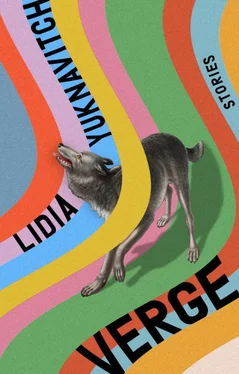

Лидия Юкнавич - Verge - Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Лидия Юкнавич - Verge - Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2020, ISBN: 2020, Издательство: Riverhead Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Verge: Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Riverhead Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2020

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-52553-487-7

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Verge: Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Verge: Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A fiercely empathetic group portrait of the marginalized and outcast in moments of crisis, from one of the most galvanizing voices in American fiction. cite

Verge: Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Verge: Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Nor is it possible to tell who is liberal or who is conservative or nuts or brilliant or a criminal or a good citizen. All the façades need new coats of paint, all the yards need care. Even our fences are leaning toward giving up. The spaces between houses hold their secrets: overflowing trash cans and piles of broken flowerpots, garden hoses all snarled up and molding, our efforts at beautiful landscaping creating their own ridiculous labyrinths between our homes. I’ve noticed that my neighbor Clark and I both wear sweatpants and sneakers after five and on weekends. Clark may be an alt-righter; he may be just a guy who lives in his mother’s basement. In our Nike uniforms, who can tell?

In our hearts we meant to complete all the projects, spiff up our neighborhood, improve our homes and selves. In reality we’re too fucking tired from too many jobs or kids or just the idea that nothing turned out the way we dreamed it would. Our sad little dream balloons, once swollen with hot air, deflating slowly like my aging breasts.

On the other hand, money isn’t what makes our houses homes.

For example, instead of filling my house with things that cost money, I’ve filled it with things that comfort me: Plates and bowls filled with rocks and feathers and the small bones of animals. Cups with azure beads. Seashells and talismans and trinkets. And books. More books than you can possibly imagine. Books in every room, shelved, on tables, in stacks on the floor.

Books saved me from my former self.

About the only thing of serious value to me inside my house is a vintage Royal typewriter we lugged all the way back from France, imagining that some famous expat writer might once have plunked out something brilliant on it. And a coffee table and a rug I bought when I got tenure—my first non-garage-sale “furniture.”

I teach literature in college now. I write. I’ve become… well, we don’t say “bourgeois” very much in America, although these days the students love to say “bougie.” I’ll just say middle-class.

But we all know there’s no such thing as middle-class.

IN MY NEIGHBORHOOD they have developed a yearning for the dreaded neighborhood watch. Guy down the street stops me one night as I’m headed home, lead-armed with groceries—he’s never spoken to me in his life; I’ve never even seen him poke his mole skull out of his white house—and he’s bobbing his head around like a scared rodent, his eyes darting out of their sockets, so titillated he’s sweating. Have you noticed the problem ? he says. What problem? You know. He looks one way, then the other. Go ahead, I’m thinking, no cars are coming, we’re on our own street, we’re in front of our own houses. He continues: All the dope peddling . The drug deals. And that woman being paraded up and down the street, all day all night every day every night. My God, we need to stand together before it’s too late. There is a long pause while we consider this. Whose god? I wonder. I feel myself turn on him. Is my neighbor a white supremacist? A fascist? A bigot? A MAGA voter? Then I’m just me again.

Who could miss it? What moron wouldn’t notice? Not because they’re doing anything to us but because they’re doing it too near us.

The needle against the flesh threatens us with its obscenity, its mechanism of invading living skin.

I carry my groceries back to my house. Clark, my sweatpants twin, the one across the street who lives with his mother and wears undersize rock concert T-shirts and the exact same baseball cap every day of his life, a guy who inherited his money from an accident on the job, a fact that now works him over into bitter and pale and beer-bellied and pot-eyed, waves to me from the other side of the street. Then he crosses and stands on my lawn and says, They’ll never change. It’s like I always say, once a junkie, always a junkie.

I feel anger welling up in my belly. For an instant I want to hurl my knowledge at him like obscenities. Instead of saying, Shut the hell up, you ignorant asshole, I want to scream, Keats! Byron! Shelley! Van Gogh! Bacon! Eliot! Faulkner! For some reason I feel a list of M’s rise up in my throat: Mozart , Mingus , Monk , Munch , Miller , Malcolm even! I want to move on to Germans, Africans, Latin Americans, Russians, French, Swiss, periods, genres. I want to say, If we didn’t have junkies, we wouldn’t have art, but I don’t. I just stare at him until he turns away and walks silently back to his yard, his front door, and gone. Anyway, it isn’t true. Addiction doesn’t make art. Does it? What the hell am I worked up about? It’s just Clark .

I turn back toward my own house. Then it hits me: We are alike in our silences.

INSIDE, MY HUSBAND is in his ad hoc studio, painting. Just a half room in our old falling-apart house, much like my writing room, carved out of the small space that would ordinarily be a kid’s room. We don’t make enough to rent him studio space, so we do what we all do: invent ways to live what we cannot have. I set the groceries down with relief—not because I’m tired but because I know he is responsible for dinner, because never again will I have to be responsible for dinner. This is part of my love for him. You’ll never know the relief that a junkie or a woman can feel when the pressure of the giant script of Woman or Wife begins to lift.

And he loves me, too, because I can kiss the jagged scars on his wrist like it bleeds a sweet white sugar. And he can butterfly-kiss the collapsed veins on my left arm under all the long-sleeved shirts I wear to work. We are still learning to live in these houses, these lives. We are loving over our outcast and beaten hearts. For the longest time, neither of us could afford therapy, insurance, or any other route to wellness. Today we probably could afford some kind of medical cure for maybe one of us, but neither of us has that much investment in attending to the hard-core addictions anymore, which is just as well. Easier to just keep drinking wine, downing prescription medications, moving potward down the road of our lives. The easy, low-key addictions of homeowners.

Cherise, the neighbor on the other side of us, waddles out to feed her cats. A great lumbering woman who is all heart, as if her body had puffed out from it. Our dog ate one of her cats—well, killed it anyway. We don’t know exactly how many more she has over there. We expect our dog will find out. Cherise understands. She goes inside. She will come out at exactly 6:30 a.m., start the Subaru, and go to work. She will come home at exactly 5:20 p.m., park the car, and go inside. On Friday morning, half an hour before the garbage truck comes, she will put her trash in the can. One time, out of the blue, she asks us if we want some poppies. She says she has some bulbs from somewhere in Asia, then lowers her voice: You know, the funny kind. I instantly want to fill a bed in my front yard.

I’M SITTING ON THE COUCH, looking out the window, when I see a flash of woman emerge from a space across the street, the alley between a house going to shit and a house being flipped. Right behind her a flash of man. He is skinny with desperation, and she is skinny with fatigue. Both have the ashen flesh of heroin. I’ve seen them before; I can’t help feeling like I know them, in the dumbest way. They are always swearing, usually loud enough to be heard. She is always following him. Up the street, down, up again. I think of the word “cadaverous.” I used to think the closer to death you get, that’s where the life is. Now I watch from inside my house through a plate-glass window. I hear my husband pissing in the toilet, an ordinary sound, and all I can think is, Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Verge: Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Verge: Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Verge: Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.