. His chesterfield overcoat hung open, and he reeked of strong cologne.

“Mr. Paglia wants to buy you a bottle of champagne,” he said to Robinson.

Robinson put a bite of steak in his mouth and chewed it carefully and swallowed and said, “Tell Mr. Paglia, no thank you.”

The big man stared at him for a moment.

“Most people don’t say no to Mr. Paglia, Rastus.”

Robinson said nothing, but his gaze on the big man was heavy.

“Maybe we can buy Mr. Paglia a bottle,” Burke said.

“Mr. Paglia don’t need nobody buying him a bottle.”

“Well, I guess it’s a draw,” Burke said. “Thanks for stopping by.”

The big guy looked at Burke for a long moment, then swaggered back to his boss. He leaned over and spoke to Paglia, his left hand resting on the back of Paglia’s chair. Then he nodded and turned and swaggered back.

“On your feet, boy,” he said to Robinson.

“I’m eating my dinner,” Robinson said.

The big man took hold of Robinson’s arm, and Robinson came out of the chair as if he’d been ejected and hit the big guy with a good right hand. Robinson was nearly two hundred pounds, in good condition, and he knew how to punch. It should have put the big man down. But it didn’t. He took a couple of backward steps and steadied himself and shook his head as if there were flies. At Paglia’s table everyone turned to look. The only sound in the room was the faint clatter of dishes from the kitchen. Burke stood.

“Not up here,” Robinson said. “I’ll take it downtown, but not up here.”

The big man had his head cleared. He looked at the table where Paglia sat.

“Go ahead, Allie,” Paglia said. “Show the nigger something.”

The big man lunged toward Robinson. Burke stepped between them. The big man would have run over him if Burke hadn’t hit him with a pair of brass knuckles. It stopped him but it didn’t put him down. To do that Burke had to get a knee into his groin and hit him again with the brass knuckles. The big man grunted and went down slowly, first to his knees, then slowly toppling face forward onto the floor.

There was no sound in the room. Even the kitchen noise had stopped. Burke could hear someone’s breath rasping in and out. He’d heard it before. It was his.

Читать дальше