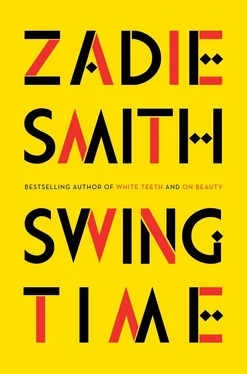

Zadie Smith - Swing Time

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Zadie Smith - Swing Time» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: NYC, Год выпуска: 2016, ISBN: 2016, Издательство: Penguin Publishing Group, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Swing Time

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Publishing Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- Город:NYC

- ISBN:978-0-39956-431-4

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Swing Time: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Swing Time»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dazzlingly energetic and deeply human,

is a story about friendship and music and stubborn roots, about how we are shaped by these things and how we can survive them. Moving from northwest London to West Africa, it is an exuberant dance to the music of time.

Swing Time — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Swing Time», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Better I find somewhere else. Yes, it’s better. This afternoon I look at a place in…” I heard papers being sadly shuffled. “Well, it doesn’t matter. Midtown somewhere.”

“Fern, you don’t know this city — and you don’t want to pay rent here, believe me. Take the room. I’ll feel shitty about it if you don’t. I’ll be at Aimee’s day and night — she’s got that show in two weeks, we’ll be up to our ears. I promise you — you’ll hardly see me.”

He closed a window, the river winds stopped rushing in. The quiet was unhelpfully intimate.

“I like to see you.”

“Oh, Fern… Please just take the room!”

That evening the only sign of him was an empty coffee cup in the kitchen and a tall canvas rucksack — the kind a student packs for a year off — leaning in the doorframe of his empty room. As he’d climbed the steps of the ferry with this single bag on his back, Fern’s simplicity, his frugality, had seemed to have something noble in it, I’d aspired to it, but here in Greenwich Village the idea of a forty-five-year-old man with a single rucksack to his name struck me as merely sad and eccentric. I knew he’d crossed Liberia, alone and on foot, aged only twenty-four — it was some kind of homage to Graham Greene — but now all I could think was: Brother, this city will eat you alive . I wrote a pleasant and neutral note of welcome, tucked it under the straps of his bag and went to bed.

I was right about barely seeing him: I had to be at Aimee’s for eight each morning (she woke daily at five, to exercise for two hours in the basement followed by an hour of meditation) and Fern always slept in — or pretended that he did. In Aimee’s townhouse all was frantic planning, rehearsal, anxiety: the new show was in a mid-size venue, she’d be singing live, with a live band, things she hadn’t done in years. To keep out of the line of fire, the meltdowns, the arguments, I stayed as much as I could in the office and avoided rehearsals whenever possible. But I gathered some kind of West African theme was afoot. A set of atumpan drums were delivered to the house, and a long-necked kora , swathes of kente, and — one fine Tuesday morning — a twelve-person dance troupe, African-by-way-of-Brooklyn, who were taken to the basement studio and didn’t emerge till after dinner. They were young, mostly second-generation Senegalese, and Lamin was fascinated by them: he wanted to know their last names and the villages of their parents, chasing down any possible connection of family or location. And Aimee was glued to Lamin: you couldn’t talk to her alone any more, he was there at all times. But which Lamin was it? She thought it very provocative and funny to tell me he still prayed five times a day, in her walk-in closet, which apparently faced Mecca. Personally I wanted to believe in this continuity, in this part of him still beyond her reach, but there were days I barely recognized him. One afternoon I brought a tray of coconut waters down to the studio and found him, in his white shirt and white slacks, demonstrating a move I recognized from the kankurang, a combination of side-stamp, shuffle and dip. Aimee and the other girls watched him carefully and repeated the movements. They were sweating, dressed in crop tops and ripped unitards, and were pressed so closely to him and each other that each movement he made looked like a single wave passing through five bodies. But the truly unrecognizable gesture was the one that swept a bottle of coconut water from my tray, without a thank-you, without the vaguest acknowledgment — you’d have thought he’d been taking drinks from the wobbling trays of serving girls every day of his life. Maybe luxury is the easiest matrix to pass through. Maybe nothing is easier to get used to than money. Though there were times when I saw a haunted quality in him, like he was being stalked by something. Wandering into the dining room toward the end of his visit, I found him still at the breakfast table, talking at Granger, who looked very weary, as if he’d been there a long time. I sat down with them. Lamin’s eyes were fixed somewhere between Granger’s shaved head and the opposite wall. He was whispering again, a perplexing, uninflected speech that ran on like an incantation: “… and right now, our women are sowing the onions in the right-hand beds and then the peas in the left-hand beds, and if the peas are not irrigated in the correct way then when they will come to rake the ground, about two weeks from now, they will have a problem, there will be an orange curl to the leaf, and if it has this curl, then it has the blight and then they will dig up what has been sown and re-sow the beds, making sure I hope to put a layer of this rich soil we get from upriver, you see, when the men go upriver, about a week from now, when we travel up there we get the rich soil…”

“Uh-huh,” Granger was saying, every other sentence. “Uh-huh, Uh-huh.”

Fern made sporadic appearances in our lives, at board meetings or when Aimee required his presence to deal with practical problems related to the school. He looked pained at all times — physically winced whenever we made eye contact — and advertised his misery wherever he went, like a man in a comic with a black cloud above his head. In front of Aimee and the rest of the board he gave a pessimistic update, focused on recent aggressive statements of the President’s, concerning foreign presence in the country. I’d never heard him talk like that before, so fatalistically, it was not really in his character, and I knew I was the true, oblique target of his critique.

That afternoon in the apartment, instead of hiding in my room as usual, I confronted him in the hall. He’d just come back from a run, sweating, bent over, with his hands on his knees, breathing hard, looking up at me from under thick brows. I was very reasonable. He didn’t speak but seemed to take it all in. Without his glasses his eyes looked enormous, like a cartoon baby’s. When I finished he straightened up and bent the other way, pushing the small of his back forward with both hands.

“Well, I apologize if I embarrassed you. You are right: it was unprofessional.”

“Fern — can’t we be friends?”

“Of course. But you also want me to say: ‘I am happy we are friends’?”

“I don’t want you to be unhappy.”

“But this is not one of your musicals. The truth is I am very sad. I wanted something — I wanted you — and I didn’t get at all what I wanted or hoped and now I am sad. I will get over it, I suppose, but for now I am sad. Is it OK for me to be sad? Yes? Well. Now I shower.”

It was very difficult for me, at the time, to understand a person who spoke like that. It was alien to me, as an idea — I hadn’t been raised that way. What response could such a man — the type who gives up all power — possibly expect from a woman like me?

I didn’t go to the show, couldn’t face it. I did not want to stand in the bleachers with Fern, feeling his resentment while watching funhouse versions of the dances we had both seen at their source. I told Aimee I was going and I intended to go but when eight o’clock rolled around I was still in my house sweats, lying half propped up on my bed with my laptop over my groin, and then it was nine o’clock, and then it was ten. I absolutely had to go — my mind kept repeating this fact to me and I was in agreement with it — but my body freeze-framed, felt heavy and immovable. Yes, I must go, that was clear, and just as clear was the fact I was not going anywhere. I got on YouTube, skipped from dancer to dancer: Bojangles up the stairs, Harold and Fayard on a piano, Jeni LeGon in her swishing grass skirt, Michael Jackson at Motown 25 . I often ended up at this clip of Jackson, although this time as he moonwalked across the stage, the thing that really interested me was not the crowd’s ecstatic screams or even the surreal fluidity of his movements but the shortness of his trousers. And still the option of going did not seem lost or completely closed until I looked up from my aimless surfing and found eleven forty-five had happened, which signified we were now in the undeniable past tense: I hadn’t gone. Search Aimee, search venue, search Brooklyn dance troupe, image search, AP wire search, blog search. At first simply out of a sense of guilt, but soon enough with the realization that I could reconstruct—140 characters at a time, image by image, blog post by blog post — the experience of having been there, until, by one a.m., nobody could have been there more than me. I was far more there than any of the people who had actually been there, they were restricted to one location and one perspective — to one stream of time — whereas I was everywhere in that room at all moments, viewing the thing from all angles, in a mighty act of collation. I could have stopped there — I had more than enough to give a detailed account of my evening to Aimee in the morning — but I didn’t stop. I was compelled by the process. To observe, in real time, the debates as they form and coalesce, to watch the developing consensus, the highlights or embarrassments identified, their meanings and subtexts accepted or denied. The insults and the jokes, the gossip and rumor, the memes, the Photoshop, the filters, and all the many varieties of critique given free rein here, far from Aimee’s reach or control. Earlier in the week, watching a costume fitting — in which Aimee, Jay and Kara were being dressed up to resemble Asante nobles — I’d hesitantly brought up the matter of appropriation. Judy groaned, Aimee looked at me and then down at her own ghost-pale pixie frame wrapped in so much vibrantly colored cloth, and told me that she was an artist, and artists have to be allowed to love things, to touch them and to use them, because art is not appropriation, that was not the aim of art — the aim of art was love. And when I asked her whether it was possible both to love something and leave it alone, she regarded me strangely, pulled her children into her body and asked: Have you ever been in love?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Swing Time»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Swing Time» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Swing Time» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.