Kenny sat in the front seat, just like he did in the airplane. As they drove out of the parking lot, his father asked him about his dark glasses.

“Mr. Garcia gave them to me,” Kenny said.

Kenny told his father about aiming for Mount Shasta, then about going to the zoo and the peewee golf and seeing the old house.

“Ah,” his father said. He said it again when Kenny told him the Callendars had moved away.

As they rode into town and back to the Blue Gum Restaurant, Kenny looked out the window, his eyes tinted a deep blue by his metal-framed sunglasses, scanning the sky. Mr. Garcia had probably taken off by now, and Kenny hoped to see the plane up there. His mom would be sitting in the copilot’s seat.

But there was no sign of them. None at all.

These Are the Meditations of My Heart

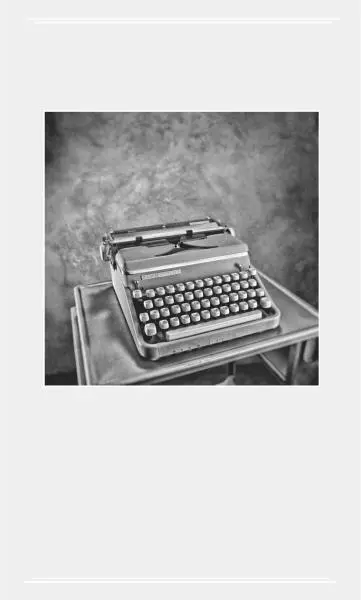

She was not looking to buy an old typewriter. She needed nothing and wanted no more possessions—new, used, antique—not a thing. She had vowed to weather her recent personal setbacks with an era of Spartan living; a new minimalism, a life she could fit in her car.

She liked her small apartment west of the Cuyahoga River. She’d tossed away all the clothes she’d worn with him, the Knothead; she cooked for herself almost every night and listened to a lot of podcasts. She had enough money saved to see her to the New Year, allowing a lazy, agenda-free summer. January would freeze the lake and probably burst the pipes of her building, but by then she would be gone. New York or Atlanta or Austin or New Orleans. She had options galore as long as she traveled light. But the Lakewood Methodist Church on the corner of Michigan and Sycamore was having a Saturday Parking Lot Sale, raising money for community service programs like Free Day Care, twelve-step program meetings, and, she didn’t know, maybe Meals on Wheels. She was neither a churchgoer nor a baptized Methodist, but she was fairly certain that sauntering through a parking lot full of card tables brimming with yard sale debris was not an act of worship.

As a hoot she almost bought a set of aluminum TV dinner trays, but three of them showed signs of rust. Boxes of costume jewelry revealed no treasures. But then she saw a set of Tupperware ice pop makers. As a kid, she had been in charge of pouring Kool-Aid or orange juice into the molds and inserting the patented plastic handles, which, when the freezer had done the physics, made for inexpensive icy treats. She could almost feel the hot wind of summer in the foothills, her hands sticky from melting, fruity ice. With no haggling, she got the set for a dollar.

On the same table was the typewriter, the color of faded Pop Art red—not an attraction. What got her eye was the adhesive label glued to the top left corner of its housing. In lowercase letters and underlined (by using the Shift and 6 key) the original owner had typed

The words had been typed as many as thirty years ago, when the machine was brand new, just out of the box, perhaps a gift on a girl’s thirteenth birthday. A more recent owner had typed BUY ME FOR $5 on a piece of paper and rolled it into the carriage.

The machine was a portable; the body was plastic. The ribbon was two-tone, black over red, and there was a hole in the lid where the name Smith Corona or Brother or Olivetti had once been plugged. There was also a reddish leatherette carrying case with a half-sleeve opening and push-button latch. She punched three of the keys—A, F, P—and they all clacked onto the paper and settled back again. So, the thing worked, sort of.

“Is this typewriter really only five dollars?” she asked of a Lady Methodist at a nearby card table.

“That?” the woman said. “I think it works but nobody uses typewriters anymore.”

That was not the question she had asked, but she didn’t care. “I’ll take it.”

“Show me the money.”

And just like that the Methodists were five bucks richer.

—

At her apartment, she prepped a supply of pineapple juice ice pops for later that night. She’d have a couple when the day cooled, when she could have her windows open and watch for the first fireflies of the evening. She pulled the typewriter from its cheap case, set it out on her tiny kitchen table, and rolled in a piece of printer paper from the feed of her LaserWriter. She tried each of the keys—many stuck. One of the four rubber feet on the bottom of the body was missing, so the machine rocked a bit. She pounded each of the keys from the top row straight across, shifting to caps as well, trying, with some degree of success, to shake loose the stickiness. Though the ribbon was old, the letters were legible. She tried the spacing of the carriage return—single and double—which worked, although the bell did not. The margin sliders scraped and then jammed in place.

The typewriter needed a firm scrubbing and a lube job, which she expected to run, say, twenty-five dollars. But she pondered the greater conundrum, one that faces all who buy a typewriter in the third millennium: what is its purpose? Addressing envelopes. Her mom would enjoy typewritten letters from her wandering daughter. She could send poison-pen messages to her ex, like, “Hey, Knothead, you made a big fucking mistake!” with no fear of an email record. She could type out some remark, take a digital photo of it with her phone, then post that onto her blog and Facebook page. She could make to-do lists for the refrigerator door. That made for five Hipster-Retro reasons for her to own a new-old typewriter. Chuck in a few heartfelt meditations and she had six valid uses.

She typed the original owner’s intent for the machine.

The space bar skipped, which would not do. She grabbed her phone and googled old typewriter repair .

Three listings gave her the choices of a shop two hours away near Ashtabula, a place downtown that did not answer its phone, or, crazily enough, Detroit Avenue Business Machines, which was just a few minutes’ walk away. She knew the shop—it was next to a tire store. She had strolled past it many times on her way to a great pizzeria and, a few doors down, to the art supply store that was soon to go out of business. She thought the small shop was for computers and printer repair so, after taking the few-minutes’ walk, was amused to see, upon closer inspection of its front window, an old adding machine, a thirty-year-old telephone answering machine, something called a Dictaphone, and an ancient typewriter. The bell over the door tinkled when she entered.

One side of the shop was nothing but printers—boxes of them along with toner cartridges for any model. The other side of the shop was like a Museum for Yesteryear’s Tools of Commerce. There were adding machines with eighty-one keys and pull handles, single-use ten-key calculators, a stenographer’s machine, IBM Selectric typewriters, most in beige housings, and, on wall-mounted shelves, dozens of assorted typewriters gleaming black, red, green, even baby blue. They all appeared to be in perfect working order.

The service counter was in the rear of the shop. Behind it were desks and a workbench, where an old fellow was going over papers.

“How can I help the young lady?” he asked with a slight accent, most likely Polish.

Читать дальше