It was the sight of a plastic bag filling up with a puff of air and lifting itself out of a garbage bin that reminded Frida of what Jacques had taught her about money. When it drifted to the ground and skidded off, she ran after it, secured it with her paw, and took it between her teeth. Here she had spent the entire summer scuttling about, pretending to be owned by someone, and losing lots of weight, when what she really had to do was perform a few tricks. Humans were pushovers for tricks. They always laughed and gave you a treat. How many times on the street with Jacques had she rolled over, or covered her eye with her paw, or put the toy in the guitar case, or balanced the piece of bread on her nose and then tossed it and caught it? Jacques, of course, did tricks, too—playing songs and sometimes singing. Tricks got you money, and then you took the money and exchanged it for what you wanted. The thing she must do was put some of the money into the plastic bag, then carry the bag to the meat market.

It could not be said that the bag was easy to manage in the breeze rising off the river, but she did uncover the purse, nose it open, and take a bill in her mouth. She then scratched at the bag with her paws, and, when the edges came apart, pushed the bill between them. She picked the whole unwieldy object up in her mouth, then kicked the loose dirt back over the purse. She looked around. The only humans she could see were running ones, rushing away through the trees. Running humans never looked at a thing, Frida thought. Perhaps they could not do two things at once, which was why she had never seen even the fastest ones catch a pigeon.

But the meat market was not open. The succulent offerings in the windows were dark; the lights were off. Even the fragrance had dimmed, though it was quite rich and varied just at the base of the door. Frida felt her haunches sag in disappointment. And then she saw that the proprietor of the vegetable shop was standing in his doorway, his hands underneath his apron. He smiled and said, “Mademoiselle!”

There was a table just inside the door. Frida trotted over to the proprietor (she felt that the trot was a dog’s most self-possessed and dignified gait), stood up on her hind legs, put her paws on the table, and spit the bag onto its surface. The man looked at her, then picked it up and saw the note inside. He laughed. There would be no chicken, Frida thought, but there would be a roll, and maybe cheese. She went farther into the shop. She stood on her hind legs and looked into every bin. The man, Frida thought, was actually rather intelligent. If she paused at the bin, he put something from that bin into the bag. As a dog of the streets, she had eaten plenty of vegetables, and though it was true that she had no use for a raw potato (fried potatoes were quite a different matter), she didn’t mind green beans or carrots or even a leaf or two of romaine. And her bill didn’t go very far—a bread roll, beans, carrots, romaine, another bread roll. The man took her bill politely, smoothed the handles of the bag into a circle, and held them out. Frida opened her mouth, and he gave her the bag. Then she left the shop, heading briskly down the street as if her master were waiting for her. She could hear the man laughing as she ran.

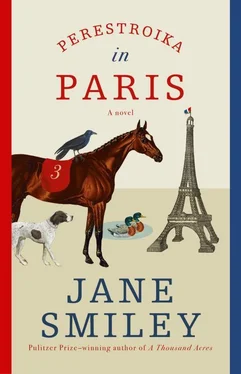

Paras was still lying down when Frida returned, but she was awake. Raoul was perched on her rump. He had just finished telling her what he knew about the word “perestroika,” which wasn’t much, something about either always making plans or letting things turn out as they would and making the best of that. (“If that wasn’t horseracing,” Paras thought, “then what was?”) Now he was telling her about an argument he was having with another raven, who claimed the head of Benjamin Franklin, which was immediately below Raoul’s nest. “Everyone knows that a raven’s territory is spherical,” said Raoul. “It is widest around the nest, and then diminishes outward. I have almost no claim to the hillside below my nest, but the head of the statue is well within my territory, and I could make a case for the lap, too—”

Frida dropped the bag in front of Paras, and it fell open. Paras nosed out a carrot, bit it in two, and munched it down. She said, “How delicious! I’d almost given up hope. You’d think they’d plant a few of these in such a large park, but I haven’t found them.”

“I bought it,” said Frida.

“Ah, commerce! A concept, I must say, that we Aves have given the world.” Raoul flapped his wings, but it was only a flourish of self-congratulation. He didn’t fly away; rather, he sidestepped over to the bag and helped himself to a green bean. This drew the attention of Sid and Nancy, who walked out of the pond and stared. Paras took another carrot and bit it in two. Frida ate the second half, then one of the small rolls. It was fresh and delicious. “No apples?” said Paras.

“I don’t quite know what an apple is,” said Frida.

“Malus domestica,” cawed Raoul. “A waxwing will eat an apple.” He coughed as if this was an unusual affectation. “I have tasted apples.”

Sid and Nancy waddled closer, then sat down. No screaming or quacking. Frida took the second-to-last piece of bread out of the bag, carried it over to them, and dropped it. Jacques had never minded sharing his food with others. Sid ate part of the bread; then Nancy ate the rest. Sid said, “We’ve eaten apples. A child tossed us some bits just a few days ago. They’re all right.”

“I love them,” said Paras.

Frida knew this was a hint.

The next day, Frida supplied herself with another bill and went to the market earlier in the day, just when every shop on the street was opening. She of course went to the meat market first—she could hardly help herself, the fragrance was so enchanting—but the woman who kept the shop was sweeping the step. She waved her broom at Frida and said, “Ahh, shoo, shoo! Get!”

Frida backed away and sat down, still staring at some pale, fat, featherless carcasses in the window.

She felt a pat on the head; the man said, “Ah, dear girl, you have returned again! The chicken is indeed very lovely.”

Frida had found with Jacques that if she was still and steady and opened her eyes very wide, he was more likely to do as she wished, and, indeed, the man held out his hand, took her bag, and removed the bill from it. Then he went into the meat market. She stepped carefully up to the window and touched it with her nose beside a pile of meaty bones, and he put two of these in the bag, paid for them, and came out. He did not give her the bag, though. Instead, he carried it to his own shop. Frida followed him. When she was across the threshold, he took two coins from the register and said, “Mademoiselle, I owe you two euros from your previous visit.” Frida indicated that she would take something from each of the bins closest to the street. When she had spent all of her money, the bag was heavy in her jaws, and she knew she would have to set it down more than once on her way back to the Champ de Mars. But the bones motivated her.

The bag broke as soon as she set off.

The man clucked, clapped his hands, and said, “Oh dear!” And then he gave her another bag, this one sturdy.

Between them, Raoul, Paras, and Nancy identified the fruits—orange, apple, pear, another apple, lemon, banana. Paras took the two apples; Raoul had seen lemons but never tried one; and Nancy took the orange. No one knew what to do with the banana, so they left it beside the pond. Frida carried the bones to her hollowed-out retreat and gnawed them happily.

THERE WAS a human who knew that a horse lurked about the Champ de Mars. He had seen her the first morning, inside the fence around the North Pond, when she stretched and snorted and hoisted herself to her feet, then made her way to a bit of grass half hidden by some bushes. His name was Pierre, and he was the head gardener of the Champ de Mars. Pierre loved the Champ de Mars, thought it was the oddest spot in Paris—out west, right along the Seine, flat enough to have begun as a hundred-hectare training ground for the students in the École Militaire, then large enough to host horse racing (before that moved to Longchamp), then to host what was now called a world’s fair, not to mention the Tour. It was full of grass and trees and gardens and cars and ponds and trash (Pierre did the best he could with that), over a kilometer long and half a kilometer wide, peaceful sometimes, busy other times, especially in the summer, but not so much now, in the late fall.

Читать дальше