When she peers out of the kitchen window she thinks she can see him: a dot by the chain-link fence.

Half an hour later he is gone.

* * *

‘You have been sitting in the sun,’ says Zoya, scrutinising Rachel across the little table in the café along Lesi Ukrainky where they meet. ‘You should wear a hat, like Ivan. You will have brown spots. Skin cancer.’

Rachel rubs her nose and fishes the camomile teabag out of her waxed paper cup. Ivan is sitting on her lap testing his teeth on the cap of the plastic bottle of mineral water he is clutching. She called Zoya to see her one last time on her own – to say goodbye – but as always there is so much that remains unspoken.

‘I like your sunglasses,’ she says. ‘Very Marilyn Monroe.’

Zoya, poker-faced, touches the shades perched on top of her head. ‘So, will you stay with Lucas, or divorce? I think you will divorce.’

‘Zoya!’ Rachel tries to sound outraged, but what comes out is an uneasy laugh. ‘Don’t you ever hold back? Bite your tongue?’

‘Often,’ says Zoya. ‘More than you know.’

Rachel sips her tea. It tastes of sticks. ‘Well, you don’t know everything. I can’t think about the future in Kiev. I need to go home, let things settle. Then we will see.’

Zoya snorts. ‘Oh yes. You will see. Already you know what you will see.’

‘He needs me, I think. He wants to make plans. I never expected—’

‘He needs you to know when to go.’

Rachel wonders if anyone else in the café can hear them. She glances around, but the café is nearly empty apart from a young woman sitting by herself at a table near the door, her arms folded, legs crossed, one foot pushing against the base of the table as if she has been waiting just a little too long. Rachel lowers her voice. ‘Well, I didn’t come to talk about Lucas and me. I want to ask you something. Will you keep an eye on Stepan? Look out for him, I mean.’

Now Zoya leans back and stares out of the window. ‘That boy? He knows how to look out for himself, don’t you think?’

Rachel follows her gaze, half expecting to see Stepan’s face pressed against the glass, peering in from the pavement. Instead she sees a kvas truck with one wheel stuck in a pothole. It is blocking a lorry that is trying to turn left across the boulevard. A horn blares but the kvas truck won’t shift. Cars are backing up.

‘Elena really cared about him,’ she says. ‘And he cared about her. He’s just a child. He needs someone to protect him. I should have helped—’

‘So!’ Zoya taps her packet of cigarettes on the table for emphasis. ‘You feel guilty. Well, I don’t. Stepan betrayed Elena. He will do anything for five dollars, or ten. He spied for Mykola Sirko, and,’ she barely hesitates, ‘I will tell you something now – something you need to know. Mykola was telling a lie when he told us what Elena had done – a very big lie. She was not a mother when the Germans invaded. But later she did have a son – Oleksandr – born in 1952. She couldn’t keep him – the father was a local Party boss who caused a problem for the high-ups in Moscow. Well, he was removed. Shot on the street one day not far from here. Probably Elena thought she would be next. Her family did not survive the famine and she had no one else. So Oleksandr grew up in a home for children whose parents are dead.’

‘An orphanage.’ Rachel, as if nodding might help her absorb what she is hearing.

‘An orphanage, yes – across the river. They gave him a new name.’

‘Mykola Sirko…’

‘And when he was a young man Mykola traced his mother. He must have paid a bribe for the information or blackmailed an official, but he never told her who he was. Instead he taunted her. He left cruel messages and rented empty flats for his businesses right under her nose. Then you moved in to the apartment block. Well, Elena did not know what he was saying when he stopped us in the car, but I think he told you that lie to make you hate her.

‘She didn’t guess who he was?’

‘I don’t think so. He was registered at the orphanage when he was six weeks old.’

‘That’s terrible.’ Rachel whispers the words. ‘Do – do you think she killed herself?’

Zoya shrugs.

Rachel presses her free hand across her eyes, shutting off the tears that are forming beneath her lids. Elena’s child did not die in those Nazi murder pits on the edge of the city. Mykola’s lie had been unspeakably cruel.

‘How did you find out?’

‘Elena told me she had a child,’ says Zoya. ‘One afternoon while we were folding sheets. I think the burden was too much. So I started looking. It was difficult, but I know who to ask. And this man was following her. I made the connection that Elena could not. He left horrible things on her doorstep. He tied dogs together to make them bark all night, or paid Stepan to do it for him.’

‘Stepan?’

‘Stop repeating. Yes, Stepan. He does anything for money. He is spy!’ Zoya makes a sour face. ‘Well, I have Elena’s rent money, she left it in a box under her bed, five thousand dollars, and you know what I am going to do with it? I am going to buy a lawyer who will dig up the crimes that Mykola Sirko has done. He does not deserve your pity, you understand?’

‘Shh, Zoya, please…’ Rachel sees a baby in her mind’s eye, falling, falling. Maybe it is Mykola, or maybe another. She blinks. ‘It is Stepan I wanted to talk to you about. Look after him. Elena loved him, like a grandson. We can’t abandon him.’

Now there is a glint of triumph in Zoya’s eye. ‘But you can – you are disappearing! Poor little Snegurochka!’

Rachel’s heart is thumping. She fights back the urge to count the cars, count the passers-by. In three days she will be on a plane. In four days she will visit her own mother, still the same daughter, now with different knowledge inside her. She takes a breath. ‘Sometimes you say I have no business being here; then you say I am wrong to leave. Well, I didn’t ask for things to happen, but there are consequences, they pile up even when I do nothing. And if I ask for your help, that’s something, isn’t it? It’s not everything. I am leaving. But it’s something.’

Zoya turns her head and looks out of the window. She is frowning, as usual, and in the glare of sunlight Rachel sees a woman who might be thirty, or fifty, with dark roots showing through her bleached yellow hair.

‘I won’t give him Elena’s money,’ says Zoya.

‘That’s not what I meant—’

‘So you might as well know. Stepan is already sleeping at my flat. In my grandfather’s bed.’ Zoya covers her mouth with her hand, but her glistening eyes betray her. ‘The little rat tells me it smells of piss. Ha! I tell him it is better than the other.’

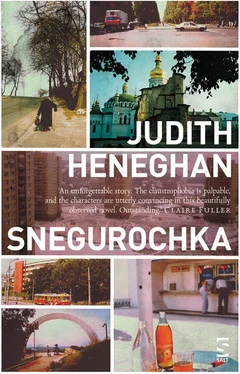

THE DAY BEFORE Lucas and Rachel are due to leave Kiev, Rachel goes for a walk. It is the first day of September, a Sunday. The summer has been hot and dry since the early rain in June; already the horse chestnut leaves are starting to curl at the edges. There is a tang in the air, almost acidic – a whisper of coolness. Ivan doesn’t want to be in the pushchair, but it is after lunch and he will sleep soon – precious time she ought to use for packing. She isn’t ready to leave, though. Not until she has taken one last stroll. The pavements and footpaths are woven through her now, their circuitous routes bound to her nerve-endings.

Rachel pauses at one of the new craft stalls outside the monastery. The table is laden with wooden toys, some brightly painted and gleaming in the afternoon sunshine. Others are plain, cheaper, the do-it-yourself variety of stacking dolls – one for papa, one for mama, one for baby, or two or three. She is tempted by a bell-shaped figure with intricate gold and blue patterns on its skirt that tinkles when she lifts it.

Читать дальше