Frida sighed.

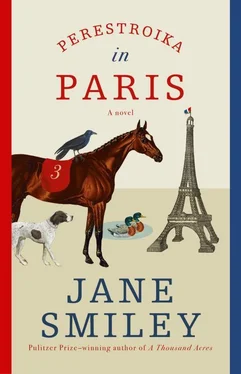

Paras suspected that she was thinking sad thoughts—she had come to understand that many of Frida’s thoughts were sad, that there had been that human who had mysteriously disappeared, that without a human a dog was a little ill-at-ease in a way that a horse was not. Dogs, evidently, saw humans as friends, whereas horses saw them as co-workers. “Well,” said Paras, with her newfound sense that everything would work out, “at the moment, I’m tired and full, so I’ll sleep, and then we’ll see.”

“What are you full of?” said Frida.

Paras pretended not to hear. For now, she wanted to keep Anaïs to herself; anyway, she didn’t think Frida would care for oats.

After Paras curled up and went to sleep, Frida lay still for a long time, trying to keep her feet warm and her nose curled under her knee, but more than once, she could not resist looking at those hoofprints. Finally, she rose to her feet and slinked away, looking back once to see if Paras had awakened, but no—not even her ears flicked. Frida knew from her recent experience that a horse didn’t sleep as much as a dog did, but she was asleep now. Frida took off at a run.

Frida could follow the hoofprints perfectly well—not only by sight, but also by smell, and the fact of the matter was that even a human would notice that Paras had defecated on the dirt road to the north of the pond. What surprised her was that the hoofprints went to the other side of the Champ de Mars, away, from Jérôme’s shop, toward the Avenue de Suffren, a street Frida had explored several times and had never found of the least interest. She might have enjoyed exploring the soccer field, but the fence was too high, and she might have visited one of the dogs she heard barking in the area, but all of them seemed to be safely locked in upstairs rooms. She had visited one vegetable shop, but the man there stayed inside, unlike Jérôme, and none of the customers had noticed her. Nevertheless, the hoofprints stopped at this shop. As far as Frida could tell, everything all up and down this block was closed up tight. She sniffed all the doorsills, growled at a couple of cats but asked no questions, and looked at the hoofprints again. Next to the vegetable shop was a bakery. Frida paused, put her forefeet on the windowsill. The light was dim, and she could see nothing. The glass was cold, with frost creeping upward in tendrils; she could smell nothing. In frustration, she gave a little whine. The door opened, and someone wrapped in white exclaimed, “Out! Out! Get away, bad dog!” Frida backed up into the dark street, and ran off. It was snowing harder now—Paras’s hoofprints had nearly disappeared. When she got back to the abutment, Paras hadn’t moved, and Nancy was so soundly asleep that she didn’t even flinch when Frida touched her with her nose. Nancy, she thought, was a fool—a dog was a dog, and a mallard was a mallard. Frida might exert all of her willpower but still be overcome by instinct, especially if Nancy were to move, but Nancy remained as still as a rock—her feathers, fluffed, were chilled, too. And so instinct did not kick in. Frida lay down in her spot and thought happily about carrying her bag to her usual shops early in the morning, when Jérôme was just taking in supplies and organizing them. He might give her something ugly—something that humans would not like, but that was fine with a dog. He’d done that before. She fell asleep and dreamed of a nice knucklebone.

Paras woke up first, and she did not understand where she was. Something was hanging over her. Something else was all around her. The only warm spot was right beneath her chest. She shook her head and blew out her nostrils, and the air that came out was a white fog. Then she shook herself, and with that, the whiteness encompassing her splintered and fell in little pillows to the ground. She realized that it was snow, that the branches that normally arced above her as she slept had been weighted down with it. They now trembled and lifted, and she could see the world. Not that there was much to see—the earth was white, the trees were white, the pond was white, the sky was white, and the air, too, was still white with flakes drifting downward in the stillness. She turned her head. Snow was mounded against her side almost to her withers. She made her skin shiver; the snow shivered, too, and slipped off.

It was only then that she began to feel cold, and to feel cold meant, as always for a horse, that she had to move. She stretched her foreleg and started to stand up, but Frida was there instantly, saying, “Be careful! Be careful!” She dropped two carrots in front of Paras’s nose. How disappointing‚ they were tasteless, floppy carrots—but she ate them. Frida pressed closer. She said, “The snow is higher than my chest. I had to bound over to the market. It took me forever and was exhausting. I could hardly bring anything back. The streets are not much better than the Champ. No cars anywhere.”

Thanks to Anaïs, Paras had had that full feed—oats, honey, beets, but also bran—almost more than she could eat, though she had eaten every morsel. She was not hungry—but she did expect to be hungry. For the first time in many days, she began to feel a little nervous.

She hoisted herself to her feet.

Thoroughbreds are nervous horses—you heard that all the time, and it was a compliment. It meant that they were quick and smart and attentive. There were non-Thoroughbreds up where she had trained and mostly lived, in Maisons-Laffitte, and all the Thoroughbreds congratulated themselves on not being as dull as those others, with that odd hair around their fetlocks, and those heavy heads and thick coats. You might not be a winner (and every Thoroughbred was well aware of who won, who placed, and who showed), but at least you were a Thoroughbred, and that counted for something. But to be nervous meant to run here and there, and it was pretty clear, even if Frida had said nothing about it, that running about was not a good choice right now.

UP IN MAISONS-LAFFITTE, Delphine was also looking at the snow, and there was more of it than there was down in the city. She had just finished shoveling the walk that led from her small house to the road. Soon she would get on the little tractor she kept for barn work and push the snow away from the horses’ stall doors, out into the middle of the yard. And at some point, the men who took care of the entire training facility would plow the roads. The horses would keep their blankets on today, and she and Rania would take them out into the yard and walk them for an hour around the pile of snow. She had ten horses; all this would take most of her day.

She didn’t have to worry about them for the moment—the night before, she had given them each an extra hay net to get them through the morning as well as the night.

None of her stalls were empty; she still wondered and worried about Perestroika, but another horse had come to take her place, to be trained for the spring season. There was a stall nearby that she used for storage—if Paras turned up, she could put her there. But she had lost hope. No one said it, but everyone thought it—Paras was surely dead. Perhaps she had wandered from Auteuil to the Bois de Boulogne and died there, and her carcass, stripped by vultures and foxes, was hidden in a ravine somewhere. Perhaps she had been kidnapped. A stolen horse might be doing something somewhere. Paras’s markings were not unusual—a plain white star, two little cowlicks in typical spots, otherwise, a red bay, no white stockings. Delphine would recognize her, but to the average person she would look like a multitude of other horses. Delphine had scrutinized horses at all the racetracks she’d been to—in Deauville, down south, in Chantilly—for that telltale luxuriant forelock, those intelligent eyes, those wide nostrils, but she had seen no horse that looked like Paras. She had contacted the racing authorities at France Galop, she had put up signs, she had advertised in newspapers and on Internet forums, she had told all of her friends more than once, she had called all the stud farms in France, England, and Ireland, just in case a mystery mare might show up to be bred, though how a thief might pull that off, she had no idea. But someone else might—a fellow trainer named Louis Paul (and everyone knew that wasn’t his real name) was said to have stolen horses in the past. And he didn’t like women trainers, said they were ignoramuses and deserved no support. Once in a while, he went out of his way to mock her if she didn’t do well in a race. There were plenty of stories about ringers in the racing world—horses disguised to look like other horses so that they could run in a race they might win. She had notified Animal Control. Of course, a stolen horse could be sent to the slaughterhouse, but for what? A handful of euros? And surely any slaughterhouse would recognize that Paras was sound, well fed, young. Delphine had contacts at a few slaughterhouses, too. It was a mystery, as if the horse had vaporized into space.

Читать дальше