The next day, Sunday, after lunch, Cindy returned to bed, and Tom came upstairs with her, trying to be helpful, arranging the pillows, straightening the quilt.

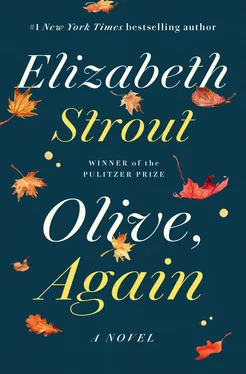

A car could be heard coming up the driveway, and Tom pulled back the curtain and looked out. “Oh Christ,” he said. “It’s that old bag. Olive Kitteridge. What in hell is she doing here?”

“Let her in,” Cindy said, her voice muffled in the pillows.

“What, sweetheart?”

Cindy sat up. “I said, let her in. Please, Tom.”

“Are you crazy?” Tom asked.

“Yes. Let her come in.”

And so Tom went down the stairs and Cindy heard him open the front door, which they never used, and in a moment Mrs. Kitteridge came up the stairway, followed by Tom, and she stood in the doorway of the bedroom. She wore her red coat, which was rather puffy, the way winter coats can be.

“Hi, Mrs. Kitteridge,” Cindy said. She sat up in the bed, putting the pillows behind her back. “Tom, can you take her coat?” And so Mrs. Kitteridge took off her coat and handed it to Tom, who said, “Cindy? You want me to stay?” Cindy shook her head at him, and he went back downstairs with the coat of Mrs. Kitteridge.

Mrs. Kitteridge was wearing black slacks and a jacket-type thing that went halfway down her thighs; its print was of bright reds and orange swirls. She placed her black leather bag on the floor. “Call me Olive. If you can. I know sometimes a person can’t when I’ve been Mrs. Kitteridge all their life.”

Cindy looked up at this woman before her; she saw in her eyes a distinct light. “I can call you Olive. Hello, Olive.” Cindy looked around and said, “Here, pull up that chair.”

Olive pulled the chair over toward the bed, it was a straight-back chair, and Cindy hoped that she could fit on it comfortably. But with her coat off, Olive didn’t look quite as large, and she sat on the chair and folded her hands in her lap. “I thought if I called you might say I shouldn’t come over.” Olive waited. Then she said, “And I thought, hell’s bells, I want to go over and see that girl. So I just got in the car and came.”

“It’s fine,” Cindy said. “I’m glad you did. How are you, Olive?”

“The question is you. You’re not okay.”

“No, I’m not.”

“Any chance you will be?”

“Fifty percent. Is what they say.” Then Cindy added, “I have my last treatment next week.”

Mrs. Kitteridge looked straight at Cindy. “I see,” she said. Then she looked around the room—at the white bureau, and the clothes hanging over another chair in the corner, and all the books stacked on the windowsill—before looking back at Cindy. “So you feel crappy? What do you do all day? Do you read?”

“It’s a problem,” Cindy acknowledged. “Because I do feel crappy. And I don’t read as much as I used to. I can’t really concentrate.”

Olive nodded, as though considering this. “Yuh,” she said. Then she added, “Hell of a mess to be in.”

“Well, it is kind of.”

“I should say so.” The woman sat there, her hands still folded in her lap. It didn’t appear she had anything else to say.

And so Cindy blurted out, “Oh, Mrs. Kitteridge. Olive. Oh, Olive, I’m so— I’m so angry .”

Olive nodded. “I should think to God you would be.”

“I want to feel peaceful, I want to accept this, but I am so angry, I’m just angry every minute, and when I saw you in the store, people had been looking at me. I don’t want to go out, people look at me and they get afraid.”

“Yuh,” Olive said. Then she added, “Well, I’m not afraid.”

“I know that. I mean, I appreciate it.”

“How’s Tom?”

“Oh, Tom .” Cindy sat up, and the bedclothes seemed to her almost soiled, although they had been changed the day before, but there was that faint odor of something like metal that she had smelled for months now. “Olive, he keeps talking like I’ll get better. I can’t believe it, I just can’t believe it, it makes me so lonely, oh dear God, I am so lonely.”

Olive made a grimace of sympathy. “God, Cindy. That sucks. As the kids used to say. That really sucks.”

“It does.” Cindy lay back on her pillow, watching this woman who had come over uninvited. “There’s a nurse who comes in twice a week, and she told me Tom was acting like every man she’s ever seen in these situations. That men just can’t deal with it. But it’s terrible, Olive. He’s my husband and we’ve loved each other now for many years, and this is awful.”

Olive sat looking at Cindy, then looking at the foot of the bed. “I don’t know,” she said. “I don’t know if it’s a male thing or not. The truth is, Cindy, I wasn’t very good to my husband during his last years.”

Cindy said, “Yes, you were. Everyone knew—you went to the nursing home every day to see him.”

Olive shook her head. “Before that.”

“He was sick before that?”

“I don’t know,” Olive said thoughtfully. “He may have been and I just didn’t know it. He became very needy. And I wasn’t— I just wasn’t very nice to him. It’s something I think about a lot these days, and it bugs me like hell.”

Cindy waited a moment. “Well, if you didn’t know he was sick—”

Olive heaved a deep sigh. “I know, I know. But I’m just saying, I wasn’t especially good to him, and it hurts me now. It really does. At times these days—rarely, very rarely, but at times—I feel like I’ve become, oh, just a tiny—tiny—bit better as a person, and it makes me sick that Henry didn’t get any of that from me.” Olive shook her head. “Here I go, talking about myself again. I’ve been trying not to talk about myself so much these days.”

Cindy said, “Talk about anything you want. I don’t care.”

“Take a turn,” Olive said, raising a hand briefly. “I’m sure I’ll get back to myself.”

Cindy said, “One time, it was on Christmas Day, I just began to cry. I cried and cried, and my sons were both here and so was Tom, and I stood on the stairs, just wailing, and then I noticed that they had all left, they walked away from me until I stopped crying.”

Olive’s eyes closed briefly. “Oh Godfrey,” she murmured.

“I scared them.”

“Yuh.”

“And now they will always think of that, every Christmas to come, my sons will remember that.”

“Probably.”

“I did that to them.”

Olive sat forward and said, “Cindy Coombs, there’s not one goddamn person in this world who doesn’t have a bad memory or two to take with them through life.” She sat back and crossed her feet at her ankles.

“But I’m scared!”

“Oh, I know, I know, of course you are. Everyone is scared to die.”

“Everyone? Is that true, Mrs. Kitteridge? Are you scared to die?”

“I am scared to death to die, is the truth.” Olive adjusted herself on the chair.

Cindy thought about this. “I’ve heard of people who make peace with it,” she said.

“I guess that can happen. I don’t know how they do it, but I think it can happen.”

They were quiet. Cindy felt—she almost felt normal. “Well,” she said finally. “It’s just that I’m so alone. I don’t want to be so alone.”

“ ’Course you don’t.”

“You’re scared to die, even at your age?”

Olive nodded. “Oh Godfrey, there were days I’d have liked to have been dead. But I’m still scared of dying.” Then Olive said, “You know, Cindy, if you should be dying, if you do die, the truth is—we’re all just a few steps behind you. Twenty minutes behind you, and that’s the truth.”

Читать дальше