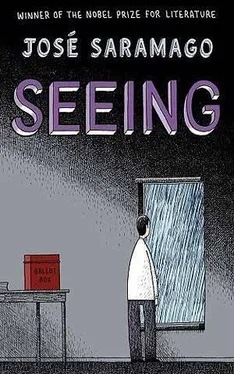

Jose Saramago - Seeing

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jose Saramago - Seeing» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Seeing

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Seeing: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Seeing»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

It's hard not to gallop through prose that uses commas instead of full stops, but once I learned to slow down, the rewards piled up: his sound, sweet humour, his startling imagination, his admirable dogs and lovers, the subtle, honest workings of his mind. Here indeed was a novelist worthy of a reader's trust. So at last I could read his great book – or his greatest until its sequel.

Accepting his Nobel prize, Saramago, calling himself "the apprentice", said: "The apprentice thought, 'we are blind', and he sat down and wrote Blindness to remind those who might read it that we pervert reason when we humiliate life, that human dignity is insulted every day by the powerful of our world, that the universal lie has replaced the plural truths, that man stopped respecting himself when he lost the respect due to his fellow-creatures."

This, on the face of it, is an odd description of Blindness, for in that book it is powerless people who insult human dignity – ordinary people, terrified at finding themselves and everyone else blind, everything out of control. Some behave with stupid, selfish brutality, sauve qui peut. The group of men who seize power in an asylum and use and abuse the weaker inmates have indeed abandoned self-respect and human decency: they are a microcosm of the corruption of power. But the truly powerful of our world don't even appear in Blindness. Seeing is all about them: the perverters of reason, the universal liars. It is about government gone wrong.

Very evidently Saramago's novels are not simple parables. It would be rash to "explain" what all the people (but one) in the first book were blind to, or what it is that the citizens of Seeing see. What's clear is that they're the same people, it's the same city, a few years later: one book illuminates the other in ways I can only begin to glimpse.

The story begins with those ordinary citizens, who not so long ago regained their sight and their tranquil day-to-day lives, doing something that seems quite unconnected with vision or lack of it. It is voting day, and 83% of them, after not going to the polls at all in the morning, go in the late afternoon and cast a blank ballot.

We see the dismay of bureaucrats, the excitement of journalists, the hysteria of the government, and the mild non-response of the citizens, who, when asked how they voted, refuse to say, reminding the questioner that the question is illegal. The satire is at first quite funny, and I thought it was going to be a light, Voltairean tale.

Turning in a blank ballot is a signal unfamiliar to most Britons and Americans, who aren't yet used to living under a government that has made voting meaningless. In a functioning democracy, one can consider not voting a lazy protest liable to play into the hands of the party in power (as when low Labour turn-out allowed Margaret Thatcher's re-elections, and Democratic apathy secured both elections of George W Bush). It comes hard to me to admit that a vote is not in itself an act of power, and I was at first blind to the point Saramago's non-voting voters are making. I began to see it at last, when the minister of defence announces that what the country is facing is terrorism.

Other ministers oppose him but he gets what he wants – a state of emergency, then the exodus of the government, by night, from the capital city, which is declared to be under siege. A bomb is exploded (by terrorists, of course, as the media report), killing quite a few people. An attempted evacuation of the 17% of voters who marked their ballots ends in failure, as the government forgets to tell the troops blocking all the roads to let the refugees through. The so-called terrorists in the city, still mild and peaceable, help the refugees carry back upstairs all they tried to take with them – the tea service, the silver platter, the painting, grandpa…

The humour is still tender but the tone darkens, tension rises. Characters, individuals, begin to come to the fore – all nameless except a dog, Constant, the dog of tears from Blindness. The ministers jockey horribly for power. A superintendent of police is sent into the city to find the woman who did not go blind when everyone else did four years ago, sought as the link between the "plague of white blindness and the plague of blank ballots". The superintendent becomes our viewpoint and mediator; we begin to see as he begins to see. He brings us to the woman, the gentle light-bearer of the first book. But where that story began with an awful darkness that slowly opened into light, this one goes right down into the dark.

José Saramago will be 84 this year. He has written a novel that says more about the days we are living in than any book I have read. He writes with wit, with heartbreaking dignity, and with the simplicity of a great artist in full control of his art. Let us listen to a true elder of our people, a man of tears, a man of wisdom.

Ursula K Le Guin 's Gifts is published by Orion.