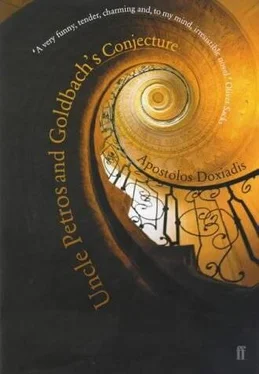

Apostolos Doxiadis - Uncle Petros and Goldbach

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Apostolos Doxiadis - Uncle Petros and Goldbach» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Uncle Petros and Goldbach

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Uncle Petros and Goldbach: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Uncle Petros and Goldbach»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

"Every family has its black sheep-in ours it was Uncle Petros": the narrator of Apostles Doxiadis's novel Uncle Petros and Goldbach's Conjecture is the mystified nephew of the family's black sheep, unable to understand the reasons for his uncle's fall from grace. A kindly, gentle recluse devoted only to gardening and chess, Petros Papachristos exhibits no signs of dissolution or indolence: so why do his family hold him in such low esteem? One day, his father reveals all:

Your uncle, my son, committed the greatest of sins… he took something holy and sacred and great, and shamelessly defiled it! The great, unique gift that God had blessed him with, his phenomenal, unprecedented mathematical talent! The miserable fool wasted it; he squandered it and threw it out with the garbage. Can you imagine it? The ungrateful bastard never did one day's useful work in mathematics. Never! Nothing! Zero!

Instead of being warned off, the nephew instead has his curiosity provoked, and what he eventually discovers is a story of obsession and frustration, of Uncle Petros's attempts at finding a proof for one of the great unsolved problems of mathematics-Goldbach's conjecture.

If this might initially seem undramatic material for a novel, readers of Fermat's Last Theorem, Simon Singh's gripping true-life account of Andrew Wiles's search for a proof for another of the great long-standing problems of mathematics, would surely disagree. What Doxiadis gives us is the fictional corollary of Singh's book: a beautifully imagined narrative that is both compelling as a story and highly revealing of a rarefied world of the intellect that few people will ever access. Without ever alienating the reader, he demonstrates the enchantments of mathematics as well as the ambition, envy and search for glory that permeate even this most abstract of pursuits. Balancing the narrator's own awkward move into adulthood with the painful memories of his brilliant uncle, Doxiadis shows how seductive the world of numbers can be, and how cruel a mistress. "Mathematicians are born, not made," Petros declares: an inheritance that proves to be both a curse and a gift.-Burhan Tufail

Review

If you enjoyed Fermat's Last Theorem, you'll devour this. However, you don't need to be an academic to understand its imaginative exploration of the allure and danger of genius. Old Uncle Petros is a failure. The black sheep of a wealthy Greek family, he lives as a recluse surrounded by dusty books in an Athenian suburb. It takes his talented nephew to penetrate his rich inner world and discover that this broken man was once a mathematical prodigy, a golden youth whose ambition was to solve one of pure maths' most famous unproven hypotheses – Goldbach's Conjecture. Fascinated, the young man sets out to discover what Uncle Petros found – and what he was forced to sacrifice. Himself a mathematician as well as a novelist, Doxiadis succeeds in shining a light into the spectral world of abstract number theory where unimaginable concepts and bizarre realities glitter with a cold, magical and ultimately destructive beauty. (Kirkus UK)