I was mystified. What could there be that was so unfortunate about being the daughter, or come to that the son, of the prosperous Caspar Raven of Raven’s Bank and his wife Olivia? Poor old Farrow’s eyes were suddenly very bright, as if full of unshed tears. But surely not. I saw him then, and I was right, as the devoted son of a possessive mother who, when the mother grew old and perhaps senile, married a wife to be a mother substitute when the time came. The tears were held back but the voice faltered a little.

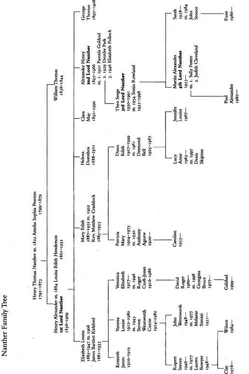

‘I see you don’t know,’ he said. ‘Olivia had a lover, they’d call him a boyfriend these days. She ran away from her husband and deserted her three children. She went off with a man whose name I can’t remember – Vi would know. My grandfather obtained a divorce, very difficult in those days but not so hard since the divorce law was passed a few years before, and of course there was no question of Olivia having the children. They had a sad time of it.’

‘When was that?’

‘In eighteen ninety-six. My mother was five, her sister was seven but the little boy was only two. My grandfather, Caspar that is, had a very savage temper, though it really only came out after his wife left him. Before that he worshipped the ground she trod on, Mummy said, would have done anything for her. He took it out on the children later and, as I said, they had a sad time of it.’

I asked him what happened to Olivia. Did she marry the man? Instead of answering, he asked me if I was ‘familiar with the works of Oscar Wilde’. Pretty well, I said.

‘He’s supposed to have based his Lady Windermere on my grandmother, only my grandmother did run away with her man and Lady Windermere didn’t. As to what happened to her, she didn’t marry the man, I don’t know what he was called, but moved in with another one and another. This was in France, somewhere in the south of France. My grandfather knew, he told his children all about it, in the most savage way. Olivia came back here just before the Great War. My mother was grown up by then and she sometimes visited her, unbeknownst to her father of course. When Olivia died in nineteen twenty-four they found she had a heart defect you only get if you’ve contracted syphilis at some time or other.’

While I resolved to check up on Lady Windermere’s Fan because I’m not sure the dates tally, he was picking up the photographs and putting them back in his briefcase. ‘Look, I’m going home now. It’s only Hammersmith. Why don’t you come back with me and talk to my wife?’

7

Often ahead of his time with his discoveries, Henry had postulated in the early spring of 1882, in a paper he gave to the Royal Society, that two factors contribute to the clotting of blood. Calcium was one of them and what he called ‘thromboplastase’ the other. He was wrong but he was heading in the right direction. Twenty years were to pass before the four factors and two products theory came into being and many more before medical science understood that the factors concerned in the activation of prothrombin by thromboplastin were twelve in number, all finally to be designated by roman numerals.

None of this is the interesting stuff of biography but it will have to go in so that readers understand how Henry strove to be a pioneer in his field. The dull with the exciting, the rough with the smooth. He seems to have worked hard, to have put his whole heart and soul into his studies and his practical work, but to have known too that change and rest were essential for him. His walking holidays were a high point of his year. The trip abroad he took in the last week of April 1882 began in Chur, Cuera in Romansch, the oldest town in Switzerland, now a ski resort, in the southeast corner of the country. This may have been familiar territory to him, recalling his time at the University of Vienna when he first grew to love the Alps.

From Chur he seems to have set off to walk the mountain paths of the Hinterrein. There was no Richard Hamilton to accompany him and no Hamilton to write to now. Did he miss Hamilton, his companion on so many walking tours in the past? He must have, perhaps bitterly. From a village high up in the mountains, where he boarded at the home of the Schiele family, he wrote to that other medical friend he seems to have become acquainted with at Barts, Lewis Fetter:

My dear Fetter,

This is as remote a place as I was led to believe it would be, a mere scattering of houses on the south-eastern meadow slopes of the Graubünden. Very beautiful if one’s tastes tend to the picturesque. Communication between these houses and the outside world must be established over broken and dangerous tracts ofland. No driving roads exist. Fortunately, as you know, I have always been a walker and am undeterred by the prospect of covering several miles on foot. As it happened, I was obliged to make a journey of six hours to reach here from Versam, a distance I calculate as no less than twenty miles. You may believe me when I say I was heartily glad to reach the quaint and picturesque house inhabited by the good Schieles, to find a meal of roast meat, potatoes and a kind of fruit porridge awaiting me, its consumption followed by rest in a comfortable bed in a clean and airy room.

The snows are gone except from the highest peaks and the alpine meadows bursting into glorious bloom. This village is much exposed to the weather, but sunshine and a dry atmosphere render it a healthy place. Except, according to V and G, as you know, in one respect. Still, all that is in the past now. Presently, the population consists of about a hundred and fifty persons, healthy and sturdy people for the most part. Pleurisy, pneumonia and arthritis deformans are, however, common. Scurvy and purpura are unknown and phthisis rare…

The rest of the letter is concerned with compliments to Fetter’s family, enquiries after his own health and assurances that he, Henry, will be ‘back in Wimpole Street by the twelfth of May’. He heads his letter Safiental, Graubünden. Who are or were V and G? Friends Henry and Fetter had in common? Or could they be authorities on public health at the time? Could V be the Dr Vickersley who was one of the guests at Henry’s dinner party the following September?

If Henry also wrote to Olivia Batho or Jimmy Ashworth, his letters haven’t turned up but, knowing his character as I’m starting to, I’m inclined to think he didn’t write to either of them. Henry was a disciple of the Byron School and would have agreed that ‘man’s love is of man’s life a thing apart’.

I didn’t go home to Hammersmith with Stanley Farrow that evening. I was taking Jude out to dinner. I stopped on the way home and bought red roses, for no reason except that she likes them. Stanley eventually renewed his invitation. He seems to take his role and function as a working peer for the Government lightly as some of them do, coming in for questions and disappearing before the ordeal of staying behind to vote, and often not coming in at all. Of course he may have been there on the few days I wasn’t. It was well into February before we encountered each other again. I was having a cup of tea in the Bishops’ Bar, when he came over to me, said Vi was ‘dying’ to meet me and would I like to bring my wife for dinner? I made such a mess of refusing that he must have been left with the impression my marriage was unhappy and that Jude and I led completely separate lives. In the end I said I’d come on my own, but for a drink, not dinner.

The day I went I’d received in a parcel the letters Henry wrote to Barnabus Couch. It rather shocked me, that their possessor risked sending them by post, even though by recorded delivery. The sender, a Mrs Deborah Couch, widow of Henry’s friend’s great-grandson, was not to know that Henry made copies of every letter he ever wrote. After her husband’s death, she’d found the letters neatly packed, wrapped in sheets of newspaper ( The Times , of a date some time in August 1906) when she was turning out the attics of the old rectory where they’d lived. They were a dozen among hundreds. Couch had had a voluminous correspondence and apparently kept every letter he’d received, instructing his unmarried daughter, according to Mrs Couch, just prior to his death, to ‘preserve them all or, by God, I’ll come back and haunt you’. It’s a strange thing but I’ve often noticed how upset otherwise quite rational people can be by this threat.

Читать дальше