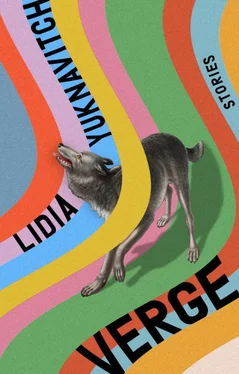

Лидия Юкнавич - Verge - Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Лидия Юкнавич - Verge - Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2020, ISBN: 2020, Издательство: Riverhead Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Verge: Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Riverhead Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2020

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-52553-487-7

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Verge: Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Verge: Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A fiercely empathetic group portrait of the marginalized and outcast in moments of crisis, from one of the most galvanizing voices in American fiction. cite

Verge: Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Verge: Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In her watervision, the swimmer feels the pull.

There is a pull for some people when they are in big water. A pull no one talks about. The pull comes to people whose lives are too weighted. People whose lives break the story and travel to realms everyone else fears. The pull is cool and warm at the same time; it releases a body back to history; it is something like amniotic fluid, only stronger. Most people who feel the pull let themselves go down a little, sink underwater some. They let their arms and legs go limp, and they close their eyes and hold their breath with a superhuman calm. The kind of calm that comes to those people who believe as children that they can breathe underwater. Those who feel the pull then experience one of two things. Some thrash toward exhaustion, then move toward a kind of motionless surrender, as the water enters what used to be their breathing, as it did before we were born. The pull lives in all of us differently.

Then there are the others, who open their eyes underwater and a rush of agency comes into them, much bigger than breath, and they bicep and kick their way back to the surface and pull air back into their lungs in a great gulp. They fight for life.

She removes her shoes in the raft. Her sister removes her shoes as well. She removes her pants. Her sister follows. She slides from the raft into the water. Her sister slides into the water after her. Two swimmers who learned to swim before they learned to walk.

The swimmer eyes the distance, her head a buoy on the surface of the sea. What would look much too far to a regular person—what looks terrifying, like a choice to drown, to the others on the boat—seems absolutely possible to her. She turns to look at her sister. She can see in her sister’s eyes that they can both make it. Treading water, her arms making figure eights and her legs pumping easily, she has no doubt in her body. They can swim to life. She reaches over and smooths her sister’s brow.

Then the sisters find the raft ropes and tie them to each other’s ankles.

With a phenomenal confidence, they swim for it, towing the others behind them. The beautiful bodies of the swimmer and her sister, and the great watery pull underneath, and the pull of the eyes and hearts of the people hoping against hope in the raft, and the pull of the great wrong world raging around them toward—

This story has no ending.

We put children into the ocean.

THE ORGAN RUNNER

For six months, when she was eight years old, Anastasia Radavic’s entire left hand was grafted to her ankle, just above her foot.

She’d been run over by a combine harvester in a wheat field, completely severing her hand from her arm. Though she’d worked in the fields with her family since she was five and was thus considered skilled as a laborer, a three-second glance away as the combine harvester passed her row of youths, their hands low to the ground, was time enough for the tragedy to occur. The hand was too badly damaged to reattach immediately, so the doctors attached it to her ankle to let it heal, a risky procedure for even the world’s best doctors. In her part of the world, the doctors were often newcomers, eager to hone their skill at the latest procedures in an area with plentiful patients and little regulation. Six months later, doctors reattached her hand to her wrist. It took several operations before the feeling returned, the pink color gradually improving with her blood flow, and eventually she regained some use in the hand. But she never forgot how it looked growing from her ankle. Two parts of her body seamed together in a way they should never have been. She remembered resting in a hospital bed, staring down at the handfoot, wondering if they told each other secrets.

At night the other children in the state hospital whimpered a little like animals, crying themselves to sleep, some of them more or less abandoned. This went on for months and months as Anastasia healed. She thought of her hand, lodged at her foot, and it made her think of chimps, the way they run with the backs of their hands to the ground and their feet grabbing at things for traction. Her dreams filled with primates; she imagined herself running with her hands.

Anastasia knew from school that the Soviets had used rhesus monkeys in their Bion satellite program in the 1980s and ’90s. She had even memorized their names: Abrek, Bion, Verny and Gordy, Dryoma and Yerosha, Zhakonya and Zabiyaka, Krosh and Ivasha, Lapik and Multik. Of them all, only Multik had died, slipping away while under anesthesia during a biopsy.

Anastasia spent nearly two years recovering at the state hospital, and she told any nurse who would listen about her fascination with the monkeys. One of them snuck her a book by a Western primatologist, Jane Goodall— My Life with the Chimpanzees , it was called—along with a small stuffed monkey. She slipped the book under her thin, stained mattress to keep it safe.

After her hand had healed as much as it was going to, she was released from the hospital, hiding the book beneath her waistband in the small of her back as she prepared to leave. The stuffed monkey—she’d named it Goodall—she carried openly; it was a child thing, and no one noticed or cared. She was sent back to a distant aunt who agreed to take her when her family didn’t show up. ( What use is a one-handed girl on a farm? her father had been heard to say. We have nothing but work here. ) She lived in a house with seventeen other children.

The distant aunt ( Was she? Anastasia wondered), as it happened, made her living from her body. Most of the children were hers. ( Were they? the girl wondered.) The aunt took great pride in the fact that she’d lost none of her children, to death or anything else. The children ranged in age from an infant, suckling at the woman’s breast, to a fourteen-year-old boy. But the aunt was aging, and that tilted the economy toward new endeavors.

Anastasia never returned to school. Instead, she quickly began learning the lessons of the house. As early as five years old, the aunt started instructing the children on a matter that was very important to their survival, or so they were told. The human body, they learned, has eight organs that can be donated to another body: the lungs, liver, heart, kidneys, pancreas, and small intestine. Tissue can also be donated, including skin, bone, tendons, cartilage, corneas, heart valves, and blood vessels. Some organs, including the liver, could be donated in sections. Sperm, breast milk, egg cells, hair. Everything of a body had worth.

After the middleman took his cut, roughly four percent of the donor price went to the organ runner. Four percent isn’t much, but multiplied by seventeen workers it meant everything. Enough to buy a new refrigerator or stove or car, enough to change things forever.

Anastasia made a place for herself in the house quickly by immediately abandoning self-pity (a luxury she’d given up the first time she watched her father backhand her mother nearly across the room) and securing a sleeping spot in the front room, in a nook carved into the stone wall near the fireplace—probably used in other centuries for cooking or keeping food warm or babies or hens or who knows what else. She shoved Goodall into the corner with some straw and made herself a pallet from old blankets and newspapers, not unlike the nests made by chimps she’d read about in the Jane Goodall book. It was a good space for a child and a stuffed monkey: safe from harm, warm, close to the door in case she needed to run.

Most of the other children seemed unfazed by her arrival, absorbing her into the organism of them. Except the oldest boy, Kiril, who decided that she was worth his ire, perhaps because she was new and a lame with her barely functioning hand. Children who move through life in packs are skilled at identifying the weak.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Verge: Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Verge: Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Verge: Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.