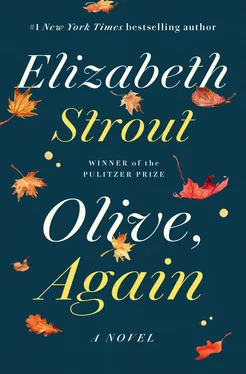

Olive, Again by Elizabeth Strout

For Zarina,

again

In the early afternoon on a Saturday in June, Jack Kennison put on his sunglasses, got into his sports car with the top down, strapped the seatbelt over his shoulder and across his large stomach, and drove to Portland—almost an hour away—to buy a gallon of whiskey rather than bump into Olive Kitteridge at the grocery store here in Crosby, Maine. Or even that other woman he had seen twice in the store as he stood holding his whiskey while she talked about the weather. The weather. That woman—he could not remember her name—was a widow as well.

As he drove, an almost-calmness came to him, and once in Portland he parked and walked down by the water. Summer had opened itself, and while it was still chilly in mid-June, the sky was blue and the gulls were flying above the docks. There were people on the sidewalks, many were young people with kids or strollers, and they all seemed to be talking to one another. This fact impressed him. How easily they took this for granted, to be with one another, to be talking! No one seemed to even glance at him, and he realized what he had known before, only now it came to him differently: He was just an old man with a sloppy belly and not anyone worth noticing. Almost, this was freeing. There had been many years of his life when he was a tall, good-looking man, no gut, strolling about the campus at Harvard, and people did look at him then, for all those years, he would see students glance at him with deference, and also women, they looked at him. At department meetings he had been intimidating; this was told to him by colleagues, and he understood it to be true, for he had meant to be that way. Now he sauntered down one of the wharfs where condos were built, and he thought perhaps he should move here, water everywhere around him, and people too. He took from his pocket his cellphone, glanced at it, and returned it to his pocket. It was his daughter he wished to speak to.

A couple emerged from the door of one apartment; they were his age, the man also had a stomach, though not as big as Jack’s, and the woman looked worried, but the way they were together made him think they had been married for years. “It’s over now,” he heard the woman say, and the man said something, and the woman said, “No, it’s over.” They walked past him (not noticing him) and when he turned to glance at them a moment later, he was surprised—vaguely—to see that the woman had put her arm through the man’s, as they walked down the wharf toward the small city.

Jack stood at the end of the wharf and watched the ocean; he looked one way, then the other. Small whitecaps rolled up from a breeze that he felt only now. This is where the ferry came in from Nova Scotia, he and Betsy had taken it one day. They had stayed in Nova Scotia three nights. He tried to think if Betsy had put her arm through his; she may have. So now his mind carried an image of them walking off the ferry, his wife’s arm through his—

He turned to go.

“Knucklehead.” He said the word out loud and saw a young boy on the wharf close by turn to look at him, startled. This meant he was an old man who was talking to himself on a wharf in Portland, Maine, and he could not—Jack Kennison, with his two PhDs—he could not figure out how this had happened. “Wow.” He said that out loud as well, past the young boy by now. There were benches, and he sat down on an empty one. He took out his phone and called his daughter; it would not yet be noontime in San Francisco, where she lived. He was surprised when she answered.

“Dad?” she said. “Are you okay?”

He looked skyward. “Oh, Cassie,” he said, “I just wondered how you were doing.”

“I’m okay, Dad.”

“Okay, then. Good. That’s good to hear.”

There was silence for a moment, then she said, “Where are you?”

“Oh. I’m on the dock in Portland.”

“Why?” she asked.

“I just thought I’d come to Portland. You know, get out of the house.” Jack squinted out toward the water.

Another silence. Then she said, “Okay.”

“Listen, Cassie,” Jack said, “I just wanted to say I know I’m a shit. I know that. Just so you know. I know that I’m a shit.”

“Daddy,” she said. “Daddy, come on. What am I supposed to say?”

“Nothing,” he answered agreeably. “Nothing to say to that. But I just wanted you to know I know.”

There was another silence, longer this time, and he felt fear.

She said, “Is this because of how you’ve treated me, or because of your affair for all those years with Elaine Croft?”

He looked down at the planks of the wharf, saw his black old-man sneakers on the roughened boards. “Both,” he said. “Or you can take your pick.”

“Oh, Daddy,” she said. “Oh, Daddy, I don’t know what to do. What am I supposed to do for you?”

He shook his head. “Nothing, kid. You’re not supposed to do anything for me. I just wanted to hear your voice.”

“Dad, we were on our way out.”

“Yeah? Where’re you going?”

“The farmers market. It’s Saturday and we go to the farmers market on Saturdays.”

“Okay,” Jack said. “You get going. Don’t worry. I’ll talk to you again. Bye-bye now.”

He thought he could hear her sigh. “All right,” she said. “Goodbye.”

And that was that! That was that.

Jack sat on the bench a long time. People walked by, or perhaps no people walked by for a while, but he kept thinking of his wife, Betsy, and he wanted to howl. He understood only this: that he deserved all of it. He deserved the fact that right now he wore a pad in his underwear because of prostate surgery, he deserved it; he deserved his daughter not wanting to speak to him because for years he had not wanted to speak to her—she was gay; she was a gay woman, and this still made a small wave of uneasiness move through him. Betsy, though, did not deserve to be dead. He deserved to be dead, but Betsy did not deserve that status. And yet he felt a sudden fury at his wife—“Oh, Jesus Christ Almighty,” he muttered.

When his wife was dying, she was the one who was furious. She said, “I hate you.” And he said, “I don’t blame you.” She said, “Oh, stop it.” But he had meant it—how could he blame her? He could not blame her. And the last thing she said to him was: “I hate you because I’m going to die and you’re going to live.”

As he glanced up at a seagull, he thought, But I’m not living, Betsy. What a terrible joke it has been.

The bar at the Regency Hotel was in the basement, the walls were dark green and the windows looked out at the sidewalks, but the sidewalks were high up in the windows, and mostly he could just see legs going by. He sat at the bar and ordered one whiskey neat. The bartender was a pleasant fellow. “Good,” Jack said when the young man asked how he was today.

“Okay, then,” said the bartender; his eyes were small and dark beneath his longish dark hair. As he poured the drink, Jack noticed that he was older than he had first seemed, although Jack had a hard time these days figuring out the age of people, the young especially. And then Jack thought: What if I’d had a son? He had thought this so many times in his life it surprised him that he kept wondering. And what if he had not married Betsy on the rebound, as he had? He had been on the rebound, and she had been as well, from that fellow Tom Groger she’d loved so much in college. What then? Troubled but feeling better—he was in the presence of someone, the bartender—Jack laid these thoughts out before him like a large piece of cloth. He understood that he was a seventy-four-year-old man who looks back at life and marvels that it unfolded as it did, who feels unbearable regret for all the mistakes made.

Читать дальше