A thief?

Perrine said: There’s no one here. But just in case. Louie heard him, and he snickered.

“With your shitty stick, sure. He’ll have a knife. Or even a rifle.”

Noah trembles.

Still not from cold; he wipes the sweat from his brow.

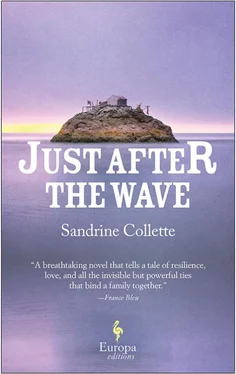

Could Pata be on his way back already? He spreads his fingers one by one to count, gets a little mixed up. Five days? Six? In any case, he can’t keep watch on the sea, with his head constantly swinging left to right because of the sounds. What could still be on the island? What creatures, what monsters? Noah sits down, his heart pounding.

He looks at the house. He looks at the sea.

House. Sea.

Which way lies the greatest fear?

In the early morning, on leaving his bedroom Louie almost trips over the little boy. Noah is sleeping across the threshold, curled up in a ball, his head on a blanket. He is snoring gently—or has a draft given him a cold? Louie prods him with his toe the way you turn over a dead fish on the shore.

Then leaves him.

What’s the point.

Noah lingers behind. From where he is, he knows he can run away if Louie tries to catch him. Run away, how far would he get, on this island which the sea is nibbling at a little bit more every day—but it comforts him to know that he can run a few dozen yards away. He watches for the older boy’s reactions, he and Perrine are by the shore, bending over, looking at something. He thinks: I don’t want to go there ever again, not ever, ever .

Deep inside he feels a certain pride, in spite of his fear that Louie will beat him. It took him a while, last night, with his scrawny arms and little legs, to drag all those cinder blocks into the ocean.

Destroy the tower: yes. So that he wouldn’t be sent there anymore. A once and forever solution. If he’d just taken it apart, the others would have told him to build it again. But this way. He threw the rubble in from the promontory, where the boat used to be moored. Where the water is six or eight feet deep.

He left the door there: too heavy. And besides, what would they do with the door all on its own?

So Noah is watching his siblings, who are looking in the water to see if they can fish out the cinder blocks. He is humming to himself, his voice inaudible, You can’t, you can’t. He feels all the tension in his body, because he knows he’s done something wrong. To break the silence he shouts, legs spread, ready to hightail it:

“And anyway, it was no use!”

No reply. Louie and Perrine are sitting facing out to sea, their backs to him. After a moment, Noah goes over to them, impatient— What are you doing?

“Go away,” says Louie.

“But what are you doing?”

“None of your business.”

“Come on.”

“Scram.”

The older boy starts to get up, and Noah backs away, goes to sit a bit further away. He hopes he’ll be able to hear what they are saying, but the wind prevents him.

“Are you going to go and get some more potatoes?”

“There’s no more raft, you idiot!”

“I’m hungry!”

That morning, Perrine made a batter with fresh eggs, and cooked up twenty or thirty pancakes on the still-warm stove so they’d have a supply. Louie made a list of what they had left to eat, and it didn’t match the list Madie had left them, there is much less than they expected, even though Perrine had divided it all up into little piles; he doesn’t get it. His sister confesses: she had to take from a pile here and there because they didn’t have enough.

How will they manage now, for the last days?

With tears in her eyes Perrine says she doesn’t know. They were hungry, that was all.

“Let’s do the piles again,” murmurs Louie. “But no changing them this time, you hear?”

In the house, once again they make piles of cans, potatoes, eggs. Behind them Noah empties the cupboards to hand them the food, copying them, mute and conciliatory. So he is startled when Louie grabs a can of raviolis from him and growls:

“You’re pleased with yourself, because of the tower, aren’t you, blockhead.”

Noah cringes, makes himself small, maybe hoping for pity, for sure to become invisible. He looks down, hands him another can.

“Blockhead,” says Louie again.

In the end, they have enough food for six days.

“It’s not a lot,” says Perrine.

Noah points to the cans: I don’t like green beans or broccoli.

“We’ll eat eggs,” says Louie. “The hens lay every day. And with milk and flour we can make pancakes.”

“Every day?”

“Every day.”

Noah’s eyes are shining.

* * *

Sitting close to the house to avoid the first drops of rain, they are eating pancakes with jam. Perrine fills their glasses with orange juice; they have enough bottles of water and soda to last for weeks. Liam and Matteo brought back entire packs from the neighbors’. Farther away, the sea still shifts its cargo of bits of wood, floating objects, plastic. Maybe there are still bodies, too, but they’ve stopped looking, they’ve become accustomed, to be honest, in the beginning it was exciting, the thought that those were dead bodies going by, but now. They’re afraid it might be Madie or Pata, or their big brothers, or their little sisters. What if they capsized, and the sea brought them all the way back to the place they were hoping to get away from? And it’s not so much the burden of sorrow that would be hard to bear, but knowing that now no one will be coming to get them.

“It’s getting higher, isn’t it?”

Perrine didn’t move her head when she asked. She doesn’t need to say what she’s referring to, and Louie gazes at the gray sea, waves just starting to toss with bad weather.

“Yes, I think so.”

No, he doesn’t think so: he knows so. Every morning, the way Pata did before him, he checks the water level on the stairs to the basement. When the parents left, he had marked the third step; now the sea is attacking the sixth one. That means they need boots to go to the ground floor. The previous day they saw that the sea was gradually eating its way across the living room floor and into the kitchen, so they sweated blood to drag the old stove up the stairs. Too exhausted to drag it any further, they left it in the corridor by the stairs. At the bottom of the garden, they will soon be sitting on the pontoon with their bottom in the water. Every evening for the last four days, Louie has been planting a stake precisely where, on the terrain, the water has reached. Every morning, he measures the distance the sea has advanced during the night. Twelve, sixteen inches. One day there was nothing, and he hoped this meant the drop in the water level Pata had spoken about so often—but it was probably only because it had been a very sunny day, because the following day, the water was rising again.

What a strange climate the great tidal wave has imposed on them, with these constant storms, this inconstant, spinning sky. They have learned how to read the portents of storms—sudden choppy water, initially just splashing onto the shore, then proper waves washing onto the land. At the same time the wind rises, whistling and gyrating, intoxicating the sky, filling it with shadows. The veiled sun gives off a terrifying yellow light, that is what they remember above all, the world gone yellow right down to their own faces when they look at each other, anxiously, the sickly reflection of a world that has yet to finish dying. The surface of the water looks as if it has been ploughed full of holes, black eddies, and wherever they turn the sea seems to be gathering in upon itself, growling, towering in turbulent rollers that have formed out to sea, that charge through the spray and make the children recoil. In the house they yank the shutters closed and take refuge upstairs. Perrine throws floorcloths down against the doors to block the gaps, with Noah’s help, running crazily here and there.

Читать дальше