“Do we have anything to eat?” Louie asks Perrine.

She rummages in the bag, hands each of them an egg.

“Yuck,” says Noah. “Eggs again.”

The hens look at them with their round eyes, heads tilted, waiting for the shells. Perrine pours them some water in a saucer and strokes the head of one of them.

“You see, they’re tame, now.”

They gaze fascinated at the sunrise, minute upon minute, second upon second even, as the sphere of light appears from below the horizon. The dazzle of sunlight on the water forces them to close their eyes from time to time, they shield them with their hands, and eventually turn away.

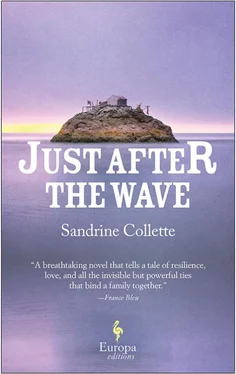

On the other side is the island. They can see it better now. An island with greenery: trees, and thickets. Their stomachs rumble at the thought they might find fruit; they wish they could be there already. They stare avidly at the hut, but there’s still no sign of movement anywhere around it. And yet yesterday, they thought there had been.

Illusion.

“Come on,” says Louie, “let’s try and catch some fish first.”

So again they cast their tiny lines, little nylon threads which the sea encloses and strokes, their colorless lures floating and bobbing on the surface. But Noah was wrong: once again the lines remain slack. Sometimes a line dips down and they sit up and pull it towards them—only mirages, every time, the hook is empty and the potato bait remains intact.

“Who cares about the fish,” Noah complains after a while.

But Louie is intractable.

“We have to keep trying.”

“Never mind,” says Perrine. “If we can go cook the potatoes we didn’t have time to do before we left, that would already be a good thing.”

“Let’s wait for a while.”

“I’m sick of this,” Noah sighs, bringing his fishing pole back on board.

“With you it’s just the same as with mushrooms, if there aren’t loads of them right away, you get annoyed.

“Yeah, but I don’t like mushrooms, anyway.”

The boy leans over the edge, toward the anchor chain. Shall I pull it up?

“Go ahead,” says Louie, exasperated, “we’ll keep going for a while.”

They hear the familiar creaking, Noah’s breathing imitating Pata’s and Louie’s, Heave , he says, and Perrine helps him with the anchor, at that very moment out of the corner of his eye Louie sees something moving by her fishing pole. He shouts and points to it.

“Perrine, your line!”

He stands up suddenly when he sees the line go taut. His initial reflex, before the others have even realized, is to climb over the seat to grab the pole that is about to flip up and over; but then, once his hands have closed around the wood, he freezes. It’s not the weight of the creature on the other end of the hook that worries him, no, even if the line is stretched fit to snap. It’s something else, something weird.

He can’t explain what it could be.

But it’s pulling too hard and the pole has bent down to touch the water.

He cries out.

“That’s no fish on the hook!”

“What?” Noah says, alarmed.

Louie hands the pole to Perrine and hurries toward the oars.

“It’s shaking too much! It’s not a fish!”

“But what is it?”

The older boy doesn’t answer. He plunges the oars in the water to move the boat away quickly, he doesn’t know why, it’s just a danger he can sense around them, underneath them, he screams at Perrine:

“Let go of your pole! Let it go!”

The little girl, leaning over the water to try and hold her pole straight, stands up now, astonished. Really? At the same time, emerging from the sea with a gigantic thrust, with a burst of spray clear across the boat, comes an arm, fingers curved, an arm then an upper body, a head with its mouth open as if to roar, streaming, enormous, targeting Perrine for sure, until it falls back in the water a few inches from the terrified little girl.

They scream, all three of them.

“What is it?”

“Get back, get back!” shouts Louie, pulling on the oars as hard as he can.

“A monster, a monster!” Noah shrieks.

No, it’s a man.

“Come help me!” Louie shouts again.

Who is after them.

“Come on!”

God, the man is swimming faster than the boat can move.

“But where’d he come from?” says Perrine in a panic.

Louie doesn’t answer, terrified. So the island wasn’t empty. There’s no other explanation—around them, the sea is as smooth as the day before; only the rippling and terrifying spray in their wake, the sound of those huge breaststrokes, brown skin beneath the water. He screams again, Help me!

Perrine grabs the second oar. Louie hands his to Noah, bellows, Row, row! and hunts under the seat for the emergency oar. There’s one on every boat. There has to be.

Not there.

The other seat? With trembling hands and a pounding heart.

He feels it under his fingers at the very moment when the swimmer hoists himself up to their height, grabbing the gunwale with such strength that the small craft heels violently; all three of them are thrown off balance, and the man too, who surely wanted to lean on the gunwale, a fraction of a second, just time enough for Louie to raise the oar and bring it down on him, the way he did with Ades, the image is there before him, with all his strength, smack on the head, yes, exactly the same, except for the piercing scream from Louie’s throat, Noooo! he doesn’t know why he shouted this time, fear, prayer, rage.

And this time too the man tips into the sea. For an instant Louie vibrates with the victorious fear in his guts, the man will wave his arms with cries of rage and terror, he’ll sink, that’s it, just like Ades, exactly.

No, he won’t.

The difference is that when he flipped backwards, either instinctively or with an insane force of will, the swimmer grabbed the oar.

Louie feels it, that he doesn’t have time to let go.

The thought goes through him: he’s caught already.

Off balance, he falls in the water. All he hears is Perrine’s scream and the sound of the water opening to him.

He falls, almost into the arms of the stunned man, who is holding out a hand, an instinctive, animal reaction—grab hold of the kid not to drown. Louie spits out the water from his throat and nose, sees the blood on the man’s face, wants to call out, pulls away from the fingertips touching him as they cling to his T-shirt, a cry at last, to Perrine and Noah, petrified on the boat, Row! Row! And then the words stop, no more room, all he can see is the fingers like claws groping for him, moving through the sea, he slaps his hands, kicks his feet, the man is after him, grazing him every time, Louie dodges, panicking. His gestures are becoming disjointed, from fear, from a lack of breath, from those arms too near, obsessing him, they’re all he can see, those arms and the spray of the sea where they’re struggling, the man will catch him, he will, Louie has no more strength. So he thinks of Pata who used to send him after the wild ducks when they went hunting, Pata who didn’t want to get another dog when his spaniel died, he said it hurts too much when they leave you, so it was Louie who ran through the swamps and swam out to get the birds, it was a game they played, Pata shooting his rifle and Louie swimming out. Yes, Pata said Louie was the best dog he’d ever had, the fastest to sprint over there and slip into the water, lively and nervous, he always found the ducks, the best, the best.

Swim!

He dives underwater, deeper down, getting away from the man and his shouts as he tries to stay on the surface. He filled his lungs just before, now he has slipped into the sea, his arms close to his sides to be as smooth as a fish, his feet kicking the ocean, three seconds, five seconds, ten. No time, no courage to look behind him, until he surfaces with a hoarse intake of breath, Perrine and Noah are on their feet in the boat, and cry out when they see him.

Читать дальше