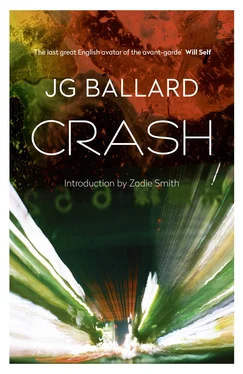

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

4thestate.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape in 1973

Copyright © J. G. Ballard 1973, 1995

Introduction copyright © Zadie Smith 2014

‘The Road to Crash’ © Travis Elborough 2008

‘Autopia’, first published in Drive magazine in 1971 and subsequently in The User’s Guide to the Millennium (1996) © J. G. Ballard 1971

The right of J. G. Ballard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007287024

Ebook Edition © 1973 ISBN: 9780007324309

Version: 2014-07-03

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Author’s Note

Introduction by Zadie Smith

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

THE ROAD TO CRASH by Travis Elborough

AUTOPIA by J. G. Ballard

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

THE MARRIAGE OF reason and nightmare that has dominated the 20th century has given birth to an ever more ambiguous world. Across the communications landscape move the spectres of sinister technologies and the dreams that money can buy. Thermo-nuclear weapons systems and soft-drink commercials coexist in an overlit realm ruled by advertising and pseudo-events, science and pornography. Over our lives preside the great twin leitmotifs of the 20th century – sex and paranoia.

Increasingly, our concepts of past, present and future are being forced to revise themselves. Just as the past, in social and psychological terms, became a casualty of Hiroshima and the nuclear age, so in its turn the future is ceasing to exist, devoured by the all-voracious present. We have annexed the future into the present, as merely one of those manifold alternatives open to us. Options multiply around us, and we live in an almost infantile world where any demand, any possibility, whether for life-styles, travel, sexual roles and identities, can be satisfied instantly.

In addition, I feel that the balance between fiction and reality has changed significantly in the past decades. Increasingly their roles are reversed. We live in a world ruled by fictions of every kind – mass-merchandizing, advertising, politics conducted as a branch of advertising, the pre-empting of any original response to experience by the television screen. We live inside an enormous novel. It is now less and less necessary for the writer to invent the fictional content of his novel. The fiction is already there. The writer's task is to invent the reality.

In the past we have always assumed that the external world around us has represented reality, however confusing or uncertain, and that the inner world of our minds, its dreams, hopes, ambitions, represented the realm of fantasy and the imagination. These roles, it seems to me, have been reversed. The most prudent and effective method of dealing with the world around us is to assume that it is a complete fiction – conversely, the one small node of reality left to us is inside our own heads. Freud's classic distinction between the latent and manifest content of the dream, between the apparent and the real, now needs to be applied to the external world of so-called reality.

Given these transformations, what is the main task facing the writer? Can he, any longer, make use of the techniques and perspectives of the traditional 19th century novel, with its linear narrative, its measured chronology, its consular characters grandly inhabiting their domains within an ample time and space? Is his subject matter the sources of character and personality sunk deep in the past, the unhurried inspection of roots, the examination of the most subtle nuances of social behaviour and personal relationships? Has the writer still the moral authority to invent a self-sufficient and self-enclosed world, to preside over his characters like an examiner, knowing all the questions in advance? Can he leave out anything he prefers not to understand, including his own motives, prejudices and psychopathology?

I feel myself that the writer's role, his authority and licence to act, have changed radically. I feel that, in a sense, the writer knows nothing any longer. He has no moral stance. He offers the reader the contents of his own head, a set of options and imaginative alternatives. His role is that of the scientist, whether on safari or in his laboratory, faced with an unknown terrain or subject. All he can do is to devise various hypotheses and test them against the facts.

Crash is such a book, an extreme metaphor for an extreme situation, a kit of desperate measures only for use in an extreme crisis. Crash , of course, is not concerned with an imaginary disaster, however imminent, but with a pandemic cataclysm that kills hundreds of thousands of people each year and injures millions. Do we see, in the car crash, a sinister portent of a nightmare marriage between sex and technology? Will modern technology provide us with hitherto undreamed-of means for tapping our own psychopathologies? Is this harnessing of our innate perversity conceivably of benefit to us? Is there some deviant logic unfolding more powerful than that provided by reason?

Throughout Crash I have used the car not only as a sexual image, but as a total metaphor for man's life in today's society. As such the novel has a political role quite apart from its sexual content, but I would still like to think that Crash is the first pornographic novel based on technology. In a sense, pornography is the most political form of fiction, dealing with how we use and exploit each other, in the most urgent and ruthless way.

Needless to say, the ultimate role of Crash is cautionary, a warning against that brutal, erotic and overlit realm that beckons more and more persuasively to us from the margins of the technological landscape.

1995

Introduction by Zadie Smith

I met J. G. Ballard once – it was a car crash. We were sailing down the Thames in the middle of the night, I don’t remember why. A British Council thing, maybe? The boat was full of young British writers, many of them drunk, and a few had begun hurling a stack of cheap conference chairs over the hull into the water. I was twenty-three, had only been a young British writer for a couple of months, and can recall being very anxious about those chairs: I was not the type to rock the boat. I was too amazed to be

Читать дальше