“Excellent!” he said. “First quality! Provenance, the Costa Brava, or even North Africa. Very firm, and yet chewy, almost pulpy.”

“What are you eating?” said Paras.

“Tenebrio molitor!” said Raoul, his mouth full. “Mealworms!”

“I ate one of those, once,” said Paras. “It was in the oats.” She wrinkled her nose in the air again.

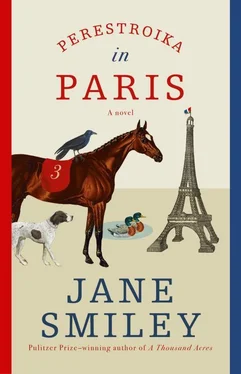

Raoul hopped over onto the boy’s wrist. The boy’s arm dipped, but he managed to lift it, and Raoul perched there, picking the mealworms out of his hand one by one, then gulping them down. They did look rather large. When he was finished, he dipped his head in thanks, and hopped back onto Paras’s haunches. The boy turned, picked up his bag, and continued across the Champ de Mars. Paras followed him. Behind her, Frida started barking her deep, startling bark. Raoul said, “Ignore her. As I said to her, her life with that fellow, no matter how well intentioned he was, and, yes, I admit it, affectionate for a human, and he did not abandon her—I had to explain to her what death is—”

“What is death?” said Paras.

Raoul said, “I keep forgetting how young you mammals are. But, to finish my thought, he had his own issues, and if indeed he preferred to live out in the open rather than to take shelter, especially in the winter, well, look where that ended up, and, yes, I know he—as we Aves say—‘flew upward’ in the summer, but damage accumulates in every species—”

“What’s the problem?” said Paras. Frida was still barking.

“She thinks you are being captured and put in jail.”

Paras stopped walking. She said, “She has mentioned that. But what is jail?”

“Oh, goodness, you know, a small enclosed space where you can’t get in and out of your own accord, but must always bow and scrape and do tricks in order to achieve some sort of self-realization.”

“A stall,” said Paras. She turned her head to look at Raoul.

“Something like that,” said Raoul.

“On a day like today, there’s much to be said for a stall.”

“Have you ever been inside a house?”

“Where humans live?”

“Yes.”

Paras, now walking along behind the boy, who was carrying his bag and moving at a decent clip for such a small human, said, “I knew a human who lived in our barn. Her horse lived in one stall, she lived in one stall, and her dog lived in the stall between them. Delphine made her move, though.” She thought again. “Sometimes humans live above us. We can hear them walking around.”

“You have enjoyed a very circumscribed life,” said Raoul. “In my view—and, I would guess, the view of most Aves, especially Corvus —there is nothing quite as amusing as observing humans in their own habitats. They sleep on their backs with their mouths wide open, you know, and there is not much of this walking about that you see out of doors, looking lordly and in charge. It’s all lolling and lazing and stoking themselves with food and drink. Gatherings are different. Quite often they flock together in large, bright rooms, and then they plume themselves and establish rankings. I would like to see a healthy flock of Aves fly into the room and perch on their heads. But, by themselves, they are something of a mess.”

All of this time, Paras had been following about two paces behind the boy, and he’d been glancing at her. They’d crossed the Champ de Mars at an angle, taking the same route Frida always did when she headed for the shops. Frida had stopped barking, and was slouching along in the rear. Every so often, she uttered a sad whine, as if she had given up on them and was talking to herself. The boy now paused. Paras stepped up to him, and he offered her another item from the bag, a piece of bread. She could taste oats in it. It was delicious. Raoul landed in front of the boy and lifted and lowered his head. The boy seemed to understand. He opened the bag and held it for Raoul to look into.

“I thought I smelled cacahuètes, ” said Raoul.

“What are cacahuètes ?” said Paras.

“Your diet is sadly limited,” said Raoul. But he did not explain what cacahuètes were.

They had come to a building, much taller than a stable. A fence covered with impenetrable wintry vines surrounded it. Paras reached out and tasted the dead leaves. Plenty of snow, and the merest hint of a bitter, summer flavor. She spat the fragments out. Frida barked one time, but then sat and stared at them, her ears flat against her head. The boy opened the gate all the way, as wide as it would go. Paras stepped around it, and peered into the yard.

There was not much to see. The snow was not flat—it had mounded against the walls of the building and piled on the windowsills. The sun shone on the snow and the walls and made Paras blink, it was so bright. She snorted and tossed her head. The yard wasn’t as tight as it looked from the outside—spacious enough to walk about in, though not to trot, private in spite of the brilliant sunshine—no branches to scratch her back as she got in and out. Open to clouds and rain and mist and breezes. But right now—not very appealing. Paras made no move through the gate.

Now the boy did something to the black door across from the gate, and then he opened that, too. It was much narrower than the gate, and a horse, or a dog, or a boy, had to climb a step to approach it. He opened it wide. Paras could not see inside—the sunlight on the snow had blinded her a bit—but she could feel warmth billowing out of the doorway like a fragrance, and so, even though Frida barked two sharp barks, and because she was a curious filly, Paras went up the step and through the door (without banging either of her hip bones on the door frame), and Raoul flew in after her. The boy closed the door behind her, and also the gate, and it was a good thing he did, because there was a gendarme on the sidewalk, across the Avenue de la Bourdonnais, who could not believe his eyes. He thought he saw a horse go into a house that he passed every day, a house that he knew was very respectable and had been in the same family for at least a hundred years, but by the time he got there, the gate was closed and locked again. There were no hoofprints visible in the packed snow on the street or the sidewalk, and so he decided that he had, indeed, had too much wine the evening before, on the occasion of his daughter’s engagement party, and that he had better avoid all alcoholic drinks for a few weeks at least. He did see Frida—he stepped toward her in what he considered a friendly manner (she was a beautiful dog; surely, she belonged to someone) and what she considered a threatening manner—he was wearing a uniform, after all. As his hand reached toward her, she backed away (without growling—a good dog never growled at a gendarme), then headed into the Champ de Mars, but away from, not toward, Nancy’s nest and her own den. She made believe she could hear Jacques calling her. The gendarme watched her for a moment, then turned around and went back to his rounds. He proceeded down the Avenue de la Bourdonnais toward the Avenue Rapp, and so he did not see Étienne emerge from the house, lock the gate behind himself, and run as fast as he could, back toward the church.

Every time she went to Mass, Madame de Mornay refused out of hand any sort of automobile ride home. She had her cane, and she had her boy. She allowed the curé to take her elbow and help her down the five stairs out of the church—that was a courteous thing to do, and even when she was a young woman, long long ago, she had allowed her husband to do the same. But then she waved her hand in a gesture meant to indicate that she had no need of him any longer, and she would see him another time, and even though he was worried about the snow (true, the streets were clear by now), he stood silently, with his hands folded, watching her and the boy, who was carrying a small shovel, make their way step by step by step. His predecessor, long retired, had considered her old in his day, and the curé himself was no longer a young man. Every time he saw her, he wondered if there were things he should do to help her and, perhaps, the boy. But he never did anything—he only saw them every so often, and had too much else to think about. He also knew that she would resent whatever he might attempt.

Читать дальше