I order coffee and ask him how his mother is. All right, he says, or so he supposes. Sally has been living for the past year in a self-supporting community in the Outer Hebrides and Paul says he never writes letters, only e-mails, which, he says, puts her outside his remit. No one, anyway, could expect him to travel to a remote Scottish island in April even if he could afford the train fare. We asked him to Alma Villa for the Easter holiday, it is after all his home, but he prefers staying in a friend’s flat in Ladbroke Grove, something I understand perfectly.

‘Can I have pudding?’ he says, like a little boy.

It moves me, just as it does on the rare, the very rare, occasions when he calls me dad. I want to hug him the way I did before Sally left and took him away, but that of course is out of the question now and for ever. The sweet trolley comes round and he has profiteroles in chocolate sauce. Paul is taller than I am and much better looking. I notice the other diners, peers and their wives and women peers and husbands, stealing glances at him. There’s a former prime minister sitting at a table under the portrait of Henry VII. He’s spotted Paul, recognized him and favoured him with a wave and a nod. Thank God Paul smiles back and dips his head. I suspect it’s ironic but no one else does.

The time is approaching a quarter past two and things are speeding up because the House sits at two-thirty. Everything is run with exquisite precision in here, the organization superb and nothing neglected or forgotten; coffee served in plenty of time for peers to drink it, pay their bills – or pay them tomorrow or next week – and amble off towards the Peers’ Lobby and the Chamber. No rush, no urgency and no unpunctuality. Maria has passed our table, given me the smile that indicates nothing could be further from her thoughts than expecting me to pay before next week, and Farouk has removed Paul’s plate. We get up.

Last time I brought Paul in here he was sixteen, shyer and less confident than he is now. The doorkeepers called him ‘the Honourable Paul Nanther’, gave him the book to sign and showed him to the steps of the throne, where peers’ eldest sons sit by right.

In one way I’d like Paul to come into the Chamber. I’d be proud of him sitting on that step, which is really a padded seat, his back against that towering structure, such a bright gold it hurts the eyes to look at it for long, beneath that spiritual oddity the Cloth of Estate and below the hallowed chair where only the reigning monarch may be seated. After half an hour, after question time; I’d catch his eye and we’d go out together. On the other hand, I’d be afraid he might do something, misbehave himself in some way. Not shout, not make some inflammatory statement so that he had to be bundled out, but put his head in his hands or favour the House with that look he’s bestowing on me now as we walk down the corridor towards the Prince’s Chamber, supercilious, critical, slightly incredulous. It tells me he’s rejecting the steps of the throne this time. It’s very likely his last chance but he won’t care about that.

‘I’d better go, Dad,’ he says, and of course my heart goes out to him. I want him to stay. That I’ve got an appointment at four with two people I really want to see alone weighs nothing with me. I ask him if he’s sure he doesn’t want to come into the Chamber.

‘Not much point, is there?’ he says in a sulky way. ‘I soon shan’t be able to,’ he complains, as if I’m personally responsible for the reform bill.

I walk downstairs with him and outside the Peers’ Entrance renew our invitation to come and stay at Alma Villa whenever he likes. Thanks, he says, but he’s fine where he is and spoils a perfectly reasonable form of refusal by adding that he doesn’t suppose Jude and I want anyone else around. I’ve noticed that lately he’s begun talking about us as if we were still on our honeymoon or a couple of teenage lovers who’ve just moved in together. The last I see of him he’s standing in front of the lavishly robed statue of George V on the far side of the street, giving it I suppose one of his incredulous looks. But he has his back to me and I can’t see his face.

I call in at the Printed Paper office, pick up yesterday’s Hansard and go into the Chamber during the first starred question, seating myself behind Lord Quirk and in front of Lord Northbourne. I’m not very interested in the question so I discreetly read the record of yesterday’s proceedings. You may read in here so long as it’s not a book or a newspaper, which are severely frowned on and may be confiscated. Hansard is all right. In 1877 a Treasury grant had been made to the Hansard firm enabling them to employ four reporters and report more fully than had been the case when the volumes were mostly compiled from newspaper reports. Henry was introduced in 1896 but it wasn’t for another thirteen years that Hansard became the Official Report and its text ‘full’. By then Henry was dead. Still, the relevant ‘Parliamentary Debates’ are quite adequate to show me the few times he spoke after his maiden speech. I look up and picture him somewhere on the spiritual side when the Tories were in power, proud of himself perhaps but a little uneasy too because the peers on either side of him are of ancient lineage and his peerage is of first creation. Is it only the English or only Europeans who rate blood (genes now, Henry, DNA) more highly than achievement?

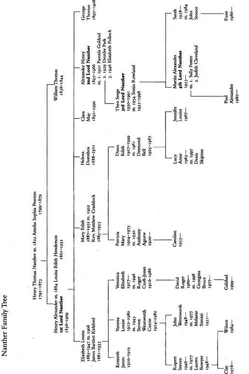

When I’d decided to write Henry’s biography I advertised in The Times , the Spectator , the Author and a good many other places, for descendants of people who’d known him, who possessed letters from him or letters and documents in which he was mentioned. The advertisement I put in The Times is still going and may still, I’m hoping, summon up further information. Of course I’ve had dozens of responses. It’s been largely a matter of sifting through them for what’s useful and what isn’t. Among the people who replied were the two women who are coming in this afternoon. They didn’t sound likely readers of The Times but the younger one explained she was told about it by her son.

I’ll have to go back into the Chamber sometime, but not yet. The Salisbury Room beckons and I make my way quietly down there and sink into one of the slippery leather chairs. These chairs, especially the low black ones, seem designed to keep an occupant from falling asleep, their backs being too short for comfort and their seats too long. A bearded Lord Salisbury, or a bust of him, looks through me towards the river and St Thomas’s Hospital, and that reminds me that no one’s allowed to die in the House. It’s supposed to be something to do with the Queen’s coroner having to preside at the inquest on anyone dying in a royal palace and that being too difficult or too expensive or, as my son might say, whatever. Anyone who does die is carted off by ambulance to St Thomas’s and pronounced dead on arrival.

I read my Hansard and then I read my Guardian as devotedly as if I sat on the Government benches. The Guardian reminds its readers of the Salisbury Convention – appropriate for this room – which postulates that any intention a political party presents in its manifesto shall be taken as the will of the people if that party is voted into government. Somehow, I don’t think that rule is going to cut much ice with the opposition when it comes to the sitting and voting rights of hereditary peers, though the Government plainly set out that it intended to abolish their parliamentary right.

I think back over the records of my forebears. Henry did his bare duty, made a maiden speech, came in sometimes, occasionally spoke, and Alexander seldom attended. Of course he was only fourteen when he inherited but, though living in England for a while after coming out of the army in 1918, he seems to have shown his face in here only once before he went off to the South of France, and only a couple of times in the thirties. He must have found it trying, not being permitted to smoke in the Chamber. My father was dutiful. It’s an advantage to be a lawyer in Parliament and he made an eloquent maiden speech presenting the humane case for the abolition of the death penalty. Afterwards he came in regularly once a week, though he never said any more, apart from occasionally intervening with a supplementary at question time. I’ve attended regularly, but I doubt if I’ve contributed anything memorable or that my absence, after the Bill becomes the Act, will be much noticed.

Читать дальше