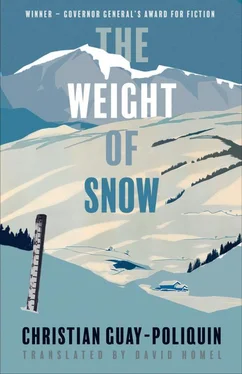

I continue following Matthias’s tracks. They lead to a small network of paths that run from one house to the next. The village is frozen solid, and only three chimneys have smoke coming from them.

In front of me, at the end of the street, I spot a figure. I don’t think it is Matthias, but I want to be sure. I wish I had brought my spyglass. The person disappears down a side street. Whoever it is has not seen me. Unless they are pretending not to.

Further on I recognize the house that lost its roof in the fire. The charred rafters stand out against the whiteness of the snow, and the ice has given them a striking lustre, black and luminous. As if winter were toying with a burned skeleton that did not receive proper burial.

I cross the bridge to the centre of the village. A ray of sun shines through, and for a moment the air seems milder. Near the town hall, in the golden light, a man is leaning against a tree. I squint. It’s Jonas. I recognize his turquoise coat. I move toward him. My leg is giving me serious pain. I’m going to need to take a rest. When I reach him, Jonas gives me a mocking look.

I saw you coming, he says, chewing on something. You walk so slow, you give everyone time, everyone time, to see you coming.

What are you eating? I ask, sitting down in the snow.

Pemmican, he tells me, and proudly displays the piece he is holding in his hand. Matthias gave it to me. It’s good, really good pemmican. There’s not much meat left in the village. No one can go hunting. There are no guns anywhere. We looked everywhere. Jude and the others took them all. No one knows when they’re coming back. But I don’t want anyone to kill any more cows. I’m the one who takes care of them. I feed them, I clean the stalls, and they keep the stable warm. I sleep real good in the hay.

Where did he go?

Who?

Matthias, I say, trying to catch his eye, Matthias.

He came from that way. We talked. He promised me he’d give me more pemmican if I helped him find some gas. I told him I’d see what I can do. It’s easy, there’s some at Jude’s place. Eight canisters and I’m the only one who knows where they are. That’s going to be a lot of pemmican.

Where did he go?

I don’t know, I think he went toward the arena. But watch out, don’t go, don’t get too close to the arena. The snow, the roof collapsed, and parts of the wall are falling, piece by piece, and they don’t warn you first.

Jonas leans over and stares at me, scratching his head.

You’re going to catch cold sitting on the ground, he warns me.

He helps me to my feet and hands me my ski poles.

Anyway, winter, winter is coming to an end. The river has started to break up. You don’t see it, but you can hear it. If you know how to listen.

For a time we say nothing. Total silence.

It’s getting humid. Last night there was a halo around the moon. It’s going to snow pretty soon. A snowstorm, just one more, then it’s going to start melting. And after, after the snow, when the roads are clear, I’m going to be able to sell my bottles.

Where? I ask him, smiling.

On the coast somewhere, in a grocery store.

Jonas’s face shines, then a shadow falls over him.

I have a lot of bottles. And they’re heavy. I’ll need a car. And I don’t know, I don’t know how to drive. And I don’t have a licence. Matthias promised, he promised to take me there if I find him some gas. Do you think I can trust him?

I clear my throat.

I’m sure, I say, looking at the church a little further on, that he’s a man of his word.

Jonas’s face lights up again. He smiles at me, slips his pemmican back into his pocket, and moves off.

I evaluate the condition of my left leg. The rest did me good. The pain is stable. I can keep on.

As I head for the arena, the clouds knit together above the village and the landscape turns dull. In front of the church, I notice snowshoe tracks. I look up. One of the doors is ajar. I go to the entrance. Without a sound, I ease my head through the doorway.

It’s dark inside, but the grey light of day passes through the dull stained-glass windows. On one of the pews, close to the altar, I recognize Matthias, his bent shoulders. He is on his knees. I believe he is praying.

I retreat and walk quickly away from the church. I hide behind the rectory. This way, he won’t be able to see me. And I will be able to follow his next move.

It is not very cold, but since I am not moving, my limbs and the muscles of my face have gone numb. I start sneezing. Every time I do, I am afraid Matthias will step out of the church and see me.

The door finally opens, and Matthias comes out. He looks around, then follows the path. I let him get ahead of me, counting to ten, then start to tail him. I hide behind trees that have fallen under the weight of the ice, telephone poles, and the corners of houses. I suspect he isn’t the kind of man who keeps looking back, but you never know.

Despite his age he moves quickly, and I have to work to keep up. I lose sight of him near the arena. I stop and wait and look at the building, a prisoner of the snow. It has become a heap of twisted metal buried beneath an avalanche of silence. Like the porch, but on a bigger scale. Not a shipwrecked vessel, but a great steamship that has struck an iceberg.

Snow begins to fall. The flakes are delicate, as if they have been ground to powder inside the clouds.

I continue to trail Matthias. As I go past the arena, I spot him entering a house. I stop and wait. It is the third house on the left, before the edge of the village. The house with the garage. The one where Joseph grew up. Like the others it seems to have been abandoned, and some time ago. I move forward carefully, leaving tracks in the soft snow, and suddenly I feel very far from the living room and the fireplace. If I go in and Matthias sees me, he will fly into a rage, and I do not have the strength to calm him down. Or run for my life. I circle the house, peering into the windows, but it is dark inside, and I can’t tell if he is there. I retrace my steps and notice a small pane of glass on one side of the garage. Snow covers part of it and I have to kneel down to look in.

I look, but don’t see much. Matthias is behind a car. He opens the trunk and leans in. He rummages through a large black suitcase. A shiver runs through me. He is sorting pemmican, canned goods, boxes of cookies. He is taking notes on a scrap of paper and counting on his fingers. When he finishes he gets in behind the wheel, takes out his key ring, and stares at the plastic moose hanging from it. He starts the engine and lets it idle for a while. His eyes shine, as if one of his wishes were about to come true. Then he cuts the motor, sets a photo on the dashboard, and begins to pray.

I sigh. It is all so predictable. I did not need to come this far to understand. Matthias is preparing his departure. I won’t be able to stop him. I am jealous – it is that simple.

When I stand up again, I can hardly feel my leg. I rub it, exercise it, but to no effect. When I tighten the straps on my snowshoes, I feel like I am leaning on a phantom limb, but after a few minutes of walking, the feeling returns little by little. And with it the pain.

The tracks I have left are visible for all to see. I can only hope the falling snow will conceal them from Matthias.

I move past the arena again, then the church. I cross the bridge and trudge down the main street. My leg is hurting. A sudden wave of fatigue overtakes me. I will need to rest before making the climb back to the house. Rest and warm up.

I choose one of the paths that leads toward a house that seems inhabited, even if no smoke is rising from the chimney. As I draw near, the snow weighing upon the roof makes my head spin. I take off my hat and scarf so my face is visible, and I knock on the door and wait. On the porch are several cords of wood, tall and tightly stacked. I knock harder. No answer. I open the door.

Читать дальше