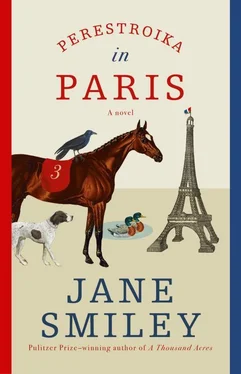

That first morning, he’d watched the horse for a while, and his immediate instinct had been to have her caught and vanned away. But she was a beautiful horse—a rich bay with a long tail, a thick mane, and large, expressive eyes—and the more he looked at her, the more he thought that, at least for now, she gave the Champ a certain style: every landscape needs a figure in it, perhaps especially a figure that is only intermittently visible, that is mysterious and alert. He caught sight of her often, and watched her when he could. He saw from her footprints and her manure that she was jumping out of the fenced area to graze in the evenings. Perhaps the tourists didn’t notice her, or, if they did, thought that because she was inside a fence during the day she was provided by the authorities as a picturesque gesture. Perhaps his employees did notice her, but it was not for them to say anything if he didn’t. So everyone wordlessly shoveled up what she left, as they cleaned up after dogs and cats and birds and foxes and once an ocelot that had escaped from its owner on the Avenue de Suffren, a much more troublesome beast than a horse. Pierre knew he should wonder where the horse came from, and report her, but, for now, he reassured himself that he was not in Animal Control, and if they wanted her, they could come and look for her themselves.

Although Frida didn’t like the mallards because of the smell, and Raoul continued to disdain them as common common common (you saw them everywhere—did Paras realize they would mate with any Anatidae?), Paras considered Nancy good company, and extremely patient. Sid, Nancy said, did not live here all year round. He appeared every autumn about this time, decked out in green. He stayed with her for a while, and then flew south. He was sensitive to the cold. Winter migration was statistically the norm, but if you lived in Paris, well—Nancy cocked her head, then went on—it was an issue between them, but she was a homebody. She liked her territory. The pond had frozen over completely only one time. Down south (she had gone with him once), you had to put up with chaos. The worst of it around here, according to Nancy, was that, in addition to her own six or eight or ten eggs (one year she laid twelve), if she didn’t hide her nest well, other eggs could turn up, and there you were, you had hatched some completely alien little thing before you knew what was what. Her last bunch had just flown off a month before. Nancy pushed them out as soon as they could go—she realized that she was a bit impatient about it, but they were well cared for and strong, and she felt that she needed at least some time on her own, didn’t Paras agree? Paras of course agreed, since she liked to have a lot of time on her own.

In half a year, late in the spring, there would be another migration—only the drakes that time of year. And good to see the back of them. A drake plus ten nestlings was too much. “What were the nestlings’ names?” asked Paras idly.

Nancy shook her wings and cocked her head. She said, “I have no idea. It’s your mate who names you, not your mother.”

“For horses,” said Paras, “it’s humans. Our dams just call us ‘sonny’ or ‘honey.’ But humans don’t seem to know the difference between two horses unless they name them, so we allow it.” She confided in Nancy that, even if a horse didn’t have showy white markings, he or she always had distinctive cowlicks and dapplings and ways of moving. It was a mystery to all the racehorses that they had to wear not only jockeys but brightly colored cloths so that the humans could tell them apart. In even the most crowded race, every horse knew who was who. Some horses found the politics of it all quite nerve-racking, but, as a front-runner, Paras didn’t pay much attention to that.

Sid was a bossy one, but Nancy quacked that she could not complain, and she had never closed herself off to him, as some ducks did, not only to interlopers, but to their own mates. He was a good provider, and a duck had to be fat, because the ducklings would slim her down to nothing if she didn’t take care of herself ahead of laying time. And anyway (Nancy lifted her wings and tossed her head), Sid knew how to shake a tail feather. Quack-quack-quack. Paras found it soothing to walk around the grass, taking bites of this and that and listening to Nancy. Where, she asked, did the drakes go? Nancy had no idea. Of course, they said that they roamed far and wide—to the mountains, to the oceans, etc. But a duck had no way of knowing. Except for that one sojourn to the south, Nancy had lived in the Champ de Mars for years. It was an excellent spot, no matter what certain mallards said about other neighborhoods. There was plenty of cover, plenty of water, plenty of food. The noise didn’t bother her—she hardly heard it anymore.

“It is noisy around here,” said Paras.

Much of the noise was made by Sid, whose high-pitched mode of expression made Paras’s ears flick. Sid was in charge of the nest, and he had decided that this year, since Paras and her friends were always present, they needed to build it in a safer spot. So he marched about the pond and the neighboring groves, trying to make up his mind. “There, you see,” he said, “the outer edge is too far into the open. Very dangerous, but if we make the nest smaller, that has its dangers, too. We haven’t lost a duckling in three years. It’s a point of pride for us, and I speak for Nancy as well as myself, because we each have our duties and responsibilities, and my responsibility is the nest.” Sid stepped carefully, looked here, looked there, kept going. “Can’t be too far from the water,” said Sid. “Very vulnerable if they have to walk far. Owls at twilight, hawks during the day, foxes anytime, dogs for that matter, cats. You ask anyone, mallards are fair game.” He coughed and glanced over his shoulder and shuddered. “Rats.”

“I don’t mind rats,” said Paras. “They clean the place up.”

“They are ruthless. There has never been a rat who let an egg be!” screamed Sid. He walked up the face of a large rock, and plopped down in the sun. Sunny days were few and far between lately, but Paras didn’t much mind the rain. It was easier to live outside in all weathers than it was to be confined to a dark stall, unable to see much, but hearing every little thing, day and night. All the horses complained about being cooped up, even the least curious ones. And then, when the humans took you out, they got spooky when you were startled by something. The better riders just sat there, and said, “Ah-ah,” but a sensitive filly like Paras could feel in her very bones that their hearts were pounding. If you lived out, there wasn’t much that surprised you. Paras could see things all over the Champ de Mars—humans large and small, dogs large and small, birds of all kinds soaring and swooping. If you lived out, every noise had a reason, every sight a before and an after. No surprises. Pretty soon, Nancy joined Sid on the rock, and both of them seemed to go to sleep.

Paras stretched, shuddered all over, and stepped out into the open space. In the last few days of rain, there hadn’t been many humans around; the sunshine would bring them out, so Paras thought she should go for a little trot before they showed up. She jumped the fence and headed down the allée, head up, ears up, pace brisk. It felt good. She flicked her tail and rose into a canter. The footing was firm, wet but not at all slippery. She enjoyed the sound of her own hoofbeats. She had been bred to race thirty-two hundred meters; a good gallop gave her the opportunity to blow out her lungs and get some exercise. At the big building at the far end of the Champ, she came down to an easy walk, turned around, and trotted back, pausing here and there to take some bites of grass. The few humans running not far from her either didn’t notice her, or pretended not to notice her, but their dogs kept barking: “Who are you! What are you doing here! I never saw you before! You don’t belong here!” Paras ignored them, and if a human looked her way, she lifted her head and trotted all the more proudly. Frida said that there was a way to conduct yourself “as if” you had your own human about. You were calm and proud and never threatening, because you didn’t want to scare anyone. You kept your distance—humans did not like strange animals to come too close to them—and you did not ever look at them unless they were looking at you. In that case, you could give them a friendly glance—I would like to know you if I had the time, but I am busy at the moment. The other important thing was to be as clean as you could be, and so Paras tried to roll in wet grass as often as she could, and to stay out of the mud. Paras was a well-bred horse, so she liked to be clean, anyway.

Читать дальше