Barbara Vine - The Blood Doctor

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Barbara Vine - The Blood Doctor» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Blood Doctor

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

The Blood Doctor: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Blood Doctor»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Barbara Vine (a.k.a. Ruth Rendell) deftly weaves this story of an eminent Victorian with a modern yarn about the embattled biographer, who is watching the House of Lords prepare to annul membership for hereditary peers and thus strip him of his position. Themes of fate and family snake throughout this teasing psychological suspense, a typically chilling tale from a master of the genre.

From Publishers Weekly

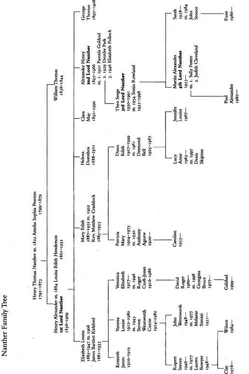

This rich, labyrinthine book by Vine (aka Ruth Rendell) concerns a "mystery in history," like her 1998 novel, The Chimney Sweeper's Boy. Martin Nanther-biographer and member of the House of Lords-discovers some blighted roots on his family tree while researching the life of his great-great-grandfather, Henry, an expert on hemophilia and physician to Queen Victoria. Martin contacts long-lost relatives who help him uncover some puzzling events in Henry's life. Was Henry a dour workaholic or something much more sinister? Vine can make century-old tragedy come alive. Still, the decades lapsed between Martin's and Henry's circles create added emotional distance, and, because they are all at least 50 years dead, we never meet Henry or his cohorts except through diaries and letters. Martin's own life-his wife's infertility and troubles with a son from his first marriage-is interesting yet sometimes intrudes on the more intriguing Victorian saga. Vine uses her own experience as a peer to give readers an insider's look into the House of Lords, at the dukes snoozing in the library between votes and eating strawberries on the terrace fronting the Thames. Some minor characters are especially vivid, like Martin's elderly cousin Veronica, who belts back gin while stonewalling about the family skeletons all but dancing through her living room. Readers may guess Henry's game before Vine is ready to reveal it, but this doesn't detract from this novel peopled by characters at once repellant and compelling.

From Library Journal

In her tenth novel writing as Barbara Vine, Ruth Rendell offers a novel of suspense based in 19th-century England and centering on deceit, murder, and various other family skeletons. Martin Nanther, the fourth Lord Nanther, has a comfortable life in present-day London as a Hereditary Peer in the House of Lords and as a historical biographer. He chooses as his most recent subject his own great-grandfather, the first Lord Nanther, physician to the royal family (Victoria and Albert) and an early noted researcher into the cause and transmission of hemophilia. The reader is taken through the family history as Martin painstakingly uncovers some not so savory bits of his own family's past. The story is dense with characters, and the author provides family trees of the two principal families, for which any reader will be eternally grateful. The story lacks the usual page-turner suspense of the Rendell/Vine novels but makes up for that with unusually detailed glimpses into Victorian life and the inner workings of the House of Parliament, which American readers will find particularly intriguing. Recommended for all public libraries. Caroline Mann, Univ. of Portland, OR