Inside, the man behind the counter said, “Orlande! Close the door. What a wind! I don’t know why we are even open this evening.”

Orlande stood up, backed up, and then bowed, clearly inviting Frida into the pâtisserie. Frida was undecided—the interior of the restaurant was warm and light, and smelled good. There was no one there except the two men, but, still, it was inside. And at that very moment, Raoul flew up behind her and pecked her very smartly just above her tail. She jumped, Orlande laughed, and she stepped into the restaurant. She immediately sat down in her most dignified manner and offered Orlande her paw. He took it, shook it. From behind the counter, the other man tossed something. Orlande put his hand up and caught it, then showed it to Frida. It smelled good—it was a small warm roll. Frida took it politely, dropped it on the floor, ate it in as dignified a manner as she could. After she had done so, she dipped her head. Orlande patted her again.

“Beautiful dog,” said the man behind the counter. “I’ve seen her around here before. I think she might belong to a family who has an apartment down the Avenue d’Eylau, but I thought they went to Cannes for the winter. I can’t imagine that they would leave her here.”

“Who would do such a thing?” said the first man. “André, she has a terrifically expressive face.”

André set a bowl on the top of the counter. Frida could see steam rising off it. It was very fragrant. Beside it, he set a croissant, something she had shared with Jacques several times. He blew on the bowl. In the meantime, although there wasn’t very much space, Frida did a few of her tricks—she put her paw over her eye, she lay down, curled up, and rolled over, she offered Orlande her other paw. After these, as if reading her mind, he took some bread that he had torn out of a loaf and set it on her nose. She paused a moment, then flipped her nose, tossed the bread, and caught it. Both men laughed, and the first man applauded. Then he brought the bowl to her—it was full of chicken broth—and the croissant. She ate carefully, trying not to make a mess. The croissant was delicious.

The view from inside the shop was most definitely different from the view outside—the windows were dark, and Frida herself was reflected in them; there was no surveying the landscape or seeing who might be coming. What with the talking of the two men, the banging of pots and pans, and the scraping noise when her new friend moved a table or a chair, she couldn’t hear much, either, and as for her most important and discerning sense, she felt rather as if she were being drowned in rich odors. Outside, there were plenty of smells—the damp in the air, the leaves, the trees, the birds and animals, the sharper scents of cars and trucks going by, the differing scents of humans (young boys—quite strong; women—almost nothing except occasionally the scent of a flower)—but they drifted past one or two at a time, always from a specific direction, easy to interpret, especially by a cautious dog such as herself. Being inside made her a little afraid to go back outside. It was, indeed, very very dark out there.

Orlande set a dish of water on the floor, and Frida drank it. She was quite full, and warm, too.

The door opened again, and four humans, two elegant young men and two young women in high heels, came in, laughing. André straightened up and began rearranging his offerings, and Orlande smiled, showed the four humans a table. They stepped around Frida without seeming to notice her. The next time the door opened, and another pair of humans entered, Frida slipped out as the door closed behind her.

From the railing of the Métro staircase, Raoul called out, “Good thing you don’t have a long tail.”

“I’ve often thought that,” said Frida. She walked away from the Pâtisserie Carette toward the entrance to the museum, which was dark and no doubt chilly, but faced away from the wind. Raoul wanted to say, “The word among the Aves is that this unpleasant accumulation of frozen precipitation will be gone by the end of the day tomorrow. I gather from passing flocks of Bombycilla garrulus —some may call them waxwings—that warm weather is on its way.” But, conscious of his recent moment of self-knowledge, all he said was “It’ll warm up.”

Frida estimated that she might be able to curl up in the corner of the entrance to the museum, entirely out of the way, and protected, maybe, from guards and the gendarmerie for most of the night. As she lay down on the hard surface, Raoul landed and walked back and forth, continuing to chat. “You know, by the way, that Nancy has laid six eggs.” He wanted to say, “There could be more to come—mallards are a profligate bunch—but she seems to think she is finished. She seems content to be on her own, I must say. I might not have told you that I have a mate myself, and numerous offspring.” He thought of Imelda, her “very large and important family down around Vincennes.” Had Frida ever been to Vincennes? The question almost popped out. In Raoul’s opinion, the Corvus of Vincennes were only exceeded in their sense of self-importance by the Corvus of Tours. But he was coming to understand that all importance is really merely self-importance. Though the thoughts unrolled in his head, he pressed his beak shut. He said nothing more, and so Frida drifted off to sleep—full, indeed, and surprisingly warm.

NOT LONG AFTER THAT, Paras was lying in the grand salon in the dark, enjoying the stillness as well as her own full belly (Étienne had spent the late afternoon soaking a bag of split peas for her evening meal, which he served with shredded cabbage). The house was so quiet that Paras could swivel her ears and hear all sorts of things—the sound of cars skidding along the Avenue de la Bourdonnais, the ruffling snores of Madame de Mornay behind the door of her room, even, perhaps, the sound of Étienne in his room, turning the pages of his book. Paras had long, slender, mobile ears. She had always had good hearing—part of her skittishness. She could hear the rumbles of her own belly, which she knew was a good thing. Étienne had decided, at least for the time being, to rearrange the furniture of the grand salon so that, if Paras was lying down beside the back wall, a blind, deaf, ailing old woman might not be able to sense her there. Paras didn’t mind—it was rather like having a stall with a very high ceiling and very low walls.

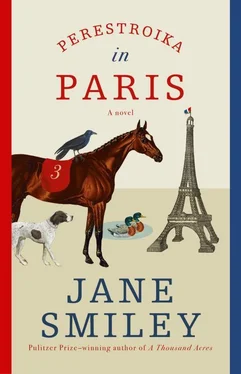

Paras was replaying in her mind her last race, her second win, over the hurdles at Auteuil. There had been not so many horses in the race. Her previous win, also at Auteuil, had been rather like a stampede, a rush over the hurdles that had made her so nervous that she simply had to get out in front of everyone and run away. The jumping part was the least of it. Hearing the pounding of hooves and the snorting and roaring of horses breathing behind her like a great wind had driven her forward so energetically that she had not really wanted to stop even after the last jump and the finish line, with the jockey sitting up and turning her. She hadn’t quite understood at that point what a “win” was. But when they did trot back to Delphine and Rania and Madeleine, and when the jockey gave her three exuberant slaps on the shoulder, and when she saw that all the other horses (in particular the gray filly who had come as far as her hip and faded back) looked glum and exhausted, while she felt pleased and full of energy, she saw what winning was and knew that it was good. That had been in warm weather, the course fragrant and green. Her recent win at Auteuil was a more modest and autumnal affair, late in the day, not many spectators, but she had galloped with pleasure, jumped with ease, and stayed two lengths ahead of the chestnut behind her. She was again a front-runner, but out of curiosity rather than fear—it was strange and enjoyable, the way one hurdle seemed to lead to another, not frightening, but only a great big stride and then onward to the next one. She knew that when she was older Delphine would put her in jump races, where the obstacles would be bigger and more solid than “hurdles” (she had heard her say that to Rania). Paras had looked forward to that, so why had she walked (well, trotted) away from it all? Curiosity was the only answer. Or, as she thought now, sheer ignorance. Paras blew some air out of her nose and stretched out flat on her side. At once, she heard another scratching sound, this one inside the wall, and then there was a rat—dark gray, almost black, fat, but rather small, its whiskers twitching—right in front of her nose. She snorted at the odor, and the rat stepped aside but did not run away. He said, “Welcome.”

Читать дальше