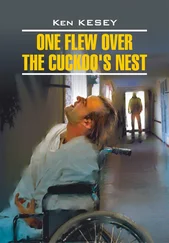

“I’m from the Columbia Gorge,” I said, and he waited for me to go on. “My Papa was a full Chief and his name was Tee Ah Millatoona. That means The-Pine-That-Stands-Tallest-on-the-Mountain, and we didn’t live on a mountain. He was real big when I was a kid. My mother got twice his size.”

“You must of had a real moose of an old lady. How big was she?”

“Oh — big, big.”

“I mean how many feet and inches?”

“Feet and inches? A guy at the carnival looked her over and says five feet nine and weight a hundred and thirty pounds, but that was because he’d just saw her. She got bigger all the time.’”

“Yeah? How much bigger?”

“Bigger than Papa and me together.”

“Just one day took to growin’, huh? Well, that’s a new one on me: I never heard of an Indian woman doing something like that.”

“She wasn’t Indian. She was a town woman from The Dalles.”

“And her name was what? Bromden? Yeah, I see, wait a minute.” He thinks for a while and says, “And when a town woman marries an Indian that’s marryin’ somebody beneath her, ain’t it? Yeah, I think I see.”

“No. It wasn’t just her that made him little. Everybody worked on him because he was big, and wouldn’t give in, and did like he pleased. Everybody worked on him just the way they’re working on you.”

“They who, Chief?” he asked in a soft voice, suddenly serious.

“The Combine. It worked on him for years. He was big enough to fight it for a while. It wanted us to live in inspected houses. It wanted to take the falls. It was even in the tribe, and they worked on him. In the town they beat him up in the alleys and cut his hair short once. Oh, the Combine’s big — big. He fought it a long time till my mother made him too little to fight any more and he gave up.”

McMurphy didn’t say anything for a long time after that. Then he raised up on his elbow and looked at me again, and asked why they beat him up in the alleys, and I told him that they wanted to make him see what he had in store for him only worse if he didn’t sign the papers giving everything to the government.

“What did they want him to give to the government?”

“Everything. The tribe, the village, the falls…”

“Now I remember; you’re talking about the falls where the Indians used to spear salmon — long time ago. Yeah. But the way I remember it the tribe got paid some huge amount.”

“That’s what they said to him. He said, What can you pay for the way a man lives? He said, What can you pay for what a man is? They didn’t understand. Not even the tribe. They stood out in front of our door all holding those checks and they wanted him to tell them what to do now. They kept asking him to invest for them, or tell them where to go, or to buy a farm. But he was too little anymore. And he was too drunk, too. The Combine had whipped him. It beats everybody. It’ll beat you too. They can’t have somebody as big as Papa running around unless he’s one of them. You can see that.”

“Yeah, I reckon I can.”

“That’s why you shouldn’t of broke that window. They see you’re big, now. Now they got to bust you.”

“Like bustin’ a mustang, huh?”

“No. No, listen. They don’t bust you that way; they work on you ways you can’t fight! They put things in! They install things. They start as quick as they see you’re gonna be big and go to working and installing their filthy machinery when you’re little, and keep on and on and on till you’re fixed!”

“Take ‘er easy, buddy; shhh.”

“And if you fight they lock you someplace and make you stop—”

“Easy, easy, Chief. Just cool it for a while. They heard you.” He lay down and kept still. My bed was hot, I noticed. I could hear the squeak of rubber soles as the black boy came in with a flashlight to see what the noise was. We lay still till he left.

“He finally just drank,” I whispered. I didn’t seem to be able to stop talking, not till I finished telling what I thought was all of it. “And the last I see him he’s blind in the cedars from drinking and every time I see him put the bottle to his mouth he don’t suck out of it, it sucks out of him until he’s shrunk so wrinkled and yellow even the dogs don’t know him, and we had to cart him out of the cedars, in a pickup, to a place in Portland, to die. I’m not saying they kill. They didn’t kill him. They did something else.”

I was feeling awfully sleepy. I didn’t want to talk any more. I tried to think back on what I’d been saying, and it didn’t seem like what I’d wanted to say.

“I been talking crazy, ain’t I?”

“Yeah, Chief” — he rolled over in his bed — “you been talkin’ crazy.”

“It wasn’t what I wanted to say. I can’t say it all. It don’t make sense.”

“I didn’t say it didn’t make sense, Chief, I just said it was talkin’ crazy.”

He didn’t say anything after that for so long I thought he’d gone to sleep. I wished I’d told him good night. I looked over at him, and he was turned away from me. His arm wasn’t under the covers, and I could just make out the aces and eights tattooed there. It’s big, I thought, big as my arms used to be when I played football. I wanted to reach over and touch the place where he was tattooed, to see if he was still alive. He’s layin’ awful quiet, I told myself, I ought to touch him to see if he’s still alive. …

That’s a lie. I know he’s still alive. That ain’t the reason I want to touch him.

I want to touch him because he’s a man.

That’s a lie too. There’s other men around. I could touch them.

I want to touch him because I’m one of these queers!

But that’s a lie too. That’s one fear hiding behind another. If I was one of these queers I’d want to do other things with him. I just want to touch him because he’s who he is.

But as I was about to reach over to that arm he said, “Say, Chief,” and rolled in bed with a lurch of covers, facing me, “Say, Chief, why don’t you come on this fishin’ trip with us tomorrow?”

I didn’t answer.

“Come on, what do ya say? I look for it to be one hell of an occasion. You know these two aunts of mine comin’ to pick us up? Why, those ain’t aunts, man, no; both those girls are workin’ shimmy dancers and hustlers I know from Portland. What do you say to that?”

I finally told him I was one of the Indigents.

“You’re what?”

“I’m broke.”

“Oh,” he said. “Yeah, I hadn’t thought of that.”

He was quiet for a time again, rubbing that scar on his nose with his finger. The finger stopped. He raised up on his elbow and looked at me.

“Chief,” he said slowly, looking me over, “when you were full-sized, when you used to be, let’s say, six seven or eight and weighed two eighty or so — were you strong enough to, say, lift something the size of that control panel in the tub room?”

I thought about that panel. It probably didn’t weigh a lot more’n oil drums I’d lifted in the Army. I told him I probably could of at one time.

“If you got that big again, could you still lift it?”

I told him I thought so.

“To hell with what you think; I want to know can you promise to lift it if I get you big as you used to be? You promise me that, and you not only get my special body-buildin’ course for nothing but you get yourself a ten-buck fishin’ trip, free!” He licked his lips and lay back. “Get me good odds too, I bet.”

He lay there chuckling over some thought of his own. When I asked him how he was going to get me big again he shushed me with a finger to his lips.

“Man, we can’t let a secret like this out. I didn’t say I’d tell you how , did I? Hoo boy, blowin’ a man back up to full size is a secret you can’t share with everybody, be dangerous in the hands of an enemy. You won’t even know it’s happening most of the time yourself. But I give you my solemn word, you follow my training program, and here’s what’ll happen.”

Читать дальше