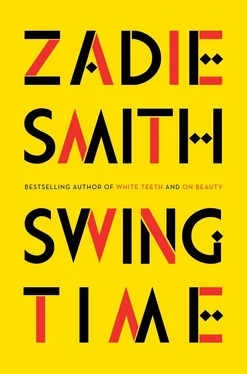

Zadie Smith - Swing Time

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Zadie Smith - Swing Time» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: NYC, Год выпуска: 2016, ISBN: 2016, Издательство: Penguin Publishing Group, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Swing Time

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Publishing Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- Город:NYC

- ISBN:978-0-39956-431-4

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Swing Time: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Swing Time»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dazzlingly energetic and deeply human,

is a story about friendship and music and stubborn roots, about how we are shaped by these things and how we can survive them. Moving from northwest London to West Africa, it is an exuberant dance to the music of time.

Swing Time — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Swing Time», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Oh, bravo. ”

I hurried to her, apologizing. She opened the door: “Just get in.”

I sat next to her, still apologizing. She shifted forward to speak to Errol.

“Drive to midtown and back.”

Errol took off his glasses and pinched the bridge of his nose.

“It’s almost three,” I said, but the partition went up and off we went. For ten blocks or so Aimee said nothing at all and neither did I. As we passed through Union Square she turned to me: “Are you happy?”

“What?”

“Answer the question.”

“I don’t understand why I’m being asked the question.”

She licked her thumb and wiped some mascara I had not realized was running down my face.

“We’ve been together, what? Five years?”

“Almost seven.”

“OK. So you should know by now that I don’t want the people who work for me,” she explained slowly, as if talking to an idiot, “to be unhappy working for me. I don’t see the point in that.”

“But I’m not unhappy!”

“Then what are you?”

“Happy!”

She took the cap off her head and pulled it over mine.

“In this life,” she said, falling back against the leather, “you’ve got to know what you want. You have to visualize it, and then you have to pull it down. But we’ve talked about this many times. Many times.”

I nodded and smiled, too drunk to manage much more. I had my face wedged between the walnut and the window and from here I had a fresh view of the city, from the top down. I’d see the roof garden of a penthouse before I saw the few, stray people still out at this hour, splashing through puddled sidewalks, and I kept finding in this perspective uncanny, paranoid alignments. An old Chinese lady, a can collector, in an old-fashioned conical hat, pulling her load — hundreds, perhaps thousands, of cans gathered together in a huge plastic sheet — under the windows of a building I knew to contain a Chinese billionaire, a friend of Aimee’s, with whom she had once discussed opening a chain of hotels.

“And in this city you really need to know what it is you want,” Aimee was saying, “but I don’t think you do know, yet. OK, so you’re smart, we get that. You think what I’m saying doesn’t apply to you, but it does. The brain is connected to the heart and the eye — it’s all visualization, all of it. Want it, see it, take it. No apologies. I don’t apologize ever for what I want! But I see you — and I see that you spend your life apologizing! It’s like you’ve got survivor’s guilt or something! But we’re not in Bendigo any more! You’ve left Bendigo — right? Like Baldwin left Harlem. Like Dylan left… wherever the fuck it was he was from. Sometimes you gotta get out — get the fuck out of Bendigo! Thanks be to Christ we both have. Long ago. Bendigo’s behind us. You get what I’m saying, right?”

I nodded many times over, though I had no idea what she was saying, really, apart from the strong sense I usually had with Aimee that she found her own story universally applicable, and never more so than when drunk, that in these moments we all of us came from Bendigo, and we all of us had fathers who had died when we were young, and we had all visualized our good fortune and pulled it down toward us. The border between Aimee and everybody else became obscure, hard to make out exactly.

I felt sick. I hung my head like a dog into the New York night.

“Look, you’re not going to be doing this for ever,” I heard her say, a little later, as we entered Times Square, driving beneath an eighty-foot Somali model with a two-foot Afro dancing for joy on the side of a building in her perfectly ordinary Gap khakis. “That’s just fucking obvious. So the question becomes: what are you going to do, after this? What are you going to do with your life? ”

I knew the right answer to this was meant to be “run my own” this or that, or something amorphously creative like “write a book” or “open a yoga retreat,” for Aimee thought that in order to do these sorts of things a person only had to walk into, say, a publisher’s office and announce their intent. This had been her own experience. What could she know about the waves of time that simply come at a person, one after the other? What could she know about life as the temporary, always partial, survival of that process? I fixed my eyes on the dancing Somali model.

“I’m fine! I’m happy!”

“Well, I think you’re too much in your own head,” she said, tapping hers. “Maybe you need to get laid more… You know, you never do seem to get laid. I mean: is it my fault? I set you up, don’t I? All the time. You never tell me how it goes.”

Light flooded the car. It came from a huge digital ad for something or other but inside the car it felt delicate and natural, like the break of day. Aimee rubbed her eyes.

“Well, I’ve got projects for you,” she said, “if you want projects. We all know you’re capable of more than you’re doing. At the same time, if you want to jump ship, now would be a good time to do it. I’m serious about this African project — no, don’t roll your eyes at me; we need to iron out details, of course I know that, I’m not a fool — but it’s gonna happen. Judy’s been talking to your mum. I know you don’t want to hear that either, but she has, and your mother is not as full of shit as you seem to think she is. Judy feels that the zone… Well, I’m loaded right now and I can’t remember where it is right now, tiny country… in the west? But she thinks that might be a really interesting direction for us to go in, it’s got potential. Says Judy. And turns out your honorable member of a mother knows a lot about it. Says Judy. Point is, I’m going to need all hands on deck, and people who want to be here,” she said, indicating her own heart. “Not people who are still wondering why they’re here.”

“I want to be there,” I said, looking at the spot, though under the influence of vodka her little breasts doubled themselves, then crossed, then merged.

“I turn now?” asked Errol hopefully, through a microphone.

Aimee sighed: “You turn now. Well,” she said, returning to me, “you’ve been acting screwy for months, since London. It’s a lot of bad energy. It’s the kind of bad energy that really needs to be grounded otherwise it just keeps passing round the circuit, affecting everybody.”

She made a series of hand gestures here that suggested some previously unknown law of physics.

“Something happen in London?”

By the time I’d finished answering her we’d looped back and reached Union Square, where I looked up and saw the number on that huge ticking board speeding forward, billowing smoke out of the Dantean red hole at its center. It gave me a breathless feeling. A lot of things that happened in those months in London had made me breathless: I’d finally given up my flat, for lack of use, and stood at a crowded hustings waiting all night to watch a man in a blue tie ascend the stage and concede victory to my mother in a red dress. I’d seen a flyer for a nostalgic nineties-hip-hop night, at the Jazz Café, and wanted urgently to go, but could not think of a single friend I might take, I’d simply traveled too much the past few years, was not on any of the usual sites, did not keep up with personal e-mail, partly out of lack of time and partly because Aimee frowned on our “socializing” online, fearing loose talk and leaks. Without really noticing it, I’d let my friendships wither on the vine. So I went alone, got drunk and ended up sleeping with one of the doormen, a huge American, from Philadelphia, who claimed to have once played professional basketball. Like most people in his line of work — like Granger — he had been hired for his height and his color, for the threat considered implicit in their combination. Two minutes of smoking a cigarette with him revealed a gentle soul on good terms with the universe, ill-suited to his role. I had a little pouch of coke on me, given to me by Aimee’s chef, and when my doorman’s break came we went to the bathroom stalls and took a lot of it, off a shiny ledge behind the toilets that seemed specifically designed for the purpose. He told me that he hated his job, the aggression, dreaded laying hands on anyone. We left together after his shift, giggling in a taxi as he massaged my feet. When we got back to my flat, in which everything was packed up in boxes, ready for Aimee’s huge storage facility in Marylebone, he got hold of the aspirational pull-up bar that I’d put up above my bedroom door and never used, attempted a pull-up, and ripped the stupid thing from the wall, and part of the plaster, too. In bed, though, I could hardly feel him inside of me — shriveled up by the coke, maybe. He didn’t seem to mind. Cheerfully he fell asleep on top of me like a big bear and then, with equal cheeriness, at around five a.m., wished me well and let himself out. I woke up in the morning with a nosebleed and the very clear sense that my youth, or at least this version of it, was over. Six weeks later, on a Sunday morning, as Judy and Aimee frenetically texted me about the archiving, in Milan, of a portion of Aimee’s stage wardrobe, years 92‒98, I sat, unbeknownst to them both, in the walk-in clinic of the Royal Free Hospital, awaiting the results of an STD and AIDS test, listening to several people, far less lucky than I turned out to be, being taken into side rooms to weep. But I didn’t speak to Aimee of any of this. Instead I was speaking of Tracey. Tracey of all people. The whole history of us, the chronology sliding woozily back and forth in time and vodka, all resentments writ large, pleasures either diminished or destroyed, and the longer I spoke the clearer I saw and understood — as if the truth were a sunken thing rising up through a well of vodka to meet me — that only one thing had happened in London, really: I’d seen Tracey. After so many years of not seeing Tracey I had seen her. None of the rest mattered. It was as if nothing in the period between the last time I saw her and this had happened at all.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Swing Time»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Swing Time» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Swing Time» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.