Harkoo, Deasey said, was a Village eccentric of long standing, connected to the founders of one of the posh Fifth Avenue department stores. He was a widower-twice over-who lived in a queer house with a daughter from his first marriage. In addition to looking after the day-to-day affairs of his gallery, orchestrating his disputes with fellow members of the American Communist Party, and pulling off his celebrated fetes, he was also, in idle moments, writing a largely unpunctuated novel, already more than a thousand pages long, which described, in cellular detail, the process of his own birth. He had taken his unlikely name in the summer of 1924, while sharing a house at La Baule with Andre Breton, when a pale, hugely endowed figure calling himself the Long Man of Harkoo recurred five nights running in his dreams.

"Right here," Deasey called out to the driver, and the cab came to a stop in front of a row of indistinct modern apartment blocks. "Pay the fare, will you, Clay? I'm a little short."

Sammy scowled at Joe, who considered that his cousin really ought to have expected this. Deasey was a classic cadger of a certain type, at once offhand and peremptory. But Joe had discovered that Sammy was, in his own way, a classic tightwad. The entire concept of taxicabs seemed to strike Sammy as recherche and decadent, on a par with the eating of songbirds. Joe took a dollar from his wallet and passed it to the driver.

"Keep the change," he said.

The Harkoo house lay entirely hidden from the avenue, "like an emblem (heavy-handed at that) of suppressed nasty urges," as Auden put it in his letter to Isherwood, at the heart of a city block the whole of which subsequently passed into the hands of New York University, was razed, and now forms the site of the massive Levine School of Applied Meteorology. The solid rampart of row houses and apartment blocks that enclosed the Harkoo house and its grounds on all four sides could be breached only by way of a narrow ruelle that slipped unnoticed between two buildings and penetrated, through a tunnel of ailanthus trees, to the dark, leafy yard within.

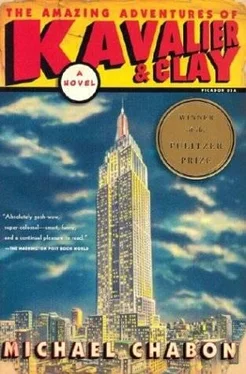

The house, when they reached it, was a vest-pocket Oriental fantasy, a miniature Topkapi, hardly bigger than a firehouse, squeezed onto its tiny site. It curled like a sleeping cat around a central tower topped witha dome that resembled, among other items, a knob of garlic. Through skillful use of forced perspective and manipulation of scale, the house managed to look much bigger than it really was. Its luxurious coat of Virginia creeper, the gloom of its courtyard, and the artless jumble of its gables and spires gave the place an antique air, but it had in fact been completed in September 1930, around the time that Al Smith was laying the cornerstone for the Empire State Building. Like that structure, it was a kind of dream habitation, having, like the Long Man of Harkoo himself, originally appeared to Longman Harkoo in his sleep, giving him the excuse he had long sought to pull down the dull old Greek Revival house that had been the country home of his mother's family since the founding of Greenwich Village. That house had itself replaced a much earlier structure, dating to the first years of British dominion, in which-or so Harkoo claimed-a Dutch-Jewish forebear of his had entertained the devil during his 1682 tour of the colonies.

Joe noticed that Sammy was hanging back a little, looking up at the miniature tower, absently massaging the top of his left thigh, his face solemn and nervous in the light of the torches that flanked the door. In his gleaming pinstriped suit, he reminded Joe of their character the Monitor, armored for battle against perfidious foes. Suddenly Joe felt apprehensive, too. It had not quite sunk in until now, with all the talk of bombs and woolens and radio programs, that they had come downtown with Deasey to attend a party.

Neither of the cousins was much for parties. Though Sammy was mad for swing, he could not, of course, dance on his pipe-cleaner legs; his nerves killed his appetite, and at any rate, he was too self-conscious about his manners to eat anything; and he disliked the flavor of liquors and beer. Introduced into a cursed circle of jabber and jazz, he would drift helplessly behind a large plant. His brash and heedless gift of conversation, by means of which he had whipped up Amazing Midget Radio Comics and with it the whole idea of Empire, deserted him. Put him in front of a roomful of people at work and he would be impossible to shut up; work was not work for him. Parties were work. Women were work. At Palooka Studios, whenever there occurred the chance conjunction of girls and a bottle, Sammy simply vanished, like Mike Campbell's fortune, at first a little at a time, and then all at once.

Joe, on the other hand, had always been the boy for a party in Prague. He could do card tricks and hold his alcohol; he was an excellent dancer. In New York, however, all this seemed to have changed. He had too much work to do, and parties seemed a great waste of his time. The conversation came fast and slangy, and he had trouble following the gags and patter of the men and the sly double-talk of the ladies. He was vain enough to dislike it when something he said in all seriousness for some reason broke up a room. But the greatest obstacle he faced was that he did not feel that he ought-ever-to be enjoying himself socially. Even when he went to the movies, he did so in a purely professional capacity, studying them for ideas about light and imagery and pacing that he could borrow or adapt in his comic book work. Now he drew back alongside his cousin, looking up at the scowling torchlit face of the house, ready to run at the first signal from Sam.

"Mr. Deasey," Sammy said, "listen. I feel I've got to confess… I haven't even started Strange Frigate yet. Don't you think I better-"

"Yes," Joe said. "And I have the cover for The Monitor -"

"All you need is a drink, boys." Deasey looked greatly amused by their sudden qualms of conscience and courage. "That will make it go much easier when they pitch you both into the volcano. I presume you are virgins?" They scraped up the rough, clinker-brick front steps. Deasey turned, and all at once his face looked grave and admonitory. "Just don't let him hug you," he said.

The party had originally been planned for the pint-sized mansion's ballroom, but when that room was rendered uninhabitable by the noise from Salvador Dali's breathing apparatus, everyone crowded into the library instead. Like all the rooms in the house, the library was diminutive, built to a three-quarter scale that gave visitors a disquieting sense of giantism. Sammy and Joe squeezed in behind Deasey to find the room packed to the point of immobility with Transcendental Symbolists, Purists, and Vitalists, copywriters in suits the color of new Studebakers, socialist banjo players, writers for Mademoiselle, experts on Yuggogheny cannibal cults and bird-worshipers of the Indochinese Highlands, composers of twelve-tone requiems and of slogans for Eas-O-Cran, the Original New England Laxative. The gramophone-and (of course) the bar-had been carried up to the library as well, and over the heads of the crammed-together guests there veered the notes of an Armstrong trumpet solo. Beneath this bright glaze of jazz and a frothy layer of conversation there was a low, heavy rumbling from the distant air compressor. Along with the smells of perfume and cigarettes, the air in the room had a faint motor-oil smell of the wharves.

"Hello, George." Harkoo fought his way toward them, a round, broad, not at all long man, with thinning coppery hair cropped close. "I was hoping you would show."

"Hello, Siggy." Deasey stiffened and offered his hand in a way that struck Joe as defensive or even protective, and then, in the next instant, the man he called Siggy had put a wrestling hold on him, in which seemed to be mingled affection and a desire to snap bones.

Читать дальше