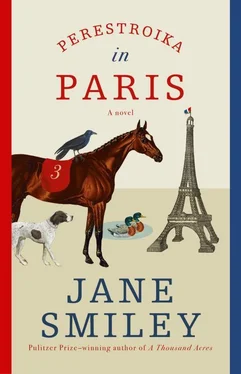

As she trotted over the bridge, she was well aware of the enormous lit Tour over her shoulder, but she didn’t turn to glance at it. She felt that she was somehow escaping its chilly aura. Once, she had asked Paras what she thought of the huge thing, and Paras had said, with bona-fide curiosity, “What difference does it make to me?,” and Frida hadn’t been able to answer that question. Raoul and other birds seemed to view it as a sort of tree/building hybrid, and he had told Frida that various flocks over the years had attempted to colonize it, not pausing to wonder, as he said, “why no flocks had dared come before them—but every bird thinks of himself as an adventurer.” Of course, he also remarked, the humans were not going to allow any flocks of Aves a free hand with that tower, not even Corvus corax in all of their many noble variations.

Once across the bridge, which was clear of snow but icy, Frida took a chance and did a thing she could not have done with Paras in tow, which was to go straight up the hill, beside the pool and then between the two buildings, as if someone were calling her and she had a right to be there.

And, indeed, the cafés around the square were ablaze with light, open for customers even if the night was chilly and slippery. Much of the snow had melted off during the day, or been swept to one side. The streets were shiny, and a few cars and taxis were making their cautious way here and there. Frida went over and sat beside the door of the Pâtisserie Carette, arranging herself so that she was facing outward toward the square, but also half looking in the window. She took a deep breath or two and waited.

With the wind blowing in her face, Frida suddenly felt cold for the first time—all day long, she had been on the move, up the Avenue de Suffren, then back and forth across the Champ de Mars, then pacing in front of the house that her new horse friend had disappeared into. She had been distracted from the chill, first by the boy and then by events. At any rate, Frida was such a big, strong, muscular dog that she didn’t feel the cold the way some dogs did. Her coat was short but dense, well suited for racing into rivers and lakes after ducks or into fields after pheasants, partridges, and other birds. No body of water that she had ever seen had intimidated her, including the Seine itself, which was plenty warm, even in the winter—at least, Frida thought so. But now, in the semidarkness, with the brilliant lights of the pâtisserie shining in her eyes, and the sight of the waiters relaxing, smoking, chatting among themselves as they wondered whether any customers would come in, she began to shiver. Was it fear or dread or cold? Frida herself didn’t know. And the sky above was so dark that Frida could see nothing except the wavering lights of the giant tower across the river.

A voice said, “What in the world are you talking about?”

It was the voice of Raoul. Frida peered into the darkness. He was perched on the railing of the Métro entrance. Every so often, Frida had taken refuge in the Métro, but it was dangerous and loud, and the weather had to be very very rainy for her to choose the Métro. Frida sneezed, then said, “Hello, I was wondering where you had gotten to.”

“I went to my nest, of course. A Corvus of my station has more things to attend to than one horse. But what in the world are you talking about?”

“What do you mean?” said Frida.

“Surely, you realize that you are always mumbling on about something?”

“No,” said Frida. “I didn’t realize that.”

“My heavens,” said Raoul, “I’ve been watching you since the summer. I’ve never seen such a talker. Mumble-mumble this, mumble-mumble that. I thought that that was the way Canis familiaris remembered things, by talking about them all the time.”

Frida felt her shivering intensify. No one had ever said this to her, but she knew instantly that it was true. She hardly ever barked—Jacques had taught her that her bark was excessively loud and therefore dangerous if a dog (and a man) wanted to be left alone. And Jacques had not liked whining, and yet there were so many feelings and ideas that required expression of some sort. Even so, she said, “I don’t really know what you mean,” and Raoul commenced to grumble and chat in a very doglike voice that Frida recognized perfectly as the voice of sometimes her only friend, herself. She sighed. Then she said, “That’s a good imitation.”

“Most Aves are adept at that,” said Raoul. “You know about Psittaciformes, of course. They are an invasive order, but humans like them for their color, I suppose—humans are very shallow in some ways. Corvus are just as adept at different dialects as Psittaciformes, but we get far less credit—”

“What is a Psittaciform?” said Frida.

“A parrot, in common parlance, but of course there are many species. There have to be, because so many earthly beings are reincarnated as Aves. It’s very educational for them. Or us, I might say. I feel that, in my former life, I was a government official; perhaps I was not as effective as I should have been. And look at Sid and Nancy. Terribly anxious, even for common mallards. My guess is that in a former life they were impulsive and careless….”

Frida lay down, put her head on her crossed paws, and closed her eyes. There was a silence, and then Raoul said, “I do tend to go on, I know. It is a feature of age. I have learned so many things in my life that they just force their way out of my beak.” Then he said, “I did peek in the windows at the Rue Marinoni today. The first time, it looked as though our friend was having a lovely nap, all stretched out on the floor, and the second time, she was eating from a very large bin. The boy seems to like her.”

“No good can come of this,” said Frida.

“Difficult to judge that,” said Raoul. “The boy seems to do well on his own, for a boy. My view is that the danger is not to the Equus, it is to the boy. Over the years, I have observed that adult humans are very nervous if an immature human seems to be without a protector.”

Frida’s ears flicked at that word, “protector.” With dogs, she knew, the question of who was the protected and who was the protector was always an open one. When you saw, on the streets of Paris, a human and a dog walking along, it could be either one, no matter how very small the dog was. She had seen dogs who might not even come up to her knees on the alert, not only looking this way and that, but barking, “Stay away, stay away! I will kill you if you hurt my human!” And it was true that, if there were three dogs together, it was the job of the smallest dog to keep an eye out and alert the larger dogs if danger was at hand. Had she been Jacques’s protector? If so, perhaps she had not done a very good job.

Raoul said, “Pardon me, but there you go again. Talking to yourself. Is there something that you would like to communicate?”

Frida forced herself to remain silent for a very long moment, then said, “I suppose that communicating is rather dangerous.”

Raoul said, “I hadn’t thought of that. For Aves, not communicating is very dangerous. You never know when some hawk or owl might take silence the wrong way.” And then he said, “Indeed. I will shut my trap now. Good practice.” He flew upward, and the door beside Frida eased open.

The man who opened the door was not old, and he had a scowl on his face—Frida knew he intended to chase her away, perhaps to kick her—she had seen that in her day. But she felt too sad even to stand up. Let him kick me, she thought. She turned her head and stared at him. He stared back at her, and his face softened. After a moment, he squatted down and patted her on the top of her head. He said, “I have never seen such a sad face on such a beautiful dog.” He stroked her several times, kindly and smoothly, as if he knew just how.

Читать дальше