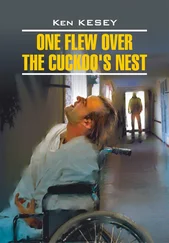

The group isn’t saying. They know whose play it is next. She folds Harding’s folio back up and puts it on her lap and crosses her hands over it, looking around the room just like somebody might dare have something to say. When it’s clear nobody’s going to talk till she does, her head turns again to the doctor. “It sounds like a fine plan, Doctor Spivey, and I appreciate Mr. McMurphy’s interest in the other patients, but I’m terribly afraid we don’t have the personnel to cover a second day room.”

And is so certain that this should be the end of it she starts to open the folio again. But the doctor has thought this through more than she figured.

“I thought of that too, Miss Ratched. But since it will be largely the Chronic patients who remain here in the day room with the speaker — most of whom are restricted to lounges or wheel chairs — one aide and one nurse in here should easily be able to put down any riots or uprisings that might occur, don’t you think?”

She doesn’t answer, and she doesn’t care much for his joking about riots and uprisings either, but her face doesn’t change. The smile stays.

“So the other two aides and nurses can cover the men in the tub room, perhaps even better than here in a larger area. What do you think, men? Is it a workable idea? I’m rather enthused about it myself, and I say we give it a try, see what it’s like for a few days. If it doesn’t work, well, we’ve still got the key to lock it back up, haven’t we?”

“Right!” Cheswick says, socks his fist into his palm. He’s still standing, like he’s afraid to get near that thumb of McMurphy’s again. “Right, Doctor Spivey, if it don’t work, we’ve still got the key to lock it back up. You bet.”

The doctor looks around the room and sees all the other Acutes nodding and smiling and looking so pleased with what he takes to be him and his idea that he blushes like Billy Bibbit and has to polish his glasses a time or two before he can go on. It tickles me to see the little man so happy with himself. He looks at all the guys nodding, and nods himself and says, “Fine, fine,” and settles his hands on his knees. “Very good. Now. If that’s decided — I seem to have forgotten what we were planning to talk about this morning?”

The nurse’s head gives that one little jerk again, and she bends over her basket, picks up a folio. She fumbles with the papers, and it looks like her hands are shaking. She draws out a paper, but once more, before she can start reading out of-it, McMurphy is standing and holding up his hand and shifting from foot to foot, giving a long, thoughtful, “Saaaay,” and her fumbling stops, freezes as though the sound of his voice froze her just like her voice froze that black boy this morning. I get that giddy feeling inside me again when she freezes. I watch her close while McMurphy talks.

“Saaaaay, Doctor, what I been dyin’ to know is what did this dream I dreamt the other night mean? You see, it was like I was me , in the dream, and then again kind of like I wasn’t me — like I was somebody else that looked like me — like — like my daddy! Yeah, that’s who it was. It was my daddy because sometimes when I saw me — him — I saw there was this iron bolt through the jawbone like daddy used to have—”

“Your father has an iron bolt through his jawbone?”

“Well, not any more, but he did once when I was a kid. He went around for about ten months with this big metal bolt going in here and coming out here! God, he was a regular Frankenstein. He’d been clipped on the jaw with a pole ax when he got into some kinda hassle with this pond man at the logging mill — Hey! Let me tell you how that incident came about. …”

Her face is still calm, as though she had a cast made and painted to just the look she wants. Confident, patient, and unruffled. No more little jerk, just that terrible cold face, a calm smile stamped out of red plastic; a clean, smooth forehead, not a line in it to show weakness or worry; flat, wide, painted-on green eyes, painted on with an expression that says I can wait, I might lose a yard now and then but I can wait, and be patient and calm and confident, because I know there’s no real losing for me.

I thought for a minute there I saw her whipped. Maybe I did. But I see now that it don’t make any difference. One by one the patients are sneaking looks at her to see how she’s taking the way McMurphy is dominating the meeting, and they see the same thing. She’s too big to be beaten. She covers one whole side of the room like a Jap statue. There’s no moving her and no help against her. She’s lost a little battle here today, but it’s a minor battle in a big war that she’s been winning and that she’ll go on winning. We mustn’t let McMurphy get our hopes up any different, lure us into making some kind of dumb play. She’ll go on winning, just like the Combine, because she has all the power of the Combine behind her. She don’t lose on her losses, but she wins on ours. To beat her you don’t have to whip her two out of three or three out of five, but every time you meet. As soon as you let down your guard, as soon as you lose once , she’s won for good. And eventually we all got to lose. Nobody can help that.

Right now, she’s got the fog machine switched on, and it’s rolling in so fast I can’t see a thing but her face, rolling in thicker and thicker, and I feel as hopeless and dead as I felt happy a minute ago, when she gave that little jerk — even more hopeless than ever before, on account of I know now there is no real help against her or her Combine. McMurphy can’t help any more than I could. Nobody can help. And the more I think about how nothing can be helped, the faster the fog rolls in.

And I’m glad when it gets thick enough you’re lost in it and can let go, and be safe again.

There’s a Monopoly game going on in the day room. They’ve been at it for three days, houses and hotels everywhere, two tables pushed together to take care of all the deeds and stacks of play money. McMurphy talked them into making the game interesting by paying a penny for every play dollar the bank issues them; the monopoly box is loaded with change.

“It’s your roll, Cheswick.”

“Hold it a minute before he rolls. What’s a man need to buy thum hotels?”

“You need four houses on every lot of the same color, Martini. Now let’s go , for Christsakes.”

“Hold it a minute.”

There’s a flurry of money from that side of the table, red and green and yellow bills blowing in every direction.

“You buying a hotel or you playing happy new year, for Christsakes?”

“It’s your dirty roll, Cheswick.”

“Snake eyes! Hoooeee, Cheswicker, where does that put you? That don’t put you on my Marvin Gardens by any chance? That don’t mean you have to pay me, let’s see, three hundred and fifty dollars?”

“Boogered.”

“What’s thum other things? Hold it a minute. What’s thum other things all over the board?”

“Martini, you been seeing them other things all over the board for two days. No wonder I’m losing my ass. McMurphy, I don’t see how you can concentrate with Martini sitting there hallucinating a mile a minute.”

“Cheswick, you never mind about Martini. He’s doing real good. You just come on with that three fifty, and Martini will take care of himself; don’t we get rent from him every time one of his ‘things’ lands on our property?”

“Hold it a minute. There’s so many of thum.”

“That’s okay, Mart. You just keep us posted whose property they land on. You’re still the man with the dice, Cheswick. You rolled a double, so you roll again. Atta boy. Faw! a big six.”

Читать дальше