Was he looking for a specific haemophiliac family in the early 1860s? I doubt it. Had he been he’d have found one and taken the steps he took twenty years later at that time. Perhaps it didn’t occur to him. Or else it was only when he’d attained in almost anyone’s eyes – except his own? – spectacular worldly success, when he was the leading expert in his own field, a royal doctor, a professor, that he came to ask himself what in fact he had actually achieved. He had pioneered nothing, made no new discoveries, unless you can call confirming other people’s conclusions, such as the way haemophilia was carried and transmitted, a discovery. But suppose he had a haemophilia carrier in his own family? Suppose he had a haemophiliac of his own?

Did he at first dismiss the idea as monstrous? I’d like to think so, I’d like to think he had one redeeming feature. But I’ve no proof one way or the other. I’ve no proof of any of this except the knowledge that it has to be so, it’s the only explanation. I’m pretty sure that once the possibility had come into his mind it stayed there and grew, he couldn’t get rid of it even if he wanted to. He very likely told himself that if he lacked the courage to do it – for he saw only himself, only the great doctor, the Queen’s favourite, at the centre of everything – if he lacked the courage to do it, he’d regret this omission for the rest of his life. Control circumstances, that’s the answer.

The doorbell is ringing. Paul, of course, having once again forgotten his key. But it’s not Paul, it’s a man from the Maida Vale Society wanting my support in an effort to ban the two high towers they’re proposing to build at Paddington Basin. He wants to come in, he wants to ‘talk it through’ with me, and it’s in vain I protest that this is St John’s Wood, at least a mile away.

‘They’ll be visible from this house,’ he says, and as if this will clinch things. ‘They’ll be visible from Richmond!’

I haven’t the heart to tell him that the huge trees at the end of this garden block out any view as well as most of the light and air at the back. Instead I promise to write to my MP, the Mayor of London and a few Westminster councillors for good measure. He’s looking longingly at the whisky (or so I think) and suddenly I don’t want him to go, he seems rather nice, and I need someone there to talk to me, talk to me about anything, even planning authority solecisms, to keep me from Henry. But when I offer him a drink he says he can’t, he’s driving, and I realize it wasn’t the whisky he was eyeing but all my Henry stuff. He asks me what I’m writing.

‘Someone’s biography,’ I say but I don’t add, I was .

‘That must be very rewarding,’ he says rather wistfully.

‘Sometimes.’

I think to myself, when he goes Paul will come, I won’t have to be alone with these thoughts. As I let him out Paul will come and then Jude will come back. I’m a fool, aren’t I? It’s not my crime, my sin, my horror.

I go out on to the pavement with him and look tube station-wards down the square. There’s no one but an old lady exercising a Yorkshire terrier, no Paul and, of course, no Jude yet. The Maida Vale man gets into his car and drives off to his next port of call. I go indoors. Dusk is coming fast and if I went back now to look for my son I wouldn’t be able to see to the end of the street. What can Henry’s thoughts have been like at dusk, in the dark? When he was old, when he regretted what he’d done?

The idea was there when he was young and when he was in young middle-age but something had to happen to trigger it off, make it no longer a wild dream but a reality. The trigger may have been Dr Anton Hoessli’s publication of his Tenna conclusions in 1877 or it may have been Richard Hamilton’s death. Henry loved Hamilton and if he had been able to marry Hamilton’s sister – and so in a sense marry Hamilton in a way pleasing to society, binding himself to Hamilton for ever – the great idea might have remained what it was, the kind of horrible fantasy all of us have but never bring to fruition. The kind of fantasy I’ve had when I’ve hoped Jude would turn out to be irremediably barren or her child die. But Hamilton was killed in the Tay Bridge disaster. When that happened Henry may have thought that love and happiness were over for him and only ambition and acclaim for achievements mattered.

Two years later he was in love – or what passed for being in love for him – with Olivia Batho. At the same time he was conducting a typical Victorian gentleman’s liaison with Jimmy Ashworth. Neither of these relationships could be permanent, they got in the way of his grand design. It was time to pursue his researches into the haemophilia-carrying families further.

The phone rings and it’s Paul. A year ago he’d no more have phoned to say he was or wasn’t coming over than he’d have embraced me, something that does occasionally happen these days. He’s not coming but he’ll drop in tomorrow if that’s all right.

‘How’s Jude and my sisters?’

Did I say we now know for sure they’re both girls? I tell him they’re all fine. Jude’s round at the Croft-Joneses and I’m about to have a whisky. Oddly enough, I do feel like a drink now and I pour myself a large one worthy of Lachlan Hamilton. What did those Victorian gentlemen drink? I’ve never bothered to find out. Madeira, probably, and pints of sherry. Brandy, as Samuel Johnson says, is the drink for heroes.

Henry went back to Safiental, walking the twenty miles from Versam to Tenna, and began asking serious questions of the villagers. Haemophilia no longer affected anyone living there but it lingered on in men and women’s memories. This would have been in the spring of 1882. What he discovered was that a woman called Magdalena Maibach later called Barbla, had been taken from Tenna to Zurich and thence to Paris by her adoptive mother and benefactress. Barbla Maibach was worth pursuing. Her father was mentioned as a haemophiliac by Vieli and Grandidier and again by Hoessli, so therefore she must be herself a carrier. Henry believed the disease was in some mysterious way carried in the blood – what else? Perhaps, if his experiment succeeded, he’d find out just what that mysterious way amounted to.

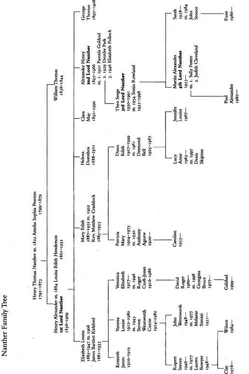

I don’t know how he discovered what had become of Barbla but with many European countries starting to keep birth, marriage and death records, it wouldn’t have been too difficult. It would have taken time, that’s all. In fact, it probably took him getting on for a year. He discovered that Barbla married a Thomas Dornford, a jeweller in Hatton Garden, and had several children. One of them married William Quendon and became the mother of a certain Louisa Quendon, now the wife of Samuel Henderson, a Bloomsbury solicitor.

Why go to all this trouble when part of his job was treating haemophiliac patients? Surely he could have picked the daughter of one of them. Easily, except that secrecy was of the essence. Who would believe that a doctor who warned the daughters of haemophiliacs not to marry and haemophiliacs themselves not to marry, would, in full knowledge of what he was letting himself in for, marry a woman who had a fifty per cent chance of being a carrier?

His diary tells me that in the spring of 1883 he went on a walking tour of the Lake District. I don’t believe it. He was more likely in Amsterdam, checking on the last stages of his hunt for Barbla and her descendants. His next step was to acquaint himself with the Henderson family. One way would have been to transfer his legal business to Samuel Henderson’s firm. There were a good many reasons not to do this. It was an obscure little partnership of three attorneys, struggling, not doing very well. For a man like Sir Henry Nanther to consult them would have looked odd, even suspicious. Besides, he had his own lawyers, eminent giants in their profession, the Mishcon de Reya of their day. Later on, of course, he did transfer his business but by then he was secure of a Henderson daughter. But for the present, the idea of staging an attack and a rescue appealed to his sense of drama. In any case, it was an excellent plan, guaranteed to earn him as rescuer the gratitude of Samuel Henderson and the approval of the whole family, besides providing him with an excuse to pay frequent visits to the house in Keppel Street.

Читать дальше